- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

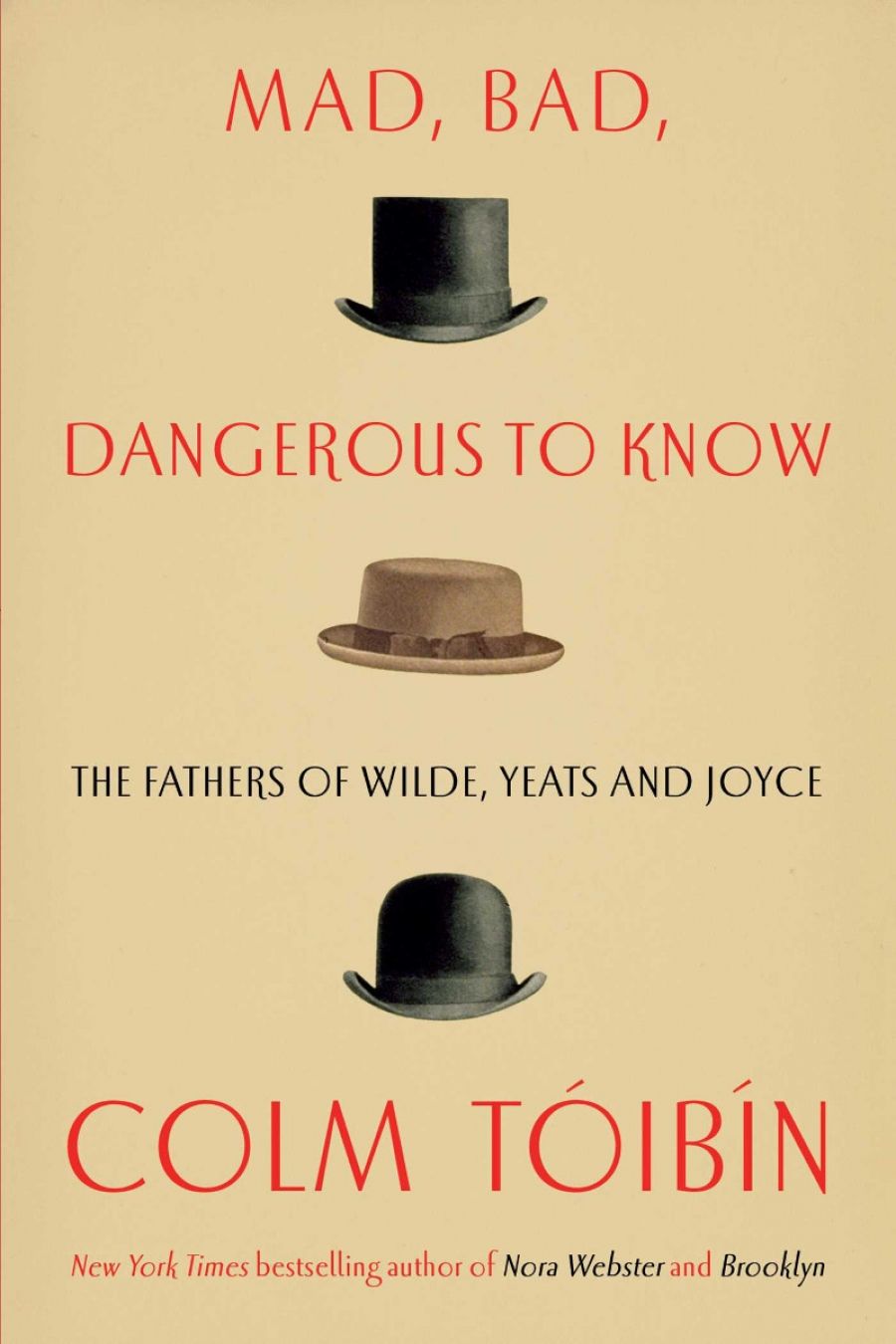

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson reviews 'Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know: The fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce' by Colm Tóibín

- Custom Highlight Text:

Like so many parents of great authors, the fathers of Oscar Wilde, W.B. Yeats, and James Joyce have much to answer for. Certainly, each man had a profound influence on his son’s literary career without for a moment being conscious of the literary consequences of his words and actions ...

