- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Bernard Cohen reviews 'horse' by Ania Walwicz

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Virtuosic performance text, palimpsest of a nineteenth-century Russian folktale, and a merciless and often very funny sectioning of the self, Ania Walwicz’s horse enacts what it names: ‘Polyphony as identity’. The narrative more or less follows the story of The Little Humpbacked Horse by Piotr Jerszow ...

- Book 1 Title: horse

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $24.99 pb, 192 pp, 9781742589893

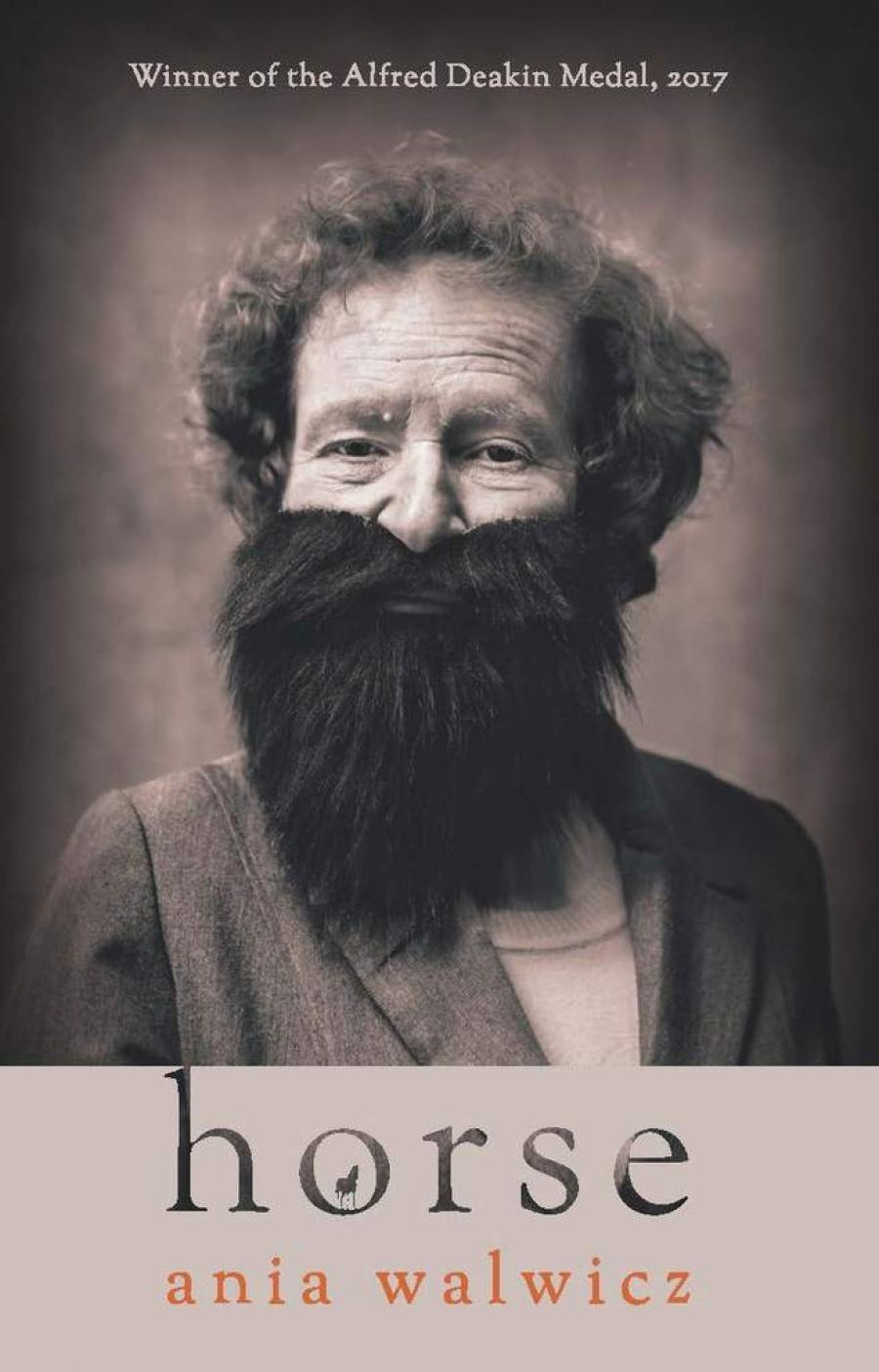

Naomi Herzog’s seriocomic cover photograph shows Walwicz wearing a magnificent beard – the picture is from Herzog’s series of portraits of the writer. (These portraits also provide images for an online performance of sections of horse.) Behind the beard, the authorial persona in horse assembles herself before our eyes from a series of disguises and confessions, pursuits of childhood memories and forgettings, fairy stories, self-discovery within (or, perhaps hyper-identification with) psychoanalytic texts of symptoms, accounts of her professional self (as writer, performer, and teacher) in the world, tall tales of the fabulating heroic or abject self, and whirling, glossolalic wordplay. ‘I am the Russian tsar, old now,’ Walwicz summarises at one point. ‘I am Ivan, Vanya, Ania. I am the princess I want to marry. I am Ivan who brings her over. I am the little magic pony …’

Ania Walwicz (photograph by Naomi Herzog)

Ania Walwicz (photograph by Naomi Herzog)

Walwicz’s previous works, between page and performance, have frequently used a sense of translation or the syntax of the new migrant Other to pull apart the language, logic, and certainty of myths, from ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ (‘I was red, so red so red. I was a tomato. I was on the lookout for the wolf. Want some sweeties, mister?’) to her well-known ‘Australia’: ‘You too far everywhere. You laugh at me. When I came this woman gave me a box of biscuits. You try to be friendly but you’re not very friendly.’

In horse, Walwicz sustains this language play over an extended work. The form of horse – interspersing explanatory and/or framing quotations and references with the more performative passages – doubles as an unusual, engaging, and, on the whole, successful strategy for assisting navigation through the more cut-up aspects of the work. Those passages of shattered Walwiczian narration, with their falling-apart syntax and centrifugal repetitions, are intercut with related, explanatory paragraphs (or even just phrases) from lit-crit and psychoanalytic works, providing an interpretative framework for the reader, adding to and accounting for the textual moves themselves.

