- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Review Article: Yes

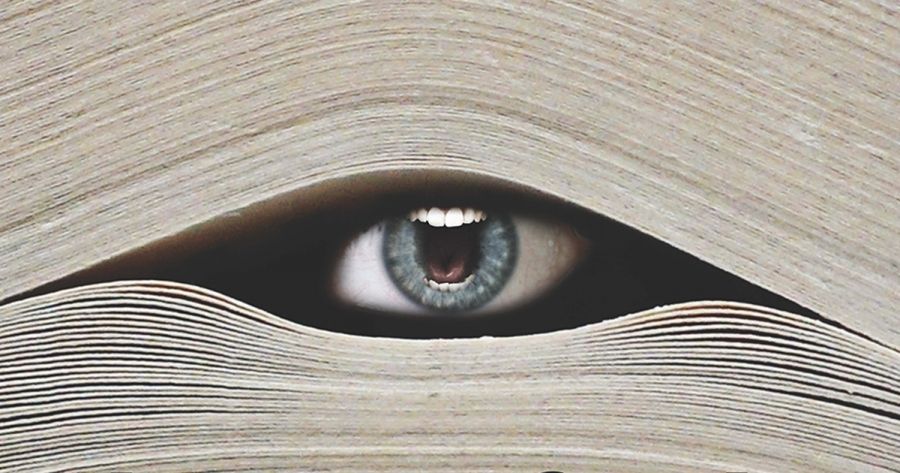

- Article Title: The art of pain

- Article Subtitle: Writing in the age of trauma

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Inspirational Memoirs, Painful Lives, Real Lives – these were the polite terms, the labels you might find on bookshop shelves, but the term that stuck was Misery Literature. The books had plaintive titles like Tell Me Why, Mummy, and Please, Daddy, No, or single-word gut-punches like Wasted, Fractured, and Damaged ...

Misery Literature quickly became ‘the book world’s biggest boom sector’, but there was always a whiff of ambulance-chasing about it, the stink of lucrative embarrassment, of voyeurism. It was an embarrassment compounded by the fact that mis-lit sold far more copies in supermarkets than bookshops, shelved next to the gossip magazines and chocolate – dismissed as traumatised chick lit (approximately eighty-five per cent of buyers were women). Publishers spoke of their mis-lit catalogues with thinly veiled disgust; they described entering the market as ‘getting our hands dirty’. Critics wrote, ‘These are things you should tell your therapist, not the whole world.’

When a slew of mis-lit memoirs were exposed as hoaxes and frauds in the mid-noughties, there was a hearty dose of critical Schadenfreude and a tentative sigh of relief – surely this grotty little phase of laundry-airing must be nearing its end.

A decade later, Hanya Yanagihara’s second novel, A Little Life (2015), was nominated for a US National Book Award, shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and awarded the Kirkus Prize. Extensively and exultantly praised for its transgressive audacity, its ‘subversive brilliance’, A Little Life is an 800-page immersion into a mind bound – a life irredeemably altered – by extraordinary childhood trauma. ‘You will find it hard to find another mainstream literary fiction that equals the most egregious misery memoir for its plotline,’ wrote one columnist, on her way to praising it as ‘must-read’. ‘In an age in which, we are told, a few clicks of the mouse can bring us face on with visual evidence of this kind of abuse, to be able to evoke nausea and disgust through the written word is remarkable,’ wrote another. It was a best-seller, too; the bookshop kind.

Hanya Yanagihara (photo by Jenny Westerhoff/Penguin)

Hanya Yanagihara (photo by Jenny Westerhoff/Penguin)

Yanagihara’s novel was released in March 2015; by July it felt as if every reader I knew – at home in Australia and then at my university in the United States – was pressing their copy of it into my hands with the same exigent spiel: the abuse was beyond horrific, they warned, but there was something about the book that was utterly – bodily – compelling. That was the word I heard again and again: compelling. It’s rare to encounter literary discussion of such dissonant zeal, such enthralled distress. When I finally read the novel, I did feel compelled, but not captivated as much as captive.

