- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Resilient Laughter

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Books such as these build more bridges between Aboriginal and the wider society than any secondary source study or essay ever could. Black Chicks Talking and My Side of the Bridge tell the stories of a diverse group of Aboriginal women, most of whose lives would not meet the traditional requirements for published autobiography. On the whole, they are neither famous nor infamous. Most do not conduct their lives in public, nor try to. Perhaps they are swept up in a publishing trend that, at last, is acknowledging this country’s hidden voices, but their stories deserve to be told.

- Book 1 Title: My Side of the Bridge

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life Story of Veronica Brodie

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield, $24.95 pb, 199pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

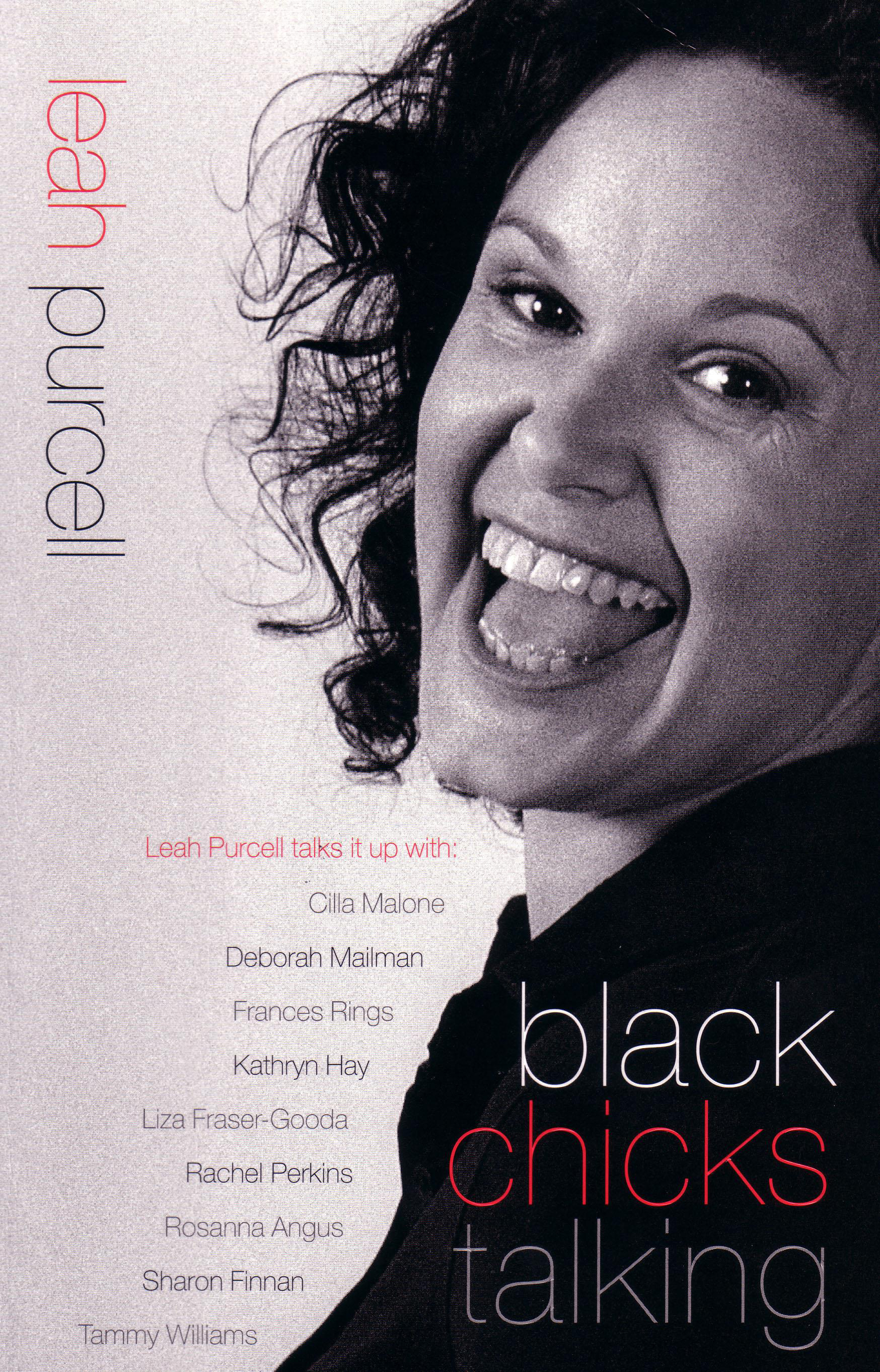

- Book 2 Title: Black Chicks Talking

- Book 2 Biblio: Hodder, $29.95 pb, 379pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Black Chicks Talking is essentially a compilation of interviews by Leah Purcell and nine Aboriginal women, but the book’s structure creates a much cosier experience than the straight question-and-answer format. Purcell interrupts the stories with her own anecdotes, comments or information. She asks the women to talk about which of the five senses they relate to most, and then asks them to recall their earliest memory of that sense. They sit for portraits and share a group dinner at the end of the book. The result is a fine collection of stories that will touch more than one nerve in most readers.

