- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Beyond the Pale

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

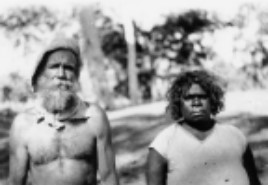

Roger Jose lived his adult life in Borroloola, married to an Aboriginal woman and beyond the pale of white civilisation, except in its most vestigial form. Nevertheless, he achieved a certain notoriety, through the writings of journalists such as Ernestine Hill and Douglas Lockwood. He also fascinated a young documentary film-maker named David Attenborough. Roger Jose claimed to be related to the respectable Jose family of Adelaide, which was not enthusiastic about acknowledging him. He lodged, an anarchic and glamorous figure, in the imagination of the young Nicholas Jose, and the tracking of his story provides the infrastructure that legitimises the writer’s journey into the north. Jose says: ‘I wanted the connection because I wanted to join myself to someone who had earned his belonging in this country.’ In the place to which he travels, this connection, real or not, is all-important, giving him an insider’s access to places and stories.

- Book 1 Title: Black Sheep

- Book 1 Subtitle: Journey to Borroloola

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $32.95 hb, 294pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Jose takes us, via circuitous and engaging routes, to Borroloola. He unearths histories and oral traditions that have accumulated around a community described in the Lonely Planet guide as ‘a dirty, unpleasant place – part town, part rubbish dump – with expensive accommodation and no redeeming features’. From this unpromising material, Jose excavates a fascinating account of the evolution of one of the crossroads of the remote north, and provides a glimpse into a dimension of Australian culture that is still poorly understood. He discovers, when he gets there, that it is impossible to separate the place from its mythology. ‘What is written about things here, where no-one could ever check, yields to the attraction of the tall story and, crossing the line into fiction, makes it taller.’ One such story, strange enough to be fiction, but true in all its essentials, is that of the Borroloola library. Established at the end of the nineteenth century, when aspirations for Borroloola were still high, it contained the classics and the literary canon of the time. Three thousand books, housed in a cell behind the court-house, provided a distraction and an education to the men who spent time in the cell for various misdemeanours. Bill Harney was one such character, Roger Jose another. After the library’s dispersal (part of it was eaten by white ants), it continued to fuel the weekly debates of the Borroloola hermits – my favourite being ‘Should Henry James be taken seriously?’

Ted Egan, a young patrol officer in the 1950s, describes the Borroloola hermits as ‘benign dead-beats and deros, who had read books’. Roger Jose, eccentric, bush philosopher, autodidact and combo (the pejorative term attached to a white man who cohabits with Aboriginal women), emerges as a man whose principles lie close to a genuine sense of equality and shared country. He crossed the boundaries of sex and race when to do so was not only socially unacceptable, but carried legal penalties. It raises the question whether only those who choose to live beyond the pale can manage the business of living in a genuinely compatible relationship with Aboriginal people.

Part of Nicholas Jose’s enterprise seems to be the search for an exemplary man. He might be drawing parallels with Roger Jose when he describes Matthew Flinders, the brilliant cartographer forced by an ageing and leaky ship to abandon the attempt to chart the Gulf of Carpentaria:

He was a masterless man in a gentlemanly sort of way, a man who was happiest making his own rules, a borderless man. He suffered from the existence of arbitrary borders imposed by class, gender and politics. He was drawn to natural boundaries, where land meets sea, believing he could breach them with understanding.

From Roger Jose’s country of Borroloola, Nicholas Jose travels eastward into the contested ground of corporate and Aboriginal aspirations, the fight between the Century zinc mine and the traditional people of the Gulf. In his account of Murandoo Yanner, the charismatic and controversial coordinator of the Carpentaria Land Council, there is a suggestion of the literary man’s admiration for the man of action. Intentional or not, the description of the Yanner clan’s influence on the politics of the Gulf makes it sound like a laid-back northern mafia. Aboriginal aspirations are neither clear-cut nor uniform, and Jose’s discursive voice unravels threads that tangle around an intractable core. He remarks, in one of the most important points made in the book: ‘The worst thing is that Aboriginal Australia is so often thought of as a problem to be solved. Hidden in this thinking is an unstated desire for a final solution, an aversion to the complicated, dynamic continuance of living peoples.’ Later, considering the ironies of white Australia’s desire for reconciliation, he quotes Alejo Carpentier’s Lost Steps: ‘they face the worst of all tyrannies, that exercised by those who love over the person who does not want to be loved.’

Black Sheep offers many felicities of language and of ideas, and deserves to be read slowly. Jose is an immaculate craftsman, and a pleasure to read. But it is in that urbane, discursive voice that the book’s central contradiction lurks. The writer moves through a difficult world in a privileged envelope, teasing out stories and histories, conjecturing about lives he will never have to experience. This is the writer’s paradox, the desire of a cosmopolitan traveller to expose himself to challenges that cannot really be felt when one has nothing at stake, no real way of choosing the hard ground. One is left with the sense of a sidetrack in the writer’s trajectory, a traveller’s tale, elaborated, erudite, beautifully told, but fundamentally disengaged.

Jose is clearly aware of this contradiction, remarking at one point: ‘the clue is to step back from abstraction, the frame of reference that an outsider seizes on, and move closer to the way people improvise actual lives.’ But how does one enter lives where eccentricity is often a cover for deeper flaws and griefs, and the choice to live on the outskirts of one’s own kind is driven by incompatibilities that can’t be glossed and idealised? The border that needs to be crossed is less one between black and white, which has always been permeable, but between comfort and discomfort, between the acceptable and the unacceptable.

At the book’s heart is the concern for connections, to country and to people, a concern that haunts many Australians, particularly those who have been insulated from the legacies of the frontier. As those legacies make themselves felt in the wider community, as the evidence is manifest that the border between black and white has been crossed since the beginning, and the descendants of those clandestine crossings articulate a louder and louder claim to be heard, books such as Black Sheep are an essential part of the conversation, the attempt to keep a dialogue going across the faultline.

Comments powered by CComment