- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

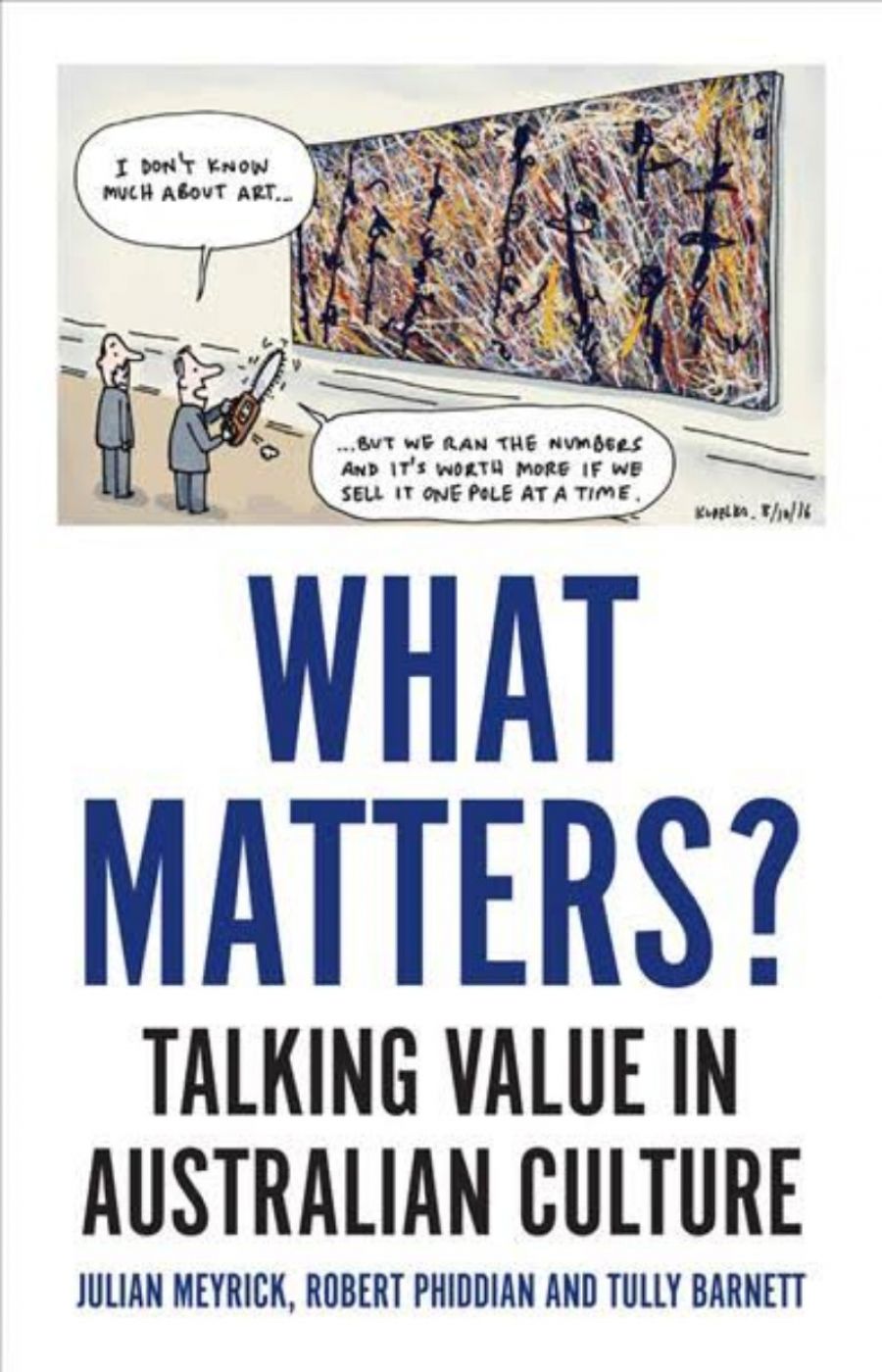

- Custom Article Title: Gabriella Coslovich reviews 'What Matters? Talking value in Australian Culture' by Julian Meyrick, Robert Phiddian, and Tully Barnett

- Custom Highlight Text:

As I sat down to write this review, a media release popped into my email inbox with the excited news that more than 400,000 people had visited the National Gallery of Victoria’s MoMA exhibition over its four-month duration, making it the NGV’s ‘second most attended ticketed exhibition on record ...