Yanagihara’s orphan protagonist, Jude, is abandoned in a skip, raped by monks, pimped out to truck drivers by a rogue priest, bullied and beaten in state care, and eventually imprisoned by a diabolical psychiatrist who runs him over with a car. This catalogue of horrors is psychological prologue to an adulthood in which Jude is mired in cycles of vividly – viscerally – rendered abuse and trauma: a Jekyll-and-Hyde-like lover who pushes a wheelchair-bound Jude down the stairs, elaborate self-harm, a panoply of debilitatingly painful medical complications, profound personal loss, and the omnipresent spectre of suicide.

The suffering of A Little Life is ornate and unremitting. Baroque. I finished the novel on the morning of Halloween. That night I dressed as a skeleton and tried to shake my raw discomfort – an inchoate mix of cultural isolation, ethical queasiness, and vicarious pain – in a suit of glow-in-the-dark bones. That was three years ago, and I’m yet to shake it. Now, I’m trying to give it intellectual shape – to understand how, in the space of a decade, the narrative qualities for which misery literature was widely dismissed and ethically condemned have become the qualities critically lauded at the dark edge of mainstream literary fiction. To try and understand why (or if) it matters.

This summer in London, the window of every Waterstones bookshop – at the airport, on the high street, in the suburban shopping centre next to my Airbnb – seemed to showcase Gabriel Tallent’s début novel, My Absolute Darling, new to paperback and coloured like some kind of stinging insect: an incendiary wasp yellow. There was a hive-like quality to the buzz, too. ‘One of the most important books you’ll pick up this decade,’ exclaimed Harper’s Bazaar. ‘The word “masterpiece” has been cheapened by too many blurbs,’ blurbed Stephen King, ‘but My Absolute Darling absolutely is one.’ Online journal, Electric Literature, asked ‘Does “My Absolute Darling” Deserve the Hype?’ and concluded, ‘this is the kind of book that can change the world, and I sincerely hope it does’.

Gabrielle Tallent (photo via Penguin Random House)Tallent’s novel is the story of Turtle, a fourteen-year-old girl who lives with her survivalist father and war-veteran grandfather in the relative isolation of Mendocino, on the Californian coast. By day she obsessively cleans a small arsenal of big guns, sharpens her knives, and wanders the headland wilderness – intimate with its secrets and rhythms, ever-wary of its dangers. At night, her father drags her from her bedroom into his. She also understands his secrets, rhythms, and dangers, and she adores and loathes him for them.

Gabrielle Tallent (photo via Penguin Random House)Tallent’s novel is the story of Turtle, a fourteen-year-old girl who lives with her survivalist father and war-veteran grandfather in the relative isolation of Mendocino, on the Californian coast. By day she obsessively cleans a small arsenal of big guns, sharpens her knives, and wanders the headland wilderness – intimate with its secrets and rhythms, ever-wary of its dangers. At night, her father drags her from her bedroom into his. She also understands his secrets, rhythms, and dangers, and she adores and loathes him for them.

‘I wanted to write her so that the damage we do to women would appear to you, as it appears to me, real and urgent and intolerable,’ Tallent explained in a 2017 interview with the Guardian. As in Yanagihara’s book, Tallent’s approach is one of unflinching excess. A breathlessly rococo suffering; Nabokov by way of Bret Easton Ellis. Turtle’s father holds a Bowie knife to her crotch as she does pull-ups from a ceiling beam; he forces her to shoot a coin from the hand of another child, and then to amputate part of the finger she damages when the stunt goes wrong; things do not end well for the family dog. And every detail of every rape is felt, an uneasy, incestuous braid of terror and yearning.

I read every word of Tallent’s novel. I kept reading even after I knew I did not need or want to read any more. I stayed because I felt as if I were being dared to stay, that I was in a game of chicken with the narrative, and that to leave would be to admit some sort of emotional or empathetic weakness. I left the novel furious, not at it but at myself. This time I didn’t feel captive; I felt complicit. I was reminded of those rogue psychology experiments from the 1970s – Stanley Milgram’s obedience trials – where participants were convinced to administer ‘fatal’ electric shocks to strangers.

I am far from the first reader or critic to draw the link between My Absolute Darling and A Little Life: two books, both alike in indignity. Yanagihara’s novel, in particular, is emerging as the literary benchmark for a hyper-real aesthetics of immersive, bodily-anchored trauma. It’s an aesthetics we are under increasing cultural pressure to consume, to valorise for its brutal honesty, or, perhaps more accurately, its honest brutality.

