- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

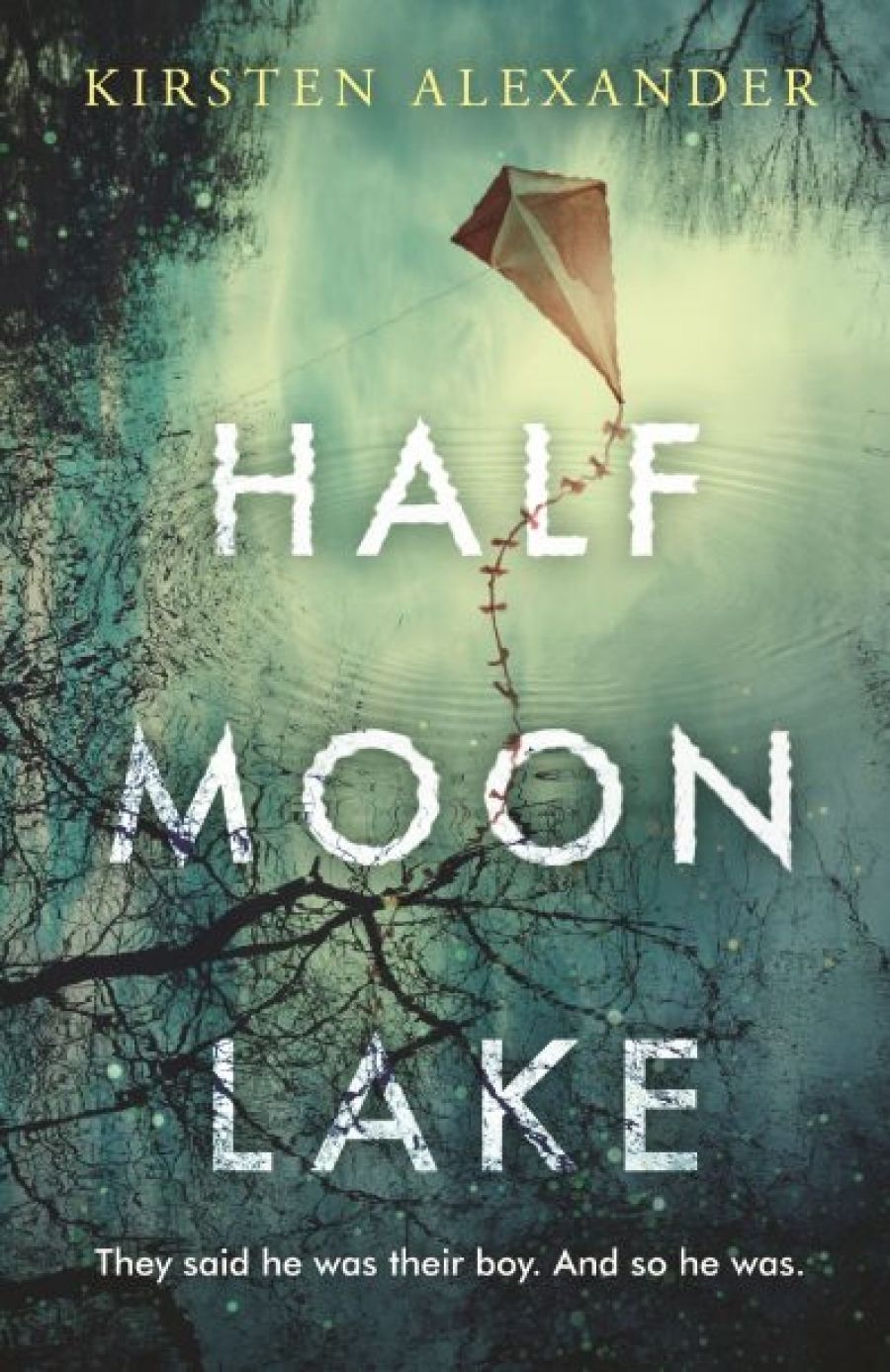

- Custom Article Title: Jane Sullivan reviews 'Half Moon Lake' by Kirsten Alexander

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is it that so fascinates us about lost children? Whether fact or fiction, their stories keep surfacing: Azaria Chamberlain, Jaidyn Leskie, the Beaumont children, or the schoolgirls Joan Lindsay dreamed up for her 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock. Indeed, those girls have wafted through so many subsequent incarnations ...