- Book 1 Title: What Matters?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Talking value in Australian Culture

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $24.95 pb, 192 pp, 9781925523805

‘Exhibitions like this are among the top reasons tourists are flocking to Victoria,’ the minister said. Last year, ‘cultural tourism’ had injected two billion dollars into the state’s economy, an eighty-eight per cent increase from 2013, a trend that was set to continue. The exhibition’s value was framed wholly through the lens of its economic benefit, with the underlying assumption that ever-growing crowds of ‘cultural tourists’ were a good thing. Not that one wishes to smugly condemn the NGV, or the minister, for flaunting the figures. Numbers make headlines. They are easily digested, easily relayed to a busy newsroom editor (they look as straightforward as sporting results), and they appease political masters, making the case for arts funding at a time when neo-liberalism degrades life to a dollar sign. But what do they tell us about the exhibition itself? The merits of its thesis? The quality of the art on view? The way it might have changed someone’s life in a quietly significant way? Its effect on civic well-being? Nothing.

The email was a timely illustration of the tendency to reduce the value of the arts to a set of numbers – an inclination that authors and Flinders University academics Julian Meyrick, Robert Phiddian, and Tully Barnett rail against in their book What Matters? Talking value in Australian culture. ‘When did culture become a number?’ they ask in their punchy introduction, launching a much-needed public debate. When a cultural landmark such as the Sydney Opera House is vulnerable to the defilement of advertising, this is a discussion we sorely need to have.

The authors aim to ‘change the conversation around the evaluation of culture in all domains, but especially the government one, so that it reflects more context, is more honest, and makes more sense’. Their book addresses those who are ‘seriously interested in the value of arts and culture’, including artists, critics, board members, policy makers, managers of cultural organisations, philanthropists, and government leaders of cultural programs, and urges them to resist ‘the language of government’, or, as it also referred to on several occasions, the language of ‘bullshit’.

NGV promotional material advertising 400,000 MONA attendants

NGV promotional material advertising 400,000 MONA attendants

Worthy objectives. However, if you set out to write a book proposing a better way to talk about the value of art, it should be well written. You cannot prize the plain-speaking recommended by Don Watson in his marvellous book Death Sentence (2003) and then fail to heed the master’s advice (I doubt Watson would care for the phrase ‘blue skies thinking’).

For the most part, What Matters? is an absorbing – and quirky – read as it challenges the rise of ‘metric power and questions the validity of metaphors such as ‘the marketplace of ideas’, the myth of endless growth, buzz words such as ‘excellence’ and ‘innovation’, and what government budgets refer to as the ‘cultural function’.

It’s a shame that at times the authors shrink from their commitment to plain speaking and engage in precisely the type of ‘anaesthetising writing’ that Watson (via George Orwell) laments. This lapse is particularly evident in the chapter that introduces the (admittedly complex) concepts of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and Integrated Reporting (IR), new styles of corporate reporting that the authors suggest the cultural sector might look to as examples of ‘holistic evaluative systems designed to focus thinking on what matters’, which value more than just financial return. IR, we are told, puts ‘great stress on connectivity between different types of information, and value–generation over time’: ‘Connectivity is a function of simplicity and concision, and this is a pain point for a framework that aims to produce one report that overarches any others an organisation might generate.’ Watson might set the above sentence as an exercise, with the instruction to rewrite it in plain English.

Julian Meyrick, Tully Barnett, and Robert Phiddian

Julian Meyrick, Tully Barnett, and Robert Phiddian

The book’s strength lies in its topicality, in its challenge to the ‘metric tide’, as Meyrick neatly put it during an interview on ABC Radio National recently, that is flooding our lives.

‘At what point,’ the authors ask, ‘do we stop trying to measure something and try to understand it better? What would this involve, exactly, if we were to do it?’ Oddly enough, it’s Christ’s knack for telling parables that is held up as a model. ‘Parables of value’, the authors propose, are meaningful ways of getting the message across about culture’s utility in the broadest sense. They present three examples of their own: a parable about the oscillating popularity of Patrick White’s plays and what box-office figures don’t tell you; another about the threat posed to the arts and culture by global tech giants; and a third about the importance of the humbly resourced Adelaide Festival of Ideas.

If you are looking for a guide on avoiding so-called bullshit language, Death Sentence or Gilda Williams’s How to Write About Contemporary Art (2014) are good options. The value of this book is in its provocative declaration that there is a problem in the way we assess the arts and its ideas for new ways of thinking.

Comments powered by CComment