- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Brian Matthews reviews 'Half the Perfect World' by Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In August 1964, Charmian Clift returned to Australia from the Greek island of Hydra after nearly fourteen years abroad. As Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell portray her return – a description based, as always in this book, on solid or at least reasonably persuasive evidence – she ‘was leaving her beloved Hydra ...

- Book 1 Title: Half the Perfect World

- Book 1 Subtitle: Writers, dreamers and drifters on Hydra, 1955–1964

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 438 pp, 9781925523096

Meanwhile, in 1965, I saw an advertisement in the TLS for a teaching job on the island of Spetsai at the school John Fowles taught at and a version of which appears in his 1965 novel, The Magus. Famous mostly for its flaws (Woody Allen said if he had his life over again he’d do everything the same except read The Magus), this strange novel nevertheless appealed to me irresistibly. Footloose, bulletproof, powerfully bitten by the lure of audacious decision – I applied for the job and wrote to Charmian Clift – quite possibly the last thing she needed. Her reply, on December 9 from her Cremorne flat, was prompt and generous: ‘I will tell you what I can, although heaven knows how much things have altered in even a year.’ She detailed with great verve what life might be like:

… just wait and see how you fall into Mediterranean habits, and how pleasant it is to be a little bit free to go and look and enjoy and sit around tavernas. [Spetsai] is a lovely island … all the yachts come in in summer and there are thousands of people to meet and be sociable with … the college might drive [you] mad, overrun as it is by spoilt middle-class Athenian youth, who can be odious. But then you have Hydra just next door … and you can escape. I don’t know what else to tell you. Except don’t miss this experience if it is offering … If you have any specific questions please don’t hesitate to ask me. And good luck – as if you need it – you are so lucky to have this chance. Sincerely, Charmian Clift.

This admittedly somewhat self-indulgent anecdote is interesting because Clift’s ebullience and wholehearted engagement are at odds with Genoni and Dalziell’s undoubtedly accurate evocation of her post-Hydra decline. It was as if an eccentric letter from someone apparently as impetuous as she had been when she and George Johnston resolved to ‘go and live in the sun’ briefly rekindled Clift’s remembered joy in being among Greek people who, as she notes in the letter, ‘are so heart-warmingly friendly on islands’. But this must have been only a brief moment of light in the gloom, as Genoni and Dalziell make clear:

Despite Clift’s success on returning to Sydney, the effect on her was devastating …. she [missed] her island life … struggled constantly with the pressure of newspaper deadlines … suffered protracted depression and eventually took her own life in July 1969, at the age of forty-five.

Half the Perfect World is dominated by Clift as either a volatile presence or an offstage figure of whose brio, élan, and mercurial temperament one is always conscious. Not even Johnston himself – somehow sepulchral, at times self-absorbed – has comparable mettle. But for all their centrality, Clift and Johnston are part of a large and evolving cast of characters. The authors range through their ranks with assurance, wit, and poise. Leonard Cohen, Rodney Hall, Sidney and Cynthia Nolan, Nancy Mitford, Sue and Mungo MacCallum, Anthony Perkins, and Melina Mercouri are only a few of the immediately recognisable visitors.

You need a bit of luck as a researcher, and Genoni and Dalziell record their debt to Life photographer James Burke, whose fifteen hundred photos of Hydra and the expatriate community were commissioned but never published, and to the rather hapless New Zealander Redmond Wallis – ‘a key participant in the [Hydra] action’. His manuscript The Unyielding Memory is an ‘unvarnished account of numerous significant incidents and individuals who are only ever thinly disguised’, but whose real identities Wallis makes clear in an accompanying list. The authors didn’t personally discover these hitherto-neglected sources, but they recognised their value, and they use them with tact and imagination to run a binding thread through a narrative otherwise threatened by the implosive force of innumerable names, faces, episodes, movements, liaisons, and enmities.

