- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Anthony Lynch reviews 'When I Saw the Animal' by Bernard Cohen

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As a boy, I watched with fascination an early sci-fi horror film, The Blob. After a meteorite lands in Pennsylvania, a small, gelatinous blob emerges from the crater. Starting with an inquisitive old man who probes this runaway black pudding with his walking stick, the blob proceeds to consume, literally, everything ...

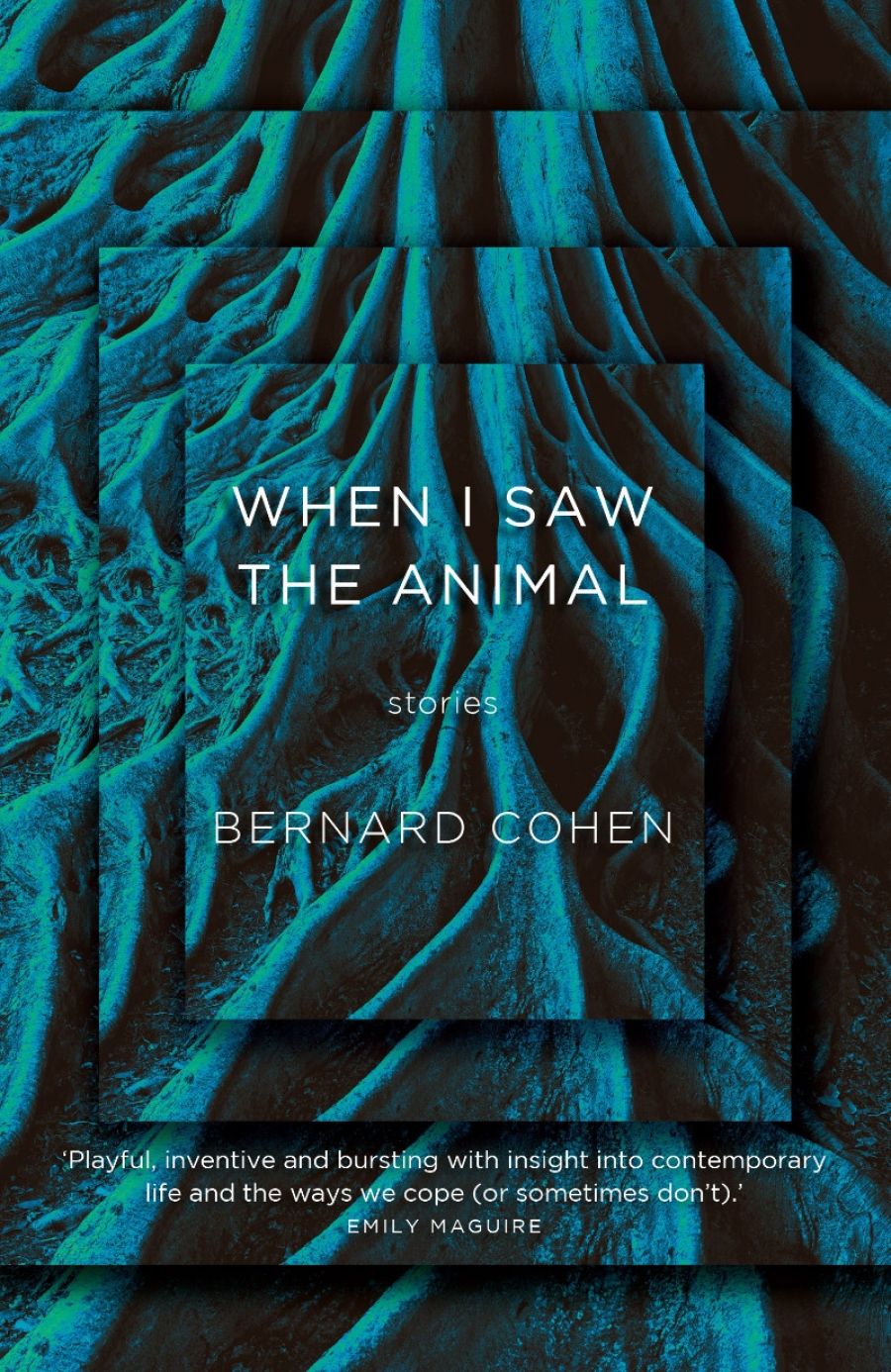

- Book 1 Title: When I Saw the Animal

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $22.95 pb, 237 pp, 9780702260216

While the title story of Bernard Cohen’s short story collection is a very different beast from the schlock 1958 film (I have avoided the 1988 remake), which may have inadvertently provided a metaphor for twentieth-century Western consumerism, it offers a similar portrait of an uninvited animal, or thing, disrupting normalcy. One night, sitting at home after a number of drinks, the narrator of Cohen’s story sees, or thinks he sees, an animal dart across the room. Was it a rat? Did he imagine it? He can’t be sure. Days pass, and he glimpses the animal again. Thereafter, sightings, or half-sightings, become more frequent, and the animal – or is it now animals? – grows in size. The narrator, metaphorically, consumes himself in his attempts to fathom this takeover of his home and his consciousness.