As I researched this essay, every person I spoke to – trauma professionals and survivors, cultural historians, literary critics, readers, and writers – began our conversation, unprompted, by pointing me to an example of popular contemporary art (books, film, and peak television) that felt performatively, punitively cruel – stories anchored in what the body can stand. Most often mentioned was the second season of The Handmaid’s Tale, which was universally described in the language of moral obligation: viewers steeling themselves to do their televisual homework, their cultural duty. It’s an aesthetic we have a duty to question.

How did we get here? How did trauma become our literary watchword? How did staring down (or at) suffering become synonymous with authorial heroism, and a cultural virtue? And what does it mean to read – to simultaneously consume and bear witness – in an era of beautiful (or beautified) pain? Many of these questions are unanswerable. They should still be asked. They should have been asked a decade ago.

There was never much impetus to look beyond a two-dollar pop-psychology explanation for why misery literature resonated. It was the purview of bored housewives and masochistic mothers, and – it was widely implied – men who couldn’t be trusted with children (‘Can they be certain there isn’t a degree of uncomfortable prurience, or worse, at the relish with which such tales are whisked off the shelves?’ Addley asked in 2007). It was a pornography of suffering: impure and simple.

But there is nothing simple about pornography.

Krissy Kneen (photo by Anthony Mullins)I talk to Krissy Kneen, whose ethically questing and questioning novel An Uncertain Grace (2017) was nominated for the 2018 Stella Prize. She’s also the author of a heady back catalogue of boundary-pushing erotica: ‘I think pornography is a really problematic word to use because it’s completely culturally dependent,’ Krissy explains. ‘What one person or culture considers pornographic, another doesn’t.’

Krissy Kneen (photo by Anthony Mullins)I talk to Krissy Kneen, whose ethically questing and questioning novel An Uncertain Grace (2017) was nominated for the 2018 Stella Prize. She’s also the author of a heady back catalogue of boundary-pushing erotica: ‘I think pornography is a really problematic word to use because it’s completely culturally dependent,’ Krissy explains. ‘What one person or culture considers pornographic, another doesn’t.’

We discuss how ‘trauma porn’ – the term I initially turned to, fuming away in my phosphorescent skeleton – is a lazy rhetorical shorthand for discomfort and antipathy, a way to deflect a question of value by turning it into a question of values: ‘We close off conversations by calling them pornographic,’ Krissy tells me. ‘It means that we’re not supposed to engage unless it’s underhanded or in secret. That’s a problem because it doesn’t allow us to even question what we consider acceptable, or to face social complexities.’

Yanagihara has been candid about constructing A Little Life to stretch the social borders of acceptability. In an interview with the Guardian, she describes her relationship with excess:

One of the things my editor and I fought about is the idea of how much a reader can take ... I wanted there to be something too much about the violence in the book, but I also wanted there to be an exaggeration of everything, an exaggeration of love, of empathy, of pity, of horror. I wanted everything turned up a little too high. I wanted to feel a little bit vulgar in places. Or to be always walking the line between out-and-out sentimentality and the boundaries of good taste. I wanted the reader to really press up against that as much as possible and if I tipped into it in a couple of places, well, I couldn’t really stop it.

It’s an extraordinary statement of artistic intent – one that denies easy purchase for accusations of gratuitousness or narrative preposterousness by reaching for them, luxuriating in them, establishing them as matters of principle. In many ways, it is the logical aesthetic extension of the fiction of ‘radical pessimism’ that emerged alongside mis-lit (Cormac McCarthy’s The Road [2006], Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go [2005], Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin [2003]), a pigeon pair to the rise of the dystopia.

Daniel MendelsohnWriting in the New York Review of Books, author Daniel Mendelsohn voiced fierce objection to the abjection of A Little Life and its seemingly wilful authorial punitiveness – a raft of critical dissent in an ocean of adulation. ‘The abuse that Yanagihara heaps on her protagonist is neither just from a human point of view nor necessary from an artistic one,’ he argued. Yes, Yanagihara would seem to reply. Exactly.

