- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: An Obsessional Storyteller

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An Obsessional Storyteller

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

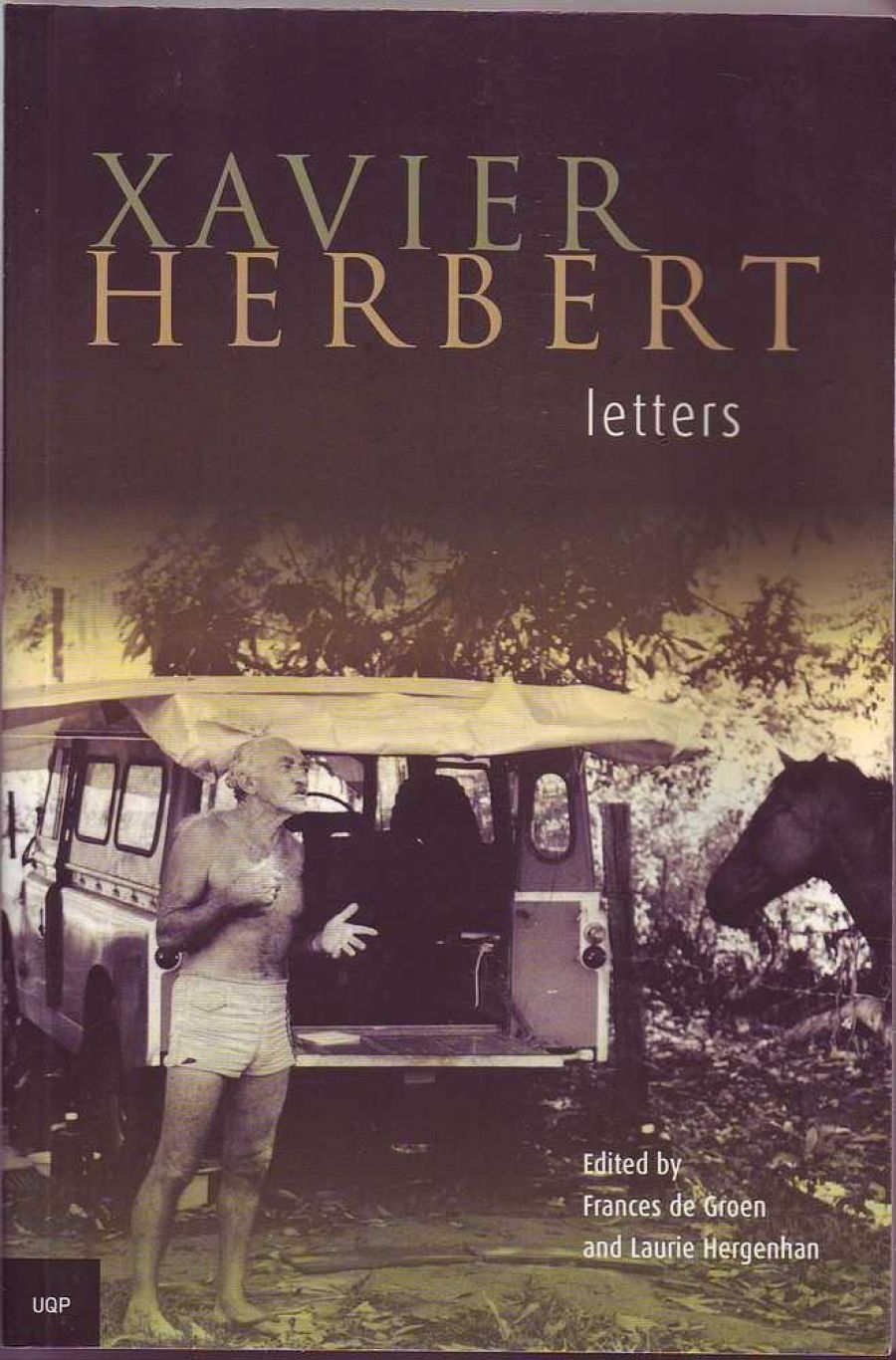

The cover of this substantial volume tells you what’s coming: it features a photograph of Xavier Herbert, sixtyish and fit-looking, standing behind the converted 4WD that constitutes his bush camp and dressed in nothing but a pair of stubbies. His eyes are blazing and a bit mad, his shoulders slightly hunched, and he looks as if he’s been holding forth for some time. To whom? For Herbert, it probably didn’t matter. You can see the man Vance Palmer described in 1941: ‘You feel he’s got a large chaotic world of jetting imagination inside him and it will always be desperately hard for him to write because he’s got a lot to say and he’s got this sort of garrulousness that keeps him talking about his matter instead of brooding on it and giving it form.’

