- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

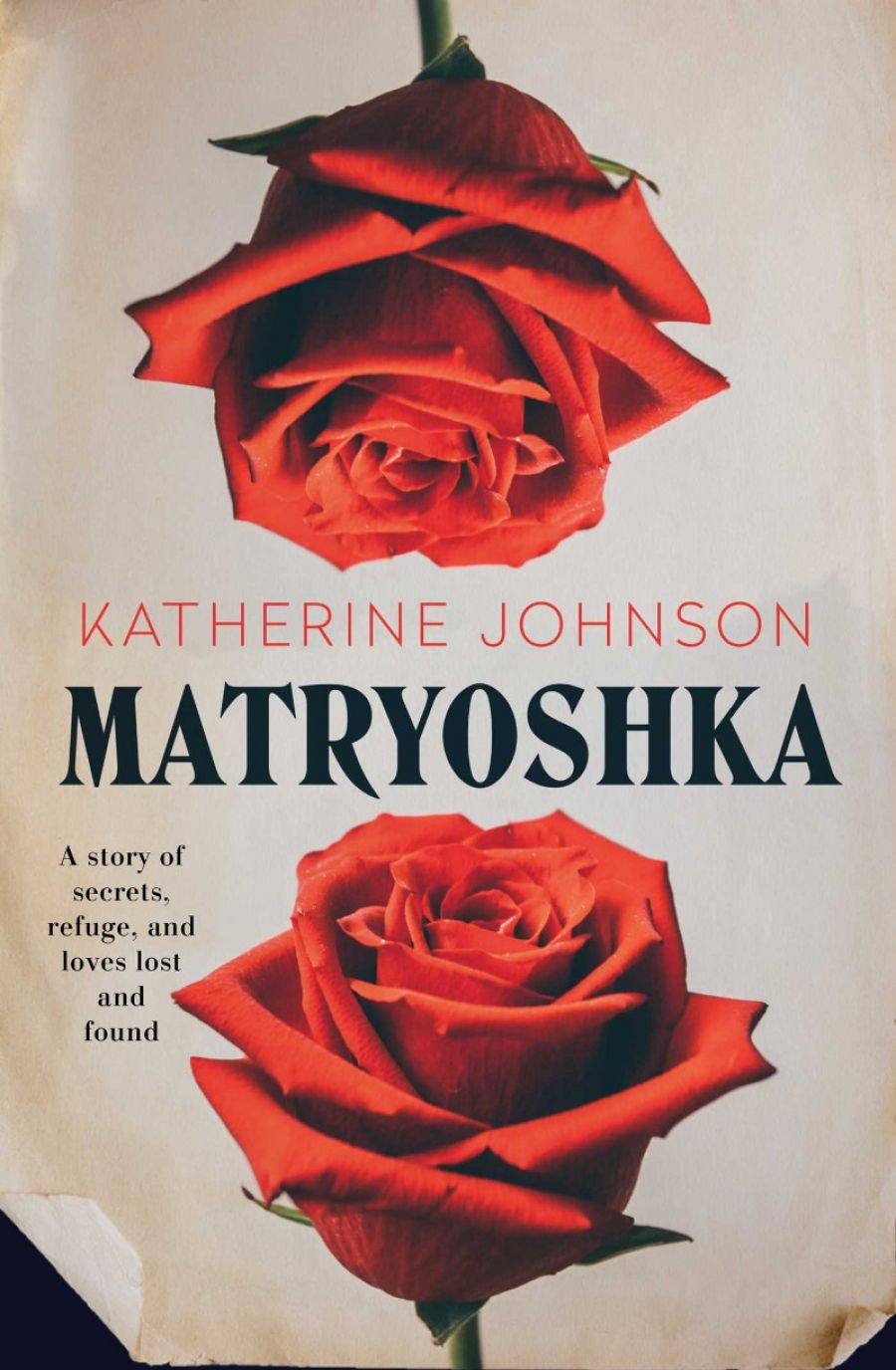

- Custom Article Title: Alice Nelson reviews 'Matryoshka' by Katherine Johnson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Half a century ago, the Palestinian writer Edward Said described the state of exile as ‘the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home’. Its essential sadness, he believed, was not surmountable. The crippling sorrows of exile and estrangement ...