When I Saw the Animal is Cohen’s first collection of short stories, but he is the author of five novels, the second of which, The Blindman’s Hat, won the 1996 Australian/Vogel Award. The title story is an exemplar of a number of stories in which animals, domestic pets included, are not so much a comfort as disruptors moving in mysterious ways. Who can know what they are thinking? Why are they even present? They appear from nowhere, to stay or depart according to unreadable patterns; emblems of the lack of clarity, of perspective, with which Cohen’s characters must deal – characters, in the way of Kafka, absorbed in detail yet unable to penetrate a world with structures blurrily apprehended.

While this blob-meets-Gregor Samsa introduction may suggest a trite and even nostalgic take on modernist angst, Cohen has a marvellous command of the nuances and intricacies of language, its connotations, gaps, and slippery hold on what we might conceive of as reality. His dialogue is packed with sardonic wit and the nonchalant sword-crossings of domestic life. Often impulsive, a typical Cohen protagonist is a male who fixates on an animal, object, or a course of action that brings household disturbance and comic grief. The opening story, ‘Gilberto’, is a prime example. Opposed by family members, usually female, with sharp tongues and acid observations, he blithely pushes on.

Cohen himself is not afraid to push stories to the absurd – a dog moves in, family members move out; a man lets himself into the wrong house to find a large and wild member of the feline family behind the bathroom door. Not all end disastrously. Often a kind of new normal asserts itself by the story’s end; other times Cohen is happy to embrace ambiguity, abandoning resolution. Occasionally, stories forgo conventional narrative structure, being playful explorations of language, hermeneutics, and identity. In ‘Fifty Responses to the Ravens Paradox’, figures that include a white shoe, a blind woman, a tree, and a crow make propositions variously supported or contradicted by other voices. Interspersed with longer stories, yet other stories are microfictions or have the force and brevity of prose poems.

These stories were written over approximately two decades. Some very short contributions seem more like occasional experiments than considered contributions to a coherent whole. Arguably all, however, explore how meaning is constituted. ‘Conversations with Robots’, in which a scripted ‘You’ responds as robotically as the robot programmed for empathy, is a hysterical call-and-response going nowhere.

Bernard CohenCohen’s protagonists can lean towards the solipsistic, yet the author has a clear-eyed, unsentimental view of human frailty. Characters need not, of course, be likeable, but the self-absorption of many, combined with scenarios that, however deliberately, push the limits of credibility, can make emotional investment difficult to muster. The best stories, however, are sardonic portraits of flawed individuals whose self-serving doggedness is coupled with flashes of insight and brilliant wit. In ‘A Chinese Meal, Uneaten’, the self-aware narrator recalls eating bad Australian Chinese food with his then wife in an episode that captures the ruin of their marriage. Its gems include a description of the oily fried rice – ‘one might be confused as to whether the frying process had already taken place or whether the table was a stop-off point on the way to the pan’ – while this same narrator recalls histories of casual racism when he observes: ‘Whenever in an ethnic restaurant, it was our practice to doubt the provenance and more particularly the species of the meat.’ Later in the collection, ‘Orangeade’ is a wry, sympathetic portrait of everyday opportunism.

Bernard CohenCohen’s protagonists can lean towards the solipsistic, yet the author has a clear-eyed, unsentimental view of human frailty. Characters need not, of course, be likeable, but the self-absorption of many, combined with scenarios that, however deliberately, push the limits of credibility, can make emotional investment difficult to muster. The best stories, however, are sardonic portraits of flawed individuals whose self-serving doggedness is coupled with flashes of insight and brilliant wit. In ‘A Chinese Meal, Uneaten’, the self-aware narrator recalls eating bad Australian Chinese food with his then wife in an episode that captures the ruin of their marriage. Its gems include a description of the oily fried rice – ‘one might be confused as to whether the frying process had already taken place or whether the table was a stop-off point on the way to the pan’ – while this same narrator recalls histories of casual racism when he observes: ‘Whenever in an ethnic restaurant, it was our practice to doubt the provenance and more particularly the species of the meat.’ Later in the collection, ‘Orangeade’ is a wry, sympathetic portrait of everyday opportunism.

A number of stories have narrators believing they are subject to, or part of, a test or social experiment the nature of which escapes them. The final story, ‘Attributed to Jeremiah’, evokes a post-apocalyptic suburbia hinting at the aftermath of failed experimentation. It’s a powerful piece with lines many poets would be proud of. ‘English is a dismemberingly cruel idiom,’ the narrator tells us, ‘and it fits this world too well.'

Comments powered by CComment