- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: James Walter reviews 'Tiberius with a Telephone: The life and stories of William McMahon' by Patrick Mullins

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Billy McMahon, Australia’s twentieth prime minister, held the post for less than two years (March 1971–December 1972). In surveys of both public esteem and professional opinion, he is generally ranked as our least accomplished prime minister. He is also, until now, the only prime minister for whom there has been no ...

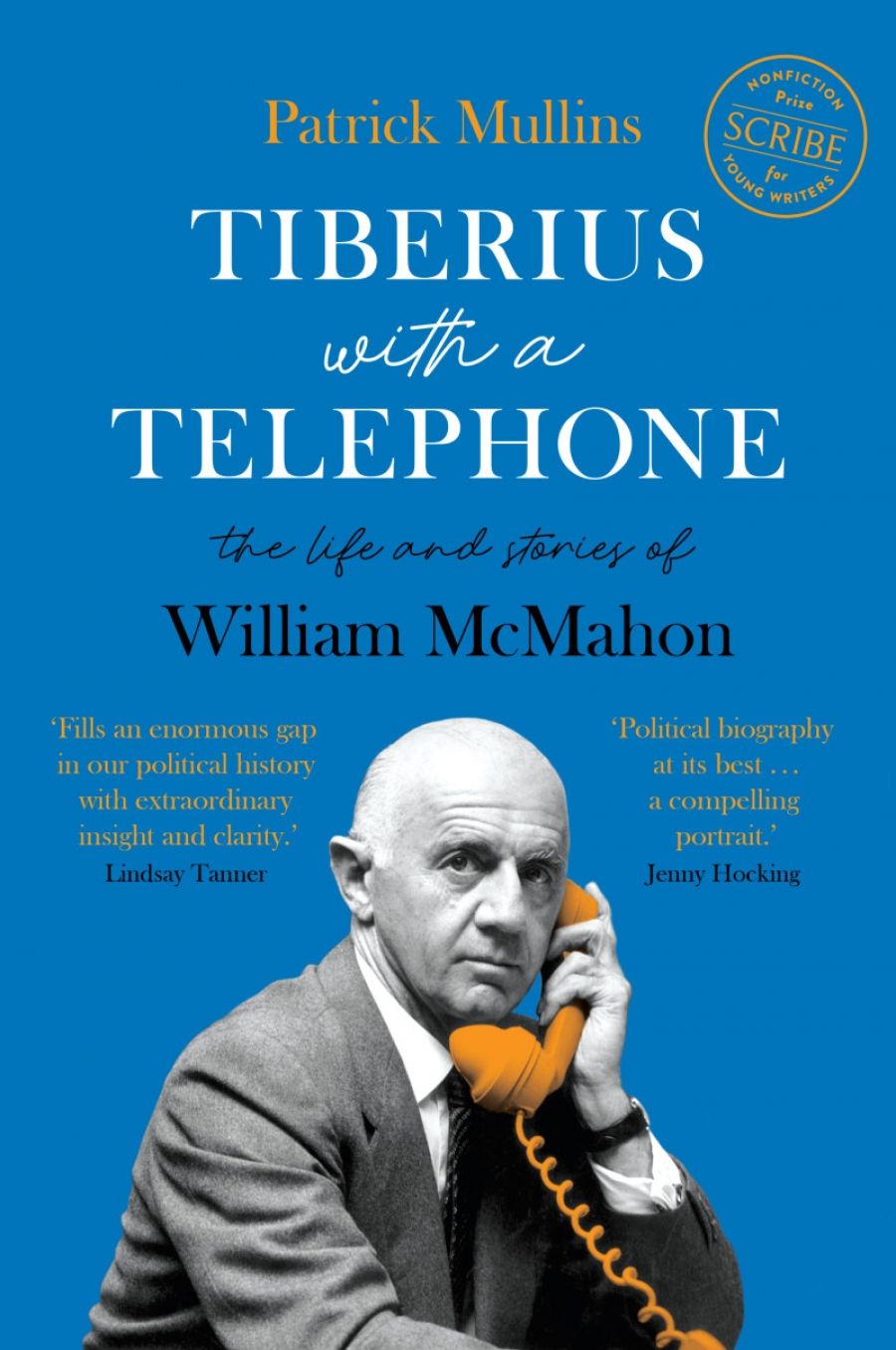

- Book 1 Title: Tiberius with a Telephone: The life and stories of William McMahon

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $59.99 hb, 784 pp, 9781925713602

Patrick Mullins, undeterred, decided there was a purpose in recovering McMahon’s story, found a publisher courageous enough to back the enterprise – to the extent of a near-800-page volume – and succeeds magnificently. This is, as others have remarked, biography at its best: diligently researched, with detail nowhere else examined, and a demonstration of fine judgement concerning the crucial interplay between personal disposition, role demands, and historical context. It illuminates anew the death throes of the Menzies era and the rancorous divisions in the then Coalition government, with considerable relevance for the tribulations of its contemporary successor.

