- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Trafficking in the Unsaid

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

W.H. Auden wrote, ‘Bless what there is for being’; and Beckett, of God: ‘The bastard, he doesn’t exist.’ Poetry swings between these poles, of celebration and deploration, lauds and plaints. At least, so it goes with poets who, otherwise disparate, have the trenchancy of Rodney Hall or Les Murray. Neither is a stranger to nuance, to evocation or implication, and any of these can be a tactical resource in mind or mouth for either of them; but the agenda is proclamation as often as not, and the sentiments are hued accordingly. At the end of most of their poems there is a pendant which says, in invisible writing, ‘dixit!’, and one usually sees why.

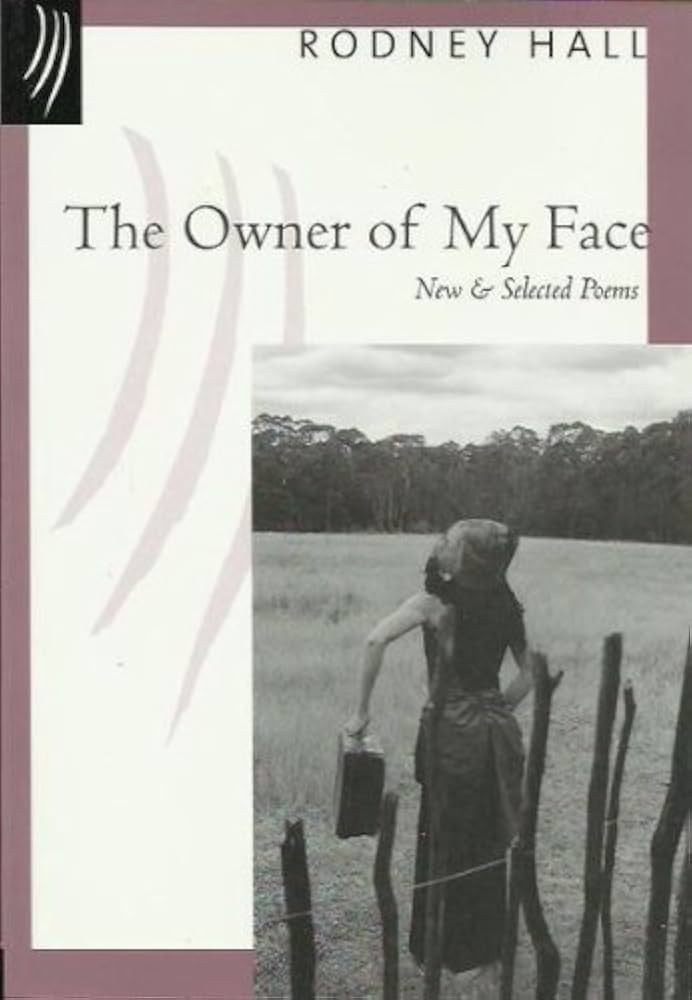

- Book 1 Title: The Owner of My Face

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Paper Bark Press, $39 pb, 216pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

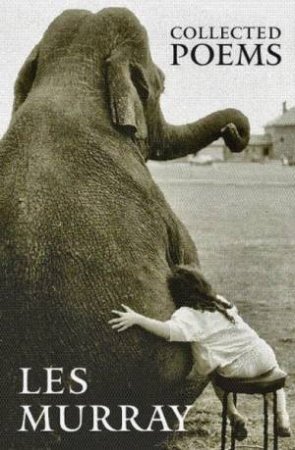

- Book 2 Title: Collected Poems

- Book 2 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $45 pb, 598pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Nobody nowadays needs telling that things do not have to turn out like this in poetry. A blind chameleon, I read, will still change colour to adapt itself to its milieu, and any amount of contemporary verse modulates incessantly and, it would seem, effortlessly, to look like nothing in particular as it inches across the contours of consciousness. By contrast, here are the endings of Hall’s ‘Gloria’ and Murray’s ‘The Gaelic Long Tunes’: ‘they raise the moon by force of song / her bright shell / bucking on reflections where the islands heave their bulk / into precious fleeting air / and vanish under trees of frosted spray // goodwill and peace to all mankind // our great ship nodding in the stately way of animals / the crew unburdens memories of harder times – meanwhile / among exotic growths cold death stands sentinel below’; ‘In disdain of all theatrics, they raised / straight ahead, from plank rows, their beatless God-paean, / their giving like enduring. And in rise / and undulation, in Earth-conquest mourned / as loss, all tragedy drowned, and that weird / music impelled them, singing, like solar wind.’

The settings of these passages are very different – a Pacific ocean cruising-space, and a Free Church Sabbath assembly – but the poems have in common an eagerness for transformation and a resoluteness in its effecting. Hall’s ‘trees of frosted spray’ and Murray’s ‘music … like solar wind’ are themselves impelled by a metamorphic zest. It is characteristic of both poets that the lifted voice should rise not only with a lyrical animation but in defiance of mortality’s subversions. Often, both Hall and Murray write as though conceding the reasons for a lowered voice but taking heart from the very precision of that saying, and thus winning through to a higher pitch.

Poetry is a likening, even when no metaphor is being deployed, no simile adduced. It knows that it is a miming, and, as often as not, is trying to find out what is being mimed. Murray and Hall are alike in their having copiously stocked memories and vaults of information, which they can be prodigal in displaying. But along with what might be called epic fervours there are lyric austerities – and a readiness to see what understatement can do, even in the midst of abundance. If Murray’s attention is solicited by that solar wind, he knows, too, what it is to be in disdain of all theatrics: if Hall notes the exotic growths, he is also himself a sentinel of cold death. Both of them know that, however precise and abundant the run of language may be, a poet is always trafficking besides in the unsaid, if not the unsayable.