As importantly for the book’s subject matter, quotes from and references to psychological texts – from Emil Kraepelin, whose nineteenth-century theories linked bodyweight to disturbance, to Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection, through to gestalt therapist Fritz Perls – track the protagonist’s psychological state. horse contains numerous references to Ania’s (or Ivan Vanya Ania’s or Ania Vanya’s) childhood trauma and its sequelae, from disturbed dreams to eating disorders. The obsessive, performative protagonist of horse is in the grip of compulsive self-diagnosis – she is so intimate with psychoanalytic luminaries, she calls them by their first names: ‘Carl [Jung] says that “the enjoyment of tragedy lies in the thrilling yet satisfying feeling that what is happening to somebody else may very well happen to you”.’

horse is potentially challenging for narrative-seeking readers, with its frequent and inventive disruptions to story structures and the singularity of character. At the risk of extending the intertextual reach of this book, this reviewer found that reading Jerszow’s fairy tale, easily available online, made Walwicz’s narrative sequence seem more concrete. In the fairy tale, the humpbacked horse helps foolish Ivan succeed in a series of quests set by the tsar, including capturing a firebird and abducting the very beautiful Tsar-Maid, whom the tsar decides to marry despite his age and her youth (she is fifteen). As Walwicz crystallises this latter scene:

I am only little now I am 3 or 4 3 or 4 he gives me cakes and cakes now mister love now but I say no to dirty old man now I say no

I say no to the paternal function of symbolic language. I fragment me.

Reciprocally, a footnoted passage quoted from Freud or Jung or Kristeva may be followed with its enactment in the performative or confessional mode. For example, here Freud’s ‘Disturbance of Affect’ segues without even a paragraph break to that distinctive Walwiczian voice:

‘memory … which releases unpleasure … ego discovers this too late. It has permitted a primary process because it did not expect one.’ The symptom becomes physical. I have a dirty mouth. I speak dirty now. I eat cakes and cakes. I go to the cinema. I have to. I wear trousers. I cut short hair. I become a writer.

As noted in horse’s acknowledgments, Walwicz’s work has been anthologised more than two hundred times. Her poetry and performance fix their critiques on everyday and literary mythologies, gain impetus from furious language games and slippages, and establish as natural her characters’ exuberant or anarchic behaviour. In horse, with its focus on the psychological subject, the effect of her work is an often breathlessly compelling blend of humour and discomfort.

Comments powered by CComment