- Book 1 Title: Xavier Herbert

- Book 1 Subtitle: Letters

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $45pb, 508pp, 0 7022 3309 9

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Living alone as much as he did – even at home he said he didn’t share the house with his wife Sadie, but lived in his backyard workshop – Herbert was free to shape his own image. His intense self-consciousness and conviction that he was a writer with a ‘great purpose’ are evident almost from the beginning of this selection. To almost all his correspondents, he presents himself as a roughhewn bush genius, too intent on his own writing to worry overmuch about other people’s feelings, let alone their work. It’s this facet of Herbert that can be hardest to take; sometimes his alpha male carryon about his work feels as if he

’s backing you into a corner, stabbing at you with his index finger while he harangues you. At the same time, there’s something disarming about anyone who could write, as he did to Laurie Hergenhan in 1970: ‘I don’t think I am an egotist at all.’ He certainly wasn’t an ironist.

Indeed, you can’t help liking him (though being thankful, perhaps, that you never had to meet him). Behind his bombast is passionate sincerity and total belief in what he was trying to do. Herbert was the kind of writer who transmitted his own experience and observation into his work, which was also driven by a powerfully polemical turn of mind; one of the pleasures of this selection is tracing his progress in developing his ideas and convictions into the shapes of fiction.

‘I have a black man’s mind, I can see things in blackfella fashion,’ he boasted in 1936. Self-delusion, almost certainly, but his practical knowledge of the Aboriginal people, as well as his furious disgust about the way they were treated, are obvious from very early in his career. As de Groen and Hergenhan point out, his vision for Australia, articulated in various ways from Capricornia (1938) to Poor Fellow My Country, was an independent republic recognising prior Aboriginal possession of the land and based on egalitarianism and social justice, including a decent wage for Aboriginal workers. He wasn’t always consistent - at one point, like many of his generation, he supported assimilation -but, basically, he felt that in most ways Aboriginal culture was far superior to white. His attempts to articulate all these convictions made him, as Hergenhan said, ‘An Obsessional Story-Teller on a Grand Scale’.

Herbert used some of his correspondents as sounding boards, even accomplices: first P.R. Stephenson, who guided the publication of Capricornia, then Beatrice Davis, general editor at Angus and Robertson, who published Soldiers’ Women (1961). His conviction and enthusiasm seduced even the cool and professional Davis, who wanted him to fulfil his ‘purpose’ while trying to make him conscious of such details as excessive length, wooden characterisation and possible libel problems. In the end, she was deemed unworthy, and Herbert never forgave her for doubting him. His last colleague, who showed signs of wilting under the barrage, was Laurie Hergenhan, who became his chief confidant in the writing of Poor Fellow My Country.

Nearly half of this text is taken up, in one way or another, with this novel: Herbert conceived the original idea as early as 1937. It’s one of the most rewarding parts of the book; when he’s really working, Herbert drops the inflated language and windy rhetoric and writes simply and strongly. His letters to Sadie in 1964 are like overhearing him talking to himself as he struggles with the huge mass of material. Here, de Groen and Hergenhan are particularly good, their footnotes attentively guiding the reader through the maze.

Indeed, this collection of letters depends on its footnotes; there are very few pages without them. Mostly, they explain where Herbert was at various times, point out inconsistencies and contradictions in what he has written, and – most usefully for students of Herbert’s work – indicate places where his life and writings intersect. They can also be fun. When Herbert is more than usually grandiose, the editors are there to dig him in the ribs. ‘I think I may safely say that I am known, and respected and trusted and in many cases even loved in every Aboriginal horde in the Territory north of Newcastle Waters’ brings forth an abrupt ‘Inflated self-recommendation’. Other comments include ‘He could also be a great bore’ and ‘Wishful thinking’.

There were times when I wished the editors had filled in more of the emotional gaps. Herbert’s affair with Dymphna Cusack, and its effect on Sadie, are surely worth more than one terse note. The relationship with Sadie, too, could have been more fully discussed, a brief reference to Herbert’s ‘callous behaviour’ during his wife’s final illness explained. The book ends suddenly, in 1979, though Herbert lived until 1984: surely he wasn’t silent for five years? For these reasons, I think, the editors’ claim that this is a ‘warts and all’ portrait is not completely accurate.

Generally, though, this is an admirably well-organised selection of letters, which will be appreciated by students of Herbert’s work. For those of us who cherish an appreciation of eccentric behaviour – as long as we don’t have to deal with it too often – it’s also a highly entertaining read.

Comments powered by CComment