Daniel MendelsohnWriting in the New York Review of Books, author Daniel Mendelsohn voiced fierce objection to the abjection of A Little Life and its seemingly wilful authorial punitiveness – a raft of critical dissent in an ocean of adulation. ‘The abuse that Yanagihara heaps on her protagonist is neither just from a human point of view nor necessary from an artistic one,’ he argued. Yes, Yanagihara would seem to reply. Exactly.

The twin anaesthetising blights of our age of 24-hour media – desensitisation and compassion fatigue – are an obvious starting point in explaining this ‘turn it up to eleven’ approach, but they’re a wholly unsatisfying end point. While they might help explain a general and generalised ratcheting of violence, they fail to address the peculiar quality of that violence in our literature – its immersion in intimate, interpersonal cruelty. For what’s new about this aesthetic isn’t that it includes graphic depictions of suffering, but that it is driven by them. Trauma is not tendered in service of the narrative, it is the narrative.

A Little Life tracks the post-collegiate lives of four men – three of them gay – in New York City through the late 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s; a shared trajectory from youthful dreaming to professional striving to middle-aged affluence. But they exist in a world that has the ethereal self-containment of a fairy tale. There is no AIDS crisis, no Gulf War, no Clinton impeachment. These are men who live at the epicentre of 9/11, and its era-making cultural and geo-political turmoil leaves them entirely unscathed. What’s left is how the men feel about themselves and each other, played out against a backdrop of high-cultural opulence and social largesse – beautiful spaces, beautiful meals, beautiful things, and beautifully ugly pain. It’s a vacuum-sealed universe, insulated and insular; planets orbiting the pitiless sun of Jude’s trauma.

What’s new isn’t what’s present, it’s what’s missing.

My Absolute Darling creates the same sense of allegorical displacement, a world pulled out of time. But here the consumerist gloss of New York City is replaced by the Thoreauvian poetry of the natural world. Turtle exists in a kind of narrative terrarium – a place of seed-pods, critters, and loam – the crenulations of a leaf described with all the rhetorical grandeur of a cathedral. As in A Little Life, both the engine and edges of the story are the ways in which she is hurt.

Again, it’s a purposeful aesthetic. In an interview with the National Book Foundation, Yanagihara explains:

I wanted to remove every external event from this book: once you remove historical landmarks from a narrative, you force the reader into a sort of walled space, one in which they have no choice but to focus entirely on the interior lives of these characters. There’s no distraction and no respite and no tether, either: I wanted the world of this book to feel by turns intimate and oppressive – and utterly inescapable.

‘You could have everything in this book the way it is – the descriptions of the self-cutting, the childhood of abuse – that’s not the problem,’ Daniel Mendelsohn argues. This is the problem – this wilful hermeticism, and its underlying assumption that the graphic description of trauma is necessary and sufficient to understand it. ‘The literature of suffering has a long and honourable history,’ he explains, ‘what’s interesting is for an author to show so little interest in evoking any quality in their characters except their capacity for suffering.’ It takes historical imagination – historical memory – to make sense of suffering, to see it as contingent and explicable rather than simply inevitable.

I called Daniel Mendelsohn in New York to talk about his review of A Little Life (a review so forceful in its ethical opprobrium that – unusually, extraordinarily – the novel’s editor, Gerald Howard, wrote an open letter in the book’s defence). The atomised aesthetic of A Little Life still troubles Mendelsohn. ‘Something very interesting is taking place socio-culturally, and it does need to be unpacked.’

Mendelsohn posits that it was the US television talk shows of the 1970s and 1980s – the living-room confessionals of Phil Donahue, Jerry Springer, and Oprah Winfrey – that prepared the literary ground:

I think it’s not accidental that within five to ten years of these shows becoming popular, memoirs started to emerge as a dominant literary genre. They go back to St Augustine, of course, but they’ve been revived in an interesting way. There’s been a cultural trend toward the valuation of suffering and trauma as a positive element of the life story, because the applause one receives is directly proportional to the amount one has suffered.

The conflation of bravery and openness stands in marked opposition – arguably in backlash – to the post-World War II culture of buried horrors. That generation’s silence neither negated nor devenomised their traumas. To the contrary: ‘I was brought up in a community where the collective trauma wasn’t the elephant in the room, it was the room,’ explains Bram Presser, author of the multi-award-winning The Book of Dirt (2017), a novel that braids the narrative techniques of memoir and fable to explore his grandparent’s Holocaust survival. ‘Trauma was the structure itself, the surrounds.’