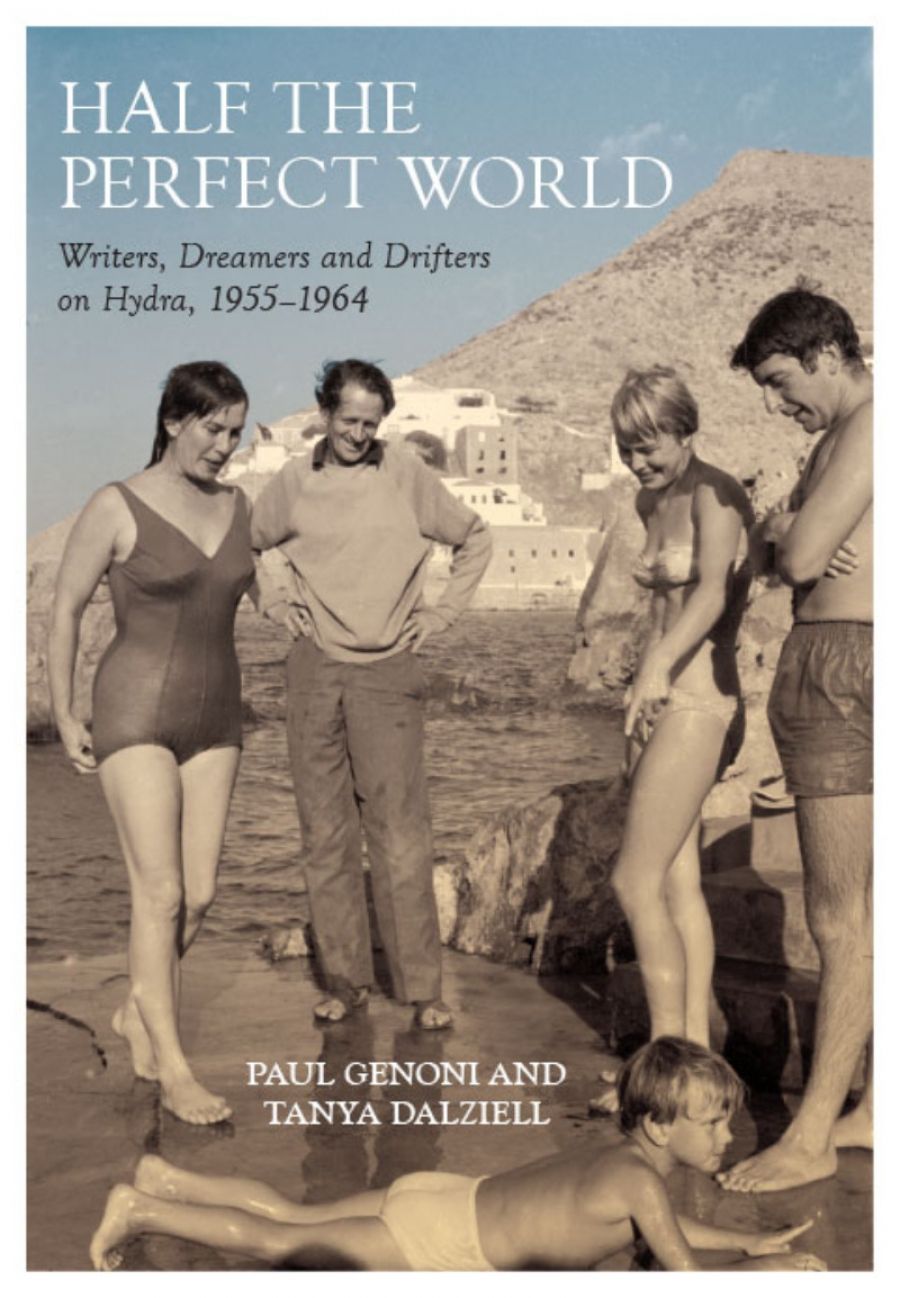

Charmian Clift (second from left), Leonard Cohen (second from right), members of the Katsikas family, and others, c. 1960 (Johnston and Clift Collection)

Charmian Clift (second from left), Leonard Cohen (second from right), members of the Katsikas family, and others, c. 1960 (Johnston and Clift Collection)

The book is studded with Burke’s photos, but they are never mere decoration; they are liberally captioned, and the authors refer to them in detail, interpreting them where necessary and placing them in the context of their Hydra story at appropriate points, a manoeuvre which Burke facilitated by taking photos in series, as if they were ‘stills’ in a movie. Wallis’s papers are similarly ubiquitous and are, like the photos, held to important narrative account. Moreover, each chapter ends with a quoted piece from Wallis, a nice touch that sometimes acts as a ‘dying fall’, sometimes as commentary, sometimes as an elegiac summary or astringent afterword.

Half the Perfect World benefits immeasurably from the authors’ skilled and indefatigable research. As with any broadly biographical/critical enterprise, they have to chance their arm now and then. The word ‘likely’ precedes a number of their suggestions, and sometimes, when the strain tells, the prose falls clunkily back on contemporary conversational cliché: the usually redundant and meaningless ‘in terms of’, for example, gets far too liberal a run. Nevertheless, one quickly feels confidence in the integrity of the narrative and its narrators.

George Johnston and Charmian Clift shopping dockside, 1962 (photo by Colin Simpson)

George Johnston and Charmian Clift shopping dockside, 1962 (photo by Colin Simpson)

There are some longueurs, but these are in a sense intrinsic and unavoidable. The protagonists themselves recognised the threat of tedium and the dictates of unwanted but unavoidable, confined routine. The authors quote Clift’s description of the ‘hours lingering on the agora’: ‘mostly we talk, individually, severally, and at last all together, hurling and snatching at creeds, doctrines, ideas, theories, raging through space and time like erratic meteorites’. The meteorite image is apposite. Burnout seemed always a distinct possibility, made the more likely by the pressure of modern tourism (a topic on which Genoni and Dalziell are interesting and well informed), but especially by the ever more fraught social dynamics as the expatriate core grew, fractured, aged, and was challenged by new blood.

Hydra’s place in the history of Australian literary bohemianism remains tendentious despite Clift and Johnson’s individual contributions, especially Peel Me a Lotus (1959) and My Brother Jack (1964). Genoni and Dalziell may sense this in their conclusion, which, imagining ‘a future free from the strait-jacket of a stale inheritance and … landscapes fit for bold new dreams’, seems to gesture uncertainly back to, rather than beyond, a long-lost bohemian Hydra. But that’s a quibble: Half the Perfect World is a fascinating, impressively researched, well-told story about a place and its moment that time and tourism have since overrun.

Comments powered by CComment