- Book 1 Title: Matryoshka

- Book 1 Biblio: Ventura Press, $29.99 pb, 400 pp, 9781925384635

The matryoshka of the novel’s title refers to a set of wooden Russian nesting dolls, each one containing a smaller version of itself; a continuous chain of women inextricably linked to each other by destiny and – in the world of the novel – by a complicated love that is often as painful as it is consoling. At the centre of Matryoshka is a compelling familial quartet: the formidable Russian exile Nina, her mysterious daughter Helena, wounded granddaughter Sara, and Sara’s own small daughter, Ellie. Husbands and lovers circle these women, but they remain in the background; the story here belongs mostly to Sara, and it is her unspooling of familial mysteries that drives the narrative. Each character has been menaced by history in a different way, but each is irrevocably bound to the other, and their personal stories refract each other in fascinating and often unexpected forms.

When the novel opens, Nina has just died and Sara has retreated from her disintegrating marriage to live in her grandmother’s home in Tasmania – the place where she was raised. Sara’s mother, Helena, who abandoned her as a baby and is now a successful paediatric heart surgeon, hovers on the fringes of the story for much of the novel, busy saving other lives. Helena’s desertion of her family and her stubborn refusal to reveal the identity of Sara’s father casts her as a cruel villain until long-withheld truths about her past begin to emerge.

The Russian émigré Nina, such a powerful force in Sara’s life, is never quite rescued from the aspic of memory, but this may be appropriate for a novel preoccupied with lacunae and omissions. Matryoshka’s deep obsessions are dislocation and loss, and there is an unnerving sense of attenuation that shadows the story despite careful craftsmanship and expertly balanced plotting.

Amid this swirl of familial fractures and re-engagements emerges another narrative strand that works in a kind of skilful, contrapuntal motion. Sara befriends an Afghan asylum seeker named Abdhul and soon becomes deeply involved in his life. Johnson renders convincingly and poignantly Abdhul and his compatriots’ attempts to make meaningful contact with their new surroundings, only to find themselves in a place where they are feared, misunderstood, and subjected to all the cruel exclusions of prejudice. In the schoolyard, mothers fret about a new Hazara student, wondering if he poses a danger to their children. There are whispers about polio and tuberculosis, and more amorphous fears about the disturbing history the small boy might contain. Intolerance and ignorance abound, eventually shading into an act of horrifying brutality.

The miseries of Abdhul and his friends are compounded by an official heartlessness that borders on a variety of bureaucratic sadism. The asylum seekers are sentenced to a cruel limbo that seems devised to deny them dignity; one of them, ‘sick with waiting’, takes his own life.

Writing about the encounter between privileged Westerners and powerless non-white refugees is fraught ethical and representational territory. Matryoshka could so easily have slipped into well-intentioned polemic or mawkish didacticism, or the more insidious trope of objectifying incomprehensible anguish as titillating, literary fodder, but Johnson handles this material deftly and sensitively. Her protagonist is painfully alive to the limits of her own understanding, the complex antinomies of exile, and the odd slippages in the soul it can create are painstakingly limned.

Katherine Johnson (photo via Ventura Press)The world of Matryoshka is haunted by fractures and loss. Marriages fail, friendships fragment, new love falters. The past is ever there, slipping stealthily through the membrane of the present and tarnishing the lives of Johnson’s characters. The novel is rife with solitary wanderers and disinherited souls: people staggering from aching and often irremediable losses. And yet, despite all of this, normal life beckons. There are classroom politics, workplace dramas, wildflowers to pick, holidays to the seaside. The Tasmanian landscape is rendered in exquisitely lyrical prose, and the joys and exigencies of everyday existence provide a quickening of life to a novel that may otherwise have submerged itself beneath the heavy freight of all this sorrow.

Katherine Johnson (photo via Ventura Press)The world of Matryoshka is haunted by fractures and loss. Marriages fail, friendships fragment, new love falters. The past is ever there, slipping stealthily through the membrane of the present and tarnishing the lives of Johnson’s characters. The novel is rife with solitary wanderers and disinherited souls: people staggering from aching and often irremediable losses. And yet, despite all of this, normal life beckons. There are classroom politics, workplace dramas, wildflowers to pick, holidays to the seaside. The Tasmanian landscape is rendered in exquisitely lyrical prose, and the joys and exigencies of everyday existence provide a quickening of life to a novel that may otherwise have submerged itself beneath the heavy freight of all this sorrow.

Sometimes the novel strains faintly under the intensity of such disparate universes of experience and varieties of traumatic inheritance, but this is overcome by Johnson’s restrained and authoritative writing and by her refusal to bestow a facile redemption upon her characters. Matryoshka is essentially about the quest to reassemble a sense of self from the discontinuities of exile and estrangement. Some of the novel’s wanderers find a way home and some rifts are mended, but Johnson is aware that some wounds are too deep to heal fully and that some sorrows are insurmountable. It is this painfully held truth that makes Matryoshka such a fascinating and authentic meditation on the long shadows cast by loss.

Comments powered by CComment