Bram Presser, author of The Book Of Dirt

Bram Presser, author of The Book Of Dirt

‘The science is in on this,’ Krissy Kneen tells me, emphatically, as she explains the research that underpins her current writing project: a novelistic reckoning with untold family stories and fables. ‘We know that trauma plays out in the body. We know that traumatic events on a body cause epigenetic change which gets passed down generation to generation. We know these things.’

We are certainly learning. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was not formalised as a psychological diagnosis until 1980, after lobbying from Vietnam veterans. In 1986 the psychologist Paul-Lees Harvey said ‘if mental disorders were listed on the New York Stock Exchange, PTSD would be a growth stock to watch’.

In the last three decades we have been furnished, not only with a diagnostic framework for trauma, but – vitally – with a lexicon that carries the authoritative heft of medicalisation, a lexicon that has proved so resonant that it has broken free of its pathology and soaked into the cultural Zeitgeist. Trauma now risks explaining everything and nothing; meaning everything and nothing.

Consider the words that readers on Goodreads use to describe their experience of A Little Life and My Absolute Darling: inescapable, distressing, unsettling, disorienting, destroying, wrenching, dehumanising; this is the experiential language of trauma.

A Pan Macmillan advertisement for A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

A Pan Macmillan advertisement for A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

I listen to Bram Presser explain how carefully he penned his novel, ever vigilant to the lure of beautifying, or wallowing in, the horrors of the most monstrous of twentieth-century traumas: ‘It was very much at the forefront of my mind not to become gratuitous,’ he tells me. ‘I wanted to give back dignity and agency to the people in the [concentration] camps. I feel like that gets lost a lot in trauma narratives – people either try and make absolute heroes or absolute victims.’

But Presser acknowledges that – as a third-generation survivor – he was anchored to history, to images that have been burned into our collective consciousness; walking in the storytelling footsteps of those who walked behind Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel: ‘I think if you tell an ordinary life and experience, knowing that people already know what’s going on around it, there’s no need to augment it with atrocity,’ Presser explains. ‘The atrocity is already there, waiting.’

What is emerging is a political climate – a political economy – in which we increasingly understand that trauma is not catastrophe-bound, not limited to wars and massacres and hijacked planes, but a part of everyday life. Perniciously banal and too-often systemic. Trauma isn’t just Port Arthur, it’s #MeToo.

The threat isn’t ‘out there’ anymore, it’s ‘right here’ – in our houses, offices, schools, churches, police stations, and prisons, in the hearts of the people who are meant to care about, and for, us. ‘The idea of institutionalised abuse inflicted ... by figures of trust is very much the nightmarish mythology of our times,’ writes Guardian journalist Tim Adams. Surely it is no accident that one of the most robust early markets for misery memoirs of child abuse was Ireland.

In Mendelsohn’s infamous review, he posited:

Many readers today have reached adulthood in educational institutions where a generalised sense of helplessness and acute anxiety have become the norm; places where, indeed, young people are increasingly encouraged to see themselves not as agents in life but as potential victims: of their dates, their roommates, their professors, institutions and history in general ... confirming the pre-existing view of the world as a site of victimisation and little else.

What Mendelsohn is describing is not a culture of oversensitivity as much as of hypersensitivity: a milieu generations of geopolitical trauma in the making. Parents from the duck-and-cover 1960s raising risk-aware children, who stood at the threshold of adulthood on 9/11 and are now raising their children to save a planet. It is a culture that is not just trauma literate, but traumatised.

‘It’s interesting, in a culture that is endlessly talking about power and empowerment,’ Mendelsohn ponders, ‘that the genre that seems to be rising are fictions of disempowerment.’

It sounds paradoxical, but it makes perfect sense. Fear may have bred hyper-sensitivity, but its obverse is outrage; both are the products of vigilance. Western culture is tuned to the note of harm: alert to its mechanics, aware of its corrosive impact. Younger generations are also increasingly willing and able to call it by its name and energised to confront its effects. Whether those confrontations will prove productive is up for debate, but it is hard to fault a generation who care so deeply – so openly – about not hurting people.