- Book 1 Title: Half Moon Lake

- Book 1 Biblio: Bantam, $32.99 pb, 336 pp, 9780143792062

The late Peter Pierce wrote a book about this obsession, The Country of Lost Children: An Australian anxiety (1999), in which he examined how the missing child has haunted our imagination. Now Kirsten Alexander has produced an accomplished début novel on this theme.

The place is Opelousas, Louisiana, in 1913, also the setting for the true story that inspired her fiction, the disappearance of Bobby Dunbar. (Spoiler alert: don’t look up this story until you have finished the novel.) Four-year-old Sonny, youngest child of the wealthy Davenport family, walks into the forest around Half Moon Lake on a summer’s day and never returns. Or does he? In this variation on the Lost Child theme, the child is found but is irreparably changed – or perhaps a different child altogether.

After two years, the trail leads to a boy who has been on the road with a tramp. He looks like Sonny, he is about the right age, and has the right distinguishing scar on his arm. And he can’t speak. When Sonny’s mother first sees him, she is confused and overwhelmed: then, suddenly, she declares that he is her boy and the family takes him home.

Some versions of this story, such as the recent The Missing series on SBS, play with the ambiguities – is this the missing child, or an impostor? – in a suspenseful game that goes back to such classics as the sixteenth-century story of Martin Guerre. But there’s no such ambiguity here. The reader already knows the child is not Sonny. The question is: do Sonny’s parents know? And if they do, how will they deal with that knowledge? What follows is a sad and increasingly shocking chain of events, culminating in a court case that had me wanting to shout at everyone involved. The publisher’s blurb on my review copy says the novel is about ‘the parent-child bond, identity, and what it means to be part of a family’. All true: but what the novel is really about is power.

Opelousas in 1913 is a rigidly hierarchical society. This world was built for families like the Davenports: masters of their universe, with the patriarch, John Henry, eager to expand his business empire and enter politics. Then there’s the law, with its own hierarchy: judges, lawyers, sheriffs and their men; plus the media, farmers, workers, and servants; then the strays: tramps and unwed mothers; and the children who toil in the factories. At the very bottom are the Negroes, as they were then called, only recently emancipated.

This suggests a large cast of characters, and Alexander has indeed used recurring points of view from several people up and down the social ladder. Sometimes this feels overcrowded; I would have liked a bit more time to get to know such characters as John Henry or his boys, for example. Wisely, however, Alexander has chosen to focus on two main players: the mothers.

Mary Davenport, Sonny’s mother, is a ready target for our sympathy. She is something of a lost soul herself: her father scorns her, her husband seems unable to console her, and her children recoil from her. People pity her but also consider her a bit mad. Although she is a trapped woman, she clings to the trappings of luxury and status, which define her identity. Everything must stay the same. Alexander is skilful at depicting this weirdly myopic form of melancholy where Mary cannot put a foot right, even when she is trying to be kind. When she gives her Negro servant Esmeralda a cast-off evening gown to pass on to her own daughter, who can never be seen in such finery, ‘Esmeralda walked upstairs to her room, the gown draped dead and damned across one arm.’

While Mary’s grief is muted, Grace Mill’s grief is stark. Mary is elegantly indisposed, Grace vomitously ill. The unmarried farm worker tells everyone the Davenports have her child, and yet she is denied a voice. Even the trial is not about her. She must bury her howls in a pillow, in case anyone hears.

Kirsten Alexander (photograph by Lee Sandwith)

Kirsten Alexander (photograph by Lee Sandwith)

The story builds gradually, but by the second half of the book I was rushing through, desperate to find out if justice would be done. In the courtroom, would a righteous figure like Solomon or Clarence Darrow or Atticus Finch arise to expose the truth? Or would I see Grace and the boy she believes hers reunited by some subversive plan? Or would a key character have a change of heart?

Long before the conclusion, however, the reader is experiencing the anguish of a world made for the powerful, where power inevitably corrupts, with its insidious reach into that supposedly private and sacred space, the family. There are resonances here for all of us, particularly when we think of the Stolen Generations. Evil is done when everyone resolves to look the other way.

Comments powered by CComment