- Book 1 Title: Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know

- Book 1 Subtitle: The fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $29.99 hb, 192 pp, 9781760781149

In addition to the pleasure we anticipate from reading his words on any topic, Colm Tóibín demonstrates in this short, illuminating book a wonderful capacity for empathy, as well as an acute understanding of the creative process. In exploring the extent to which each writer, for better or worse, was his father’s son, this book continues the enquiry into the relationship between writers and their families that began in Tóibín’s essay collection New Ways to Kill Your Mother: Writers and their families (2012).

It is a consequence of their canonical status that there has been so much biographical and scholarly interest in the families of Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce. In each case, it was by no means predestined that the son would become a famous and influential writer. Just being an Irish writer at that time could be expected to entail provincial obscurity.

With the exception of Sir William Wilde, an eminent surgeon specialising in the eye and the ear, none of the fathers provided a role model for the attainment of professional success. In the case of Yeats and Joyce, the son had to discover within himself the confidence and industry lacking in the father. Joyce’s father was a medical student who dropped out of his course, while Yeats’s father qualified as a lawyer but didn’t practise. Yeats’s father became a painter prone to procrastination, preferring to talk about the portraits he was working on rather than finish them. John B. Yeats presided over a family that grew at the same time as the income from the property he had inherited shrank. Guilt at the knowledge of the poverty he inflicted on his wife, who ‘had believed she was marrying a man who was likely to become a prominent barrister or judge’, only made things more difficult for John B. Yeats psychologically.

‘While their father’s financial circumstances worsened, all four of the Yeats children worked and made money. From early on in their lives, they were serious, determined and industrious.’ Yeats’s younger brother Jack became a successful painter, his sister Lily a leading embroiderer, and the fourth sibling, Elizabeth, was an educator and publisher. By the age of thirty, W.B. Yeats had generated a long list of publications, including seven books.

Yeats viewed his father critically in terms of personal shortcomings but absorbed his aesthetic ideas. In one letter to his father, Yeats wrote of how he had realised ‘with some surprise how fully my philosophy of Life has been inherited from you in all but its details and applications’.

Yeats’s father was a poor provider, though far from a domestic tyrant. In contrast, Joyce’s father was abusive towards his wife and children, drank excessively, and pretty much failed at everything – though he was a good talker. ‘It would be easy,’ writes Tóibín, ‘to consign John Stanislaus Joyce to the position of one of the worst Irish husbands and worst Irish fathers in recorded history.’ And while James’s younger brother Stanislaus did just that in his family memoir, the older sibling engaged in a less antagonistic way with their father’s dubious legacy. ‘Instead of actively and opening killing his father, James Joyce sought not only to memorialise his father but also retrace his steps, enter his spirit, use what he needed from his father’s life to nourish his own art.’

In the case of Wilde and his father, at the heart of the matter is the instability of the family’s social position as members of the Anglo-Irish professional élite, ‘a strange, unruly ruling class in Ireland, not accepted as fully Irish and not wealthy landowners either’. Neither English nor Irish, the small social circle to which the Wilde family belonged in Dublin was characterised by scandal and transgression. ‘No one was ever sure what they believed in, where their loyalty lay. It was fragile, wavering, open to suggestion, and open also to pressure.’

Oscar Wilde, John Keats, and James Joyce

Oscar Wilde, John Keats, and James Joyce

‘What is fascinating is how the duality of their position made its way into the sexual realm,’ writes Tóibín, describing how the scandal surrounding the always precarious relationship between Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas was prefigured by Sir William’s infidelities, which resulted in more than one child being born outside marriage and, in a direct parallel with his son’s downfall, in a disastrous legal attempt to stop a younger lover from stalking him and his wife, which resulted in public disgrace. According to Tóibín, the impact that Sir William had on his son is felt most poignantly in the absence of direct references to him in Oscar’s work. The silence seems loudest of all in his prison memoir De Profundis, as Tóibín notes: ‘While Wilde had time to say everything he needed to say, there is one figure missing from the pages of his letter, a figure whose life has a considerable number of similarities with that of Wilde himself.’

Ultimately, the presence of these three Irish fathers was too pervasive to have been fully delineated by their sons. It could be that none of us ever quite comes to terms with our parents, though we may spend a lifetime attempting to do so.

Comments powered by CComment