Sarah Krasnostein's book The Trauma Cleaner, winner of the Victorian Prize for Literature, 2018 and the ABIA General Non-Fiction Book of the Year, 2018 Consider the new-release shelf of any half-decent Aussie bookstore: there’s Leigh Sales’s Any Ordinary Day (2018), which draws hope from the worst days of our lives; Sarah Krasnostein’s profoundly empathetic The Trauma Cleaner (2017); and Bri Lee’s incendiary Eggshell Skull (2018); there’s When Elephants Fight (2018), Majok Tulba’s visceral new novel of South Sudanese refugees; Kim Scott’s reckoning with Australia’s bloody history in Taboo (2017); and, of course, Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains (2018), an account of trauma that’s shamefully Australian-made. Personal, familial, generational, historical, cultural, and political: there is nothing furtive about our literary relationship with trauma in 2018. We’re looking it squarely in the eye. Staring it down.

Sarah Krasnostein's book The Trauma Cleaner, winner of the Victorian Prize for Literature, 2018 and the ABIA General Non-Fiction Book of the Year, 2018 Consider the new-release shelf of any half-decent Aussie bookstore: there’s Leigh Sales’s Any Ordinary Day (2018), which draws hope from the worst days of our lives; Sarah Krasnostein’s profoundly empathetic The Trauma Cleaner (2017); and Bri Lee’s incendiary Eggshell Skull (2018); there’s When Elephants Fight (2018), Majok Tulba’s visceral new novel of South Sudanese refugees; Kim Scott’s reckoning with Australia’s bloody history in Taboo (2017); and, of course, Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani’s No Friend but the Mountains (2018), an account of trauma that’s shamefully Australian-made. Personal, familial, generational, historical, cultural, and political: there is nothing furtive about our literary relationship with trauma in 2018. We’re looking it squarely in the eye. Staring it down.

This is the context in which we must understand the emerging literary aesthetic of A Little Life and My Absolute Darling: they’re not trying to explain or rationalise trauma, but to simulate its sense of suffocation, inhabit its elemental physicality. Trauma: body and soul.

There is an argument to be made that stories like these are profoundly necessary: to challenge taboos; confront and counter damaging social myths and scripts (in particular, the script of stoic redemption and recovery); to seek consolation and insight; to spark empathy and compassionate connection. The quiet dignity of bearing witness. A vital addition to a conversation in which the body – especially the traumatised body – has so often been squeamishly absent.

Ubiquity will diminish the argument for necessity – it will certainly raise the ethical bar. As more of these novels emerge, we must ask what they are asking of us. We increasingly understand the cultural and therapeutic power of narrative – of who tells a story and how. As writer Tom McAllister pithily notes: ‘there is a human cost, not just to the victims, but to our culture in general ... writers have a moral obligation to avoid infecting the universe with more careless storytelling.’

But while we are in the midst of a passionate cultural conversation about the ethics of authorship (much of which is really a conversation about the difference between good and bad art), we seldom speak of the ethics of readership. We must also ask ourselves what we are seeking in what we read.

Reflecting on the rise of memoir in The New Yorker in 2010, Mendelsohn argued: ‘the truth we seek from novels is different from the truth we seek from memoirs. Novels, you might say, represent “a truth” about life, whereas memoirs and nonfiction accounts represent “the truth” about specific things that have happened.’ Our attraction to novels of baroque suffering is therefore likely to say far more about what we want for ourselves, than about what trauma survivors, and the public discussion about trauma, need.

Those wants bear interrogating, particularly when we compare the widespread critical acclaim My Absolute Darling’s lushly rendered violence against a fictional woman has received, against the reception first-person accounts routinely receive, regardless of their artfulness, the mis-lit taint of unseemly self-exposure.

It is hard to take a clear-eyed look at why we are compelled by pain (frequently the pain of women and children), and what we signal about ourselves and our culture when we champion fiction that performs it. For even if empathy does work exactly the way we wish it to, it does not preclude pleasure. And there’s so little to separate empathy from pity; honesty from fetish. There is power in watching.

