- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