Purcell hoped her book would offer an insight into the lives of contemporary Aboriginal women and dispel some of the myths about Aboriginality. She points out repeatedly that the range of these women’s experiences does not preclude any of them from claiming their Aboriginal heritage.

The nine interviewees are from hugely varied backgrounds and include lawyer Tammy Williams, Labor MP Kathryn Hay, Mother Cilla Malone, Bangarra dancer Frances Rings, film-maker Rachel Perkins and community police warden Rosanna Angus. Some of the women were fully immersed in their culture from birth, some had to discover it for themselves, while others believe they are still to find it. They may be at different stages in their journeys, yet all share an instinctive sense of their Aboriginality – although that does not mean they are not confused about its meaning.

The complex identity crises that have developed from years of shaming could not be better demonstrated than in the stories of Deborah Mailman and Kathryn Hay. Both women have been labelled ‘first Aborigine’ achievers (Mailman with an AFI award, Hay in winning the Miss Australia crown), and both had indignant family members on the phone the next day, furious at their ‘claims’ of being Aboriginal.

While self-belief and a strong sense of identity are clearly prerequisites for all Aboriginal women today, we generally do not face daily confrontation to the same extent that Veronica Brodie did. Her strength is palpable from My Side of the Bridge. Sheer grit helped her to survive battles against the Aborigines Protection Board (surely the biggest misnomer ever given to a government body), alcoholism, white progress, and Royal Commissions. At a time when the day-to-day existence of most Aboriginal people entailed sufficient struggle, Auntie Veronica took on more battles than she needed to. This necessitated more than simply lowering her head and charging. The full weight of white authority bore down on many aspects of her life, and much of the time she had no choice but to accept it.

In the chapter entitled ‘How I Became a White Woman’, Auntie Veronica marries a ‘white’ man (although his mother was Aboriginal) and with ‘the stroke of a pen’ is exempted from the restrictions placed on Aborigines. She can drink, travel freely and work where she likes. She wears ‘dog tags’ around her neck to prove it. When the Aborigines Protection Board tells her that this marriage means she is exempted for life and will never be Aboriginal again, Auntie Veronica looks at her dark skin and thinks: ‘Who are these people?’ Contemporary consorting laws made it illegal for white people to mix with Aborigines. Legally, Auntie Veronica could not see or speak to her family, because they were Aboriginal and she was white.

The Hindmarsh Island bridge affair is probably the saddest lost battle of Auntie Veronica’s life. When a group of Ngarrindjeri women were pitted against the South Australian government and a million dollar development, the outcome was always inevitable. But it is still hard to comprehend the vigour with which sacred Aboriginal customs and beliefs, the equivalent of Western religion, were opposed.

The great charm of Auntie Veronica’s book is that it is written in her voice. For collaborator Mary-Anne Gale, it was important not to rewrite the story as a white editor. Auntie Veronica recounts her story as though telling yarns to her grandchildren. There is a sense of nostalgia for the good old days. The story skips years, moves back and forth, and sometimes repeats itself. There are truisms and gentle tickings-off.(She says that young people today couldn’t live through what her generation did.) Auntie Veronica wishes she could take her grandchildren to the mission where she was raised, ‘although it’s all spoilt now, Raukkan – they’ve got TV there and electricity!’

Publication of these personal stories suggests a growing acceptance of, for want of a better term, ‘Aboriginal’ English. This is, perhaps, an offshoot of a global trend that recognises the colonial dialects once called ‘pidgin English’ as languages in their own right. There are differences between the way Aboriginal Australians speak to each other and the way we speak to white people. Dialogue is usually informal, yet respectful; honest, but also ambiguous; and there’s always a great deal of humour. The emphasis on feeling rather than expression in our societies pervades these books.

As well as their passion and self-respect, these two generations of Aboriginal women share an unfailing sense of humour. Despite, or perhaps because of, the black history of race relations in this country, these women can still laugh. That is the greatest strength of all.

Comments powered by CComment