Are these novels the literary equivalent of ‘slacktivism’, as Krissy Kneen suggests? ‘The reader isn’t required to do anything except feel outrage and there’s something about that that is similar to the way we now participate in society by just shooting off a Facebook post or a tweet and thinking “okay I’ve done my bit” for the cause.’ Are they a way of avoiding the banal horrors of the everyday: looking at the sun, so as to avoid having to look at the ground? Are they a form of personal benchmarking: a way to find comfort through downward comparison in a world that feels overwhelming and drowned in sorrow? The literary equivalent of poverty tourism? Or are they a modern form of defeatist catharsis in which, in a godless world, suffering is neither proportionate nor earned (as it is in Greek tragedy), but simply inevitable? Cultural self-flagellation.

After a particularly violent encounter in Tallent’s novel, Turtle’s father explains his philosophy of pain:

The idea, so say the philosophers, is that you sit yourself down across from someone, and begin breaking his fingers with a hammer. You see how he reacts. He screams. He clutches his hands to his chest. You infer that he acts this way because he is in pain. But what really happens, when you are face-to-face and someone in pain, what really happens is that the gulf between you and them is made apparent. Their pain is utterly inaccessible to you. It might as well be pantomime.

Emotional pantomime, or engine of empathy? These books are the ultimate stress tests of this question; they pull the focus in tight, break their narrative hammers over their protagonists’ bodies, and ask us what it is we really feel. As readers, this is not a comfortable question to ask or answer. It’s not a comfortable critical space to enter, either, with its lurking potential for moral judgement. But, as a friend wisely said to me, ‘Trauma is pretty fucking uncomfortable.’

Beejay Silcox (photo by Elizabeth-Richelle Photography)As a reader and critic, my fiercest objection to the narrative aesthetic of A Little Life and My Absolute Darling is simply that it demands so little of me, other than my endurance – their walled spaces seem to insulate rather than illuminate. Krissy Kneen concurs: ‘Books come into their own where they’re a conversation between a writer and a reader,’ she explains. ‘These books don’t leave any space for a reader to become an active participant ... it’s really clear what’s wrong, and it’s really clear what’s right, and we don’t have to make the kind of decisions that we really should be making in real life – asking why people behave in particular ways, and looking for complexity in that behaviour.’

Beejay Silcox (photo by Elizabeth-Richelle Photography)As a reader and critic, my fiercest objection to the narrative aesthetic of A Little Life and My Absolute Darling is simply that it demands so little of me, other than my endurance – their walled spaces seem to insulate rather than illuminate. Krissy Kneen concurs: ‘Books come into their own where they’re a conversation between a writer and a reader,’ she explains. ‘These books don’t leave any space for a reader to become an active participant ... it’s really clear what’s wrong, and it’s really clear what’s right, and we don’t have to make the kind of decisions that we really should be making in real life – asking why people behave in particular ways, and looking for complexity in that behaviour.’

That’s my objection to our politics too, its retreat to corners, to the monochromatic didacticism – the historical amnesia – of fairy tales. How the focus on extremes distracts us from the system that breeds them. ‘Sometimes books come along that match the times,’ wrote a critic of A Little Life. That’s so very true.

The complexity these novels do bring is the exquisite pain of beauty – the monstrously sublime and the sublimely monstrous. It’s this aesthetic of aesthetised pain, punitiveness bordering on fetishisation, that prompted Mendelsohn to write: ‘Yanagihara’s novel has duped many into confusing anguish and ecstasy, pleasure and pain.’ And it was the implication of authorial dishonesty that prompted her editor to retort: ‘At bottom Mendelsohn seems to have decided that A Little Life just appeals to the wrong kind of reader.’

'I have strong feelings about this because of my Holocaust writing experience,’ Daniel Mendelsohn explains. ‘You know you are in a very dangerous territory when you are taking the suffering of people and turning it into a narrative which people inevitably are going to take some kind of pleasure from, even just the pleasure of reading a good story.’

It’s hard to disagree. And yet I am haunted by the censorious danger I feel in calling it danger. As far as I’m able to give an intellectual shape to my discomfort, I think this is it.

‘Criticism is an inherently moral undertaking,’ Mendelsohn assures me as we wrap up our call. ‘It starts with creation, with separating light from dark.’

It was hard to tell the difference when my bones were glowing. It’s still hard.

Comments powered by CComment