United States President Richard Nixon with Prime Minister McMahon at the White House in 1971 (photograph by Byron E. Schumaker/White House Photo Office)

United States President Richard Nixon with Prime Minister McMahon at the White House in 1971 (photograph by Byron E. Schumaker/White House Photo Office)

Anyone who reads political history or memoir will know Billy McMahon’s fatal flaw: an ambition that led him to extremes in doing whatever was necessary to gain attention and preferment. He was tireless in self-promotion, an incorrigible plotter, a leaker, disloyal and mendacious when it served his purposes, a terrible boss, a wealthy skinflint, and distrustful of others – in short, as Paul Hasluck concluded in a savage assessment, ‘a contemptible creature’. Mullins pulls no punches in assembling even more evidence to substantiate this appraisal.

One might then initially surmise that this is a biography fulfilling one of the principles first canvassed by Plutarch in his Parallel Lives (c.100 ce): that we need ‘bad lives’ better to appreciate the good. Inevitably, the story is more complicated than that, for it contains a mystery to be resolved. How could such a man – despite the adverse opinion of so many, including Robert Menzies himself – continually gain promotion, eventually reaching the pinnacle to which he aspired? The answer is that, though he was never as good as he thought himself to be, he was better and shrewder than his critics appreciated, and appreciably more successful than the impression created by his dithering public persona and assumption of leadership in a government that was already fragmenting, exhausted, and in a dying fall by 1971.

McMahon was arguably the best prepared, certainly the most experienced, of all prime ministers. He had held ministerial office for twenty years before he became leader; was in cabinet continuously between 1956 and 1971; and had served as treasurer. Granted, he assiduously cultivated those who could burnish his image, especially the press proprietor Frank Packer, and traded information and resources when it would advance his cause. However, as Mullins shows us, there was more than public relations, there was substance.

McMahon was a doughty and tenacious combatant for his various portfolios, willing to battle the ‘big beasts’ in cabinet, such as John McEwen, enormously hard-working, and always well-prepared. He was one of the few who tried to dissuade Menzies before his ill-fated engagement in the Suez crisis; he was keen to get out of Vietnam; he fought against protection long before Bob Hawke and Paul Keating were converted to the cause; and he was (as treasurer) ahead of most of the political class in foreseeing the impending failure of the Keynesian compact in the 1970s. Much as he provoked dislike among colleagues, he could not be overlooked. So, over twenty years, he fought his way up the ladder despite their resistance. Surprisingly, when he chose to impress, he could be engaging, charming, and good company.

William McMahon as Treasurer of Australia 1966 (photograph via National Archives of Australia/Wikimedia Commons)

William McMahon as Treasurer of Australia 1966 (photograph via National Archives of Australia/Wikimedia Commons)

Yet the singular focus and tenacity that served well in ministerial roles did not apply in the multitasking demanded of prime ministers. No longer was it feasible to push one line, backed by a strong department. Now there were multiple objectives to juggle, and a cabinet not to compete within but to manage. McMahon could not do it. Antipathy was by now so ingrained within his own ranks that his authority was undermined. And McMahon had none of the social intelligence needed to build a team. He came to think that he needed to do more and more himself, and, as that became increasingly untenable, would vacillate and succumb to panic. In consequence, he faltered on the public stage, ridiculed and diminished by Gough Whitlam, a far more polished performer.

Despite all, even in those final years, his government took initiatives – on childcare funding, urban and regional development, the environment, control of foreign investment, pensions, the independence of Papua New Guinea, and withdrawal from Vietnam – that facilitated what Whitlam and, later, Malcolm Fraser would achieve (and for which they would garner the credit). Arguably, in the light of Mullins’s comprehensive analysis, McMahon was not only a competent minister but – in policy terms – a more successful prime minister than Tony Abbott (whose only talent appeared to be for destruction) and possibly Malcolm Turnbull. I should add that Mullins – ever judicious – makes no such tendentious comparison.

One of the most fascinating features of this book is Mullins’s decision to interleave chapters of historical and political narrative with an insightful, astonishing, and often hilarious account of McMahon’s later attempt to have own story published. Winston Churchill, John Howard, and Keating (via intermediaries) have published more or less persuasive histories of their times, but McMahon’s sad and increasingly delusional enterprise should blow the whistle on all that. It is one of the most revealing instances you will find of the risks inherent in relying on a subject’s perspective in determining the historical chronicle.

All politicians want to control their legacy; to circulate the ‘truth’ as they see it. McMahon, even in this, was more driven than most. He interpreted and reinterpreted events obsessively, trying desperately to correct the distortions that enemies had put about. No amount of contrary evidence from others who were there could persuade him to alter his version – his memory was not to be questioned. All the same, just consider: who would have the temerity to tell Churchill, Howard, or Keating that they were wrong?

The crucial dynamic is this: McMahon had invested so much in the stories he generated to explain and justify himself to others that he came to believe in them absolutely. When his own voluminous notes proved to be incoherent and unpublishable, a succession of others were enlisted to edit and rewrite. Each of them came up against the gulf between what McMahon believed and virtually every other credible source. When each of them gave up the battle, McMahon would begin again to rewrite and adjust until, at last, he died. His story, at least as he wanted it, would never be told. But Patrick Mullins now has given us the real thing.

Comments powered by CComment