Another way of putting this is to say that each courts surprise, a courting which can go like this: first, Hall’s ‘Youth, manhood, middle age’: ‘These aren’t the hands I had ten years ago / each cell has been replaced since then, / and yet they look the same though subtly worn / and maybe stiffer. Unsettling that I know / I’m not the man I’ve been, nor yet the youth. / This proves intrinsic (not to mere responses, / changing tastes or strength, or null defences) / that other flesh subserved another truth. // The symptoms passed me once – I made no study. / But now I analyse my yearly pattern / each loss declares itself in residue. / If only I’d unleashed one former body / in life too large and brave to fall forgotten! / Even my heart is old from growing new.’ Then, Murray’s ‘Succour’: ‘Refugees, derelicts – but why classify / people in the wreck of their terms? / These wear mixed and accidental clothing / and are seated at long tables in rows. // It’s like a school, and the lesson / has moved now from papers to round / volumes of steaming food / which they seem to treat like knowledge, // re-learning it slowly, copying it / into themselves, with hesitant spoons.’

Hall, for all his hospitality towards unbroached novelty, can also be fascinated by tradition’s potential yield. In the end, a sonnet is only as old as its maker needs, fears or hopes that it will be, and so it goes in this case. There is, in fact, a propriety in rehearsing a life’s half-span in one of the most durable modalities of European, as well as English, versification, but there is little point in doing so unless one has the confidence that the appraisal, this time, will help to revitalise the very instrument of gauging which undertakes it – the new wine itself renovating the old wineskin, as someone almost said. The essential novelty of this sonnet is the shift in voice from something analogous with a Shakespearean knottedness – ‘This proves intrinsic …that other flesh subserved another truth’ – to the Yeatsean, ‘Even my heart is old from growing new’, where the concluding acknowledgment is given its warrant in part by the imaginative distance gone to arrive at it. Poetry is all a coining of language, and the more convincing when it is clear that the coining has been at a cost.

A classic Murray gesture is the intervening question – that astonishing human invention without which extensive thinking is inconceivable, and which is, in principle, the venue or vector of surprise. Here, ‘but why classify / people in the wreck of their terms?’ both troubles and stimulates the attention it consults. Murray’s imagination can be at home in many regions, from jubilation to threnody, from charting to pleading; but the tilt of question is rarely far away. Asking – wondering, more properly – is the undeclared tide on which much of his most apparently firm claims are being carried: it is not that he often says that he does not know, it is more that one senses that he wants to know what the knowledge means. The ‘why classify / people’ here has a relevance not only when one thinks of social stereotyping, but also when it comes to the poem’s unfolding, and to the hesitant handling of nutritive knowledge. Understanding, for Murray, is typically carnal, progressive and transforming.

That fleshing of knowledge, along with a fleshing of ignorance, is something which has in fact exercised both poets from very early until their present passes. Hall, in ‘Intimations that Death is trying to make contact’, writes: ‘I take off my glasses and the world is fur / buildings turn to blocks of rain / the waterbeast we came from / imagines what a monster is // If I am magnified / I beg you not to put it down to / any trick of eye // People hurry off the ferry /sunlight in each foxy silhouette / star-bodies glow from the eclipse of flesh’; and Murray, in ‘The Meaning of Existence’, ‘Everything except language / knows the meaning of existence. / Trees, planets, rivers, time / know nothing else. They express it / moment by moment as the universe. // Even this fool of a body / lives it in part, and would / have full dignity within it / but for the ignorant freedom / of my talking mind.’

In both cases, what we are looking at is the elementary, and interminable, poetic taste for gawping at the obvious while declining to take it for the evident. There is a real sense in which the heart of a poet’s business – over and above the intellectual allegiances, the flood-tides of feeling, the vivacity of imagination, and all the craft of netting by night – is to know when and how to say yes, or no, or don’t know, in the face of the very experience which the poem is delivering. I think that this tactile delicacy, this sifting and assaying, is the essential gift of both of these poets. Neither’s work could easily be mistaken for the other’s – perhaps Hall is Ariel to Murray’s Antaeus – but they are comparably passionate when it comes to a quest for accuracy. The passages just quoted live in a different order of attentiveness, are keyed with a different precision, than is to be found in the talkative codes which dominate our customary prosings. Hall’s ‘If I am magnified’ is freighted with Yeats’s ‘to magnify and to bless’, Murray’s ‘ignorant freedom’ with the ironic plangencies of a world of baroque envisagings: but both proceed as if to be earthed is the only way to become exact – and exacting. The trick of the thing, which nobody I have come across can explain, is to root knowledge more and more deeply in the world’s brute realities while flourishing more and more defiantly the foliage of celebration. I doubt whether Hall or Murray can explain it either: but they both know how to do it.

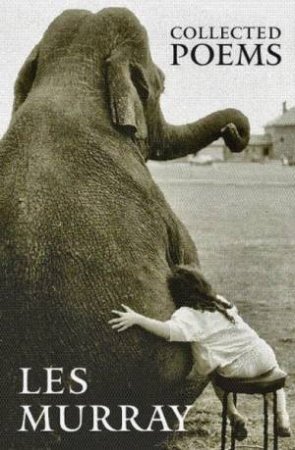

Rodney Hall’s title, on loan from Shakespeare, alludes to solitude: Les Murray’s jacket photograph of a small child hugging an elephant proclaims solidarity. But, in the end, any live poetry invests in both conditions, not so much in the interests of even-handedness as because it is, in Hall’s term, ‘foxy’, and is also, in Murray’s, of a piece with ‘trees, planets, rivers, time’. This is why we had one poem or another in the first place, and why, in time, they are collected or selected.

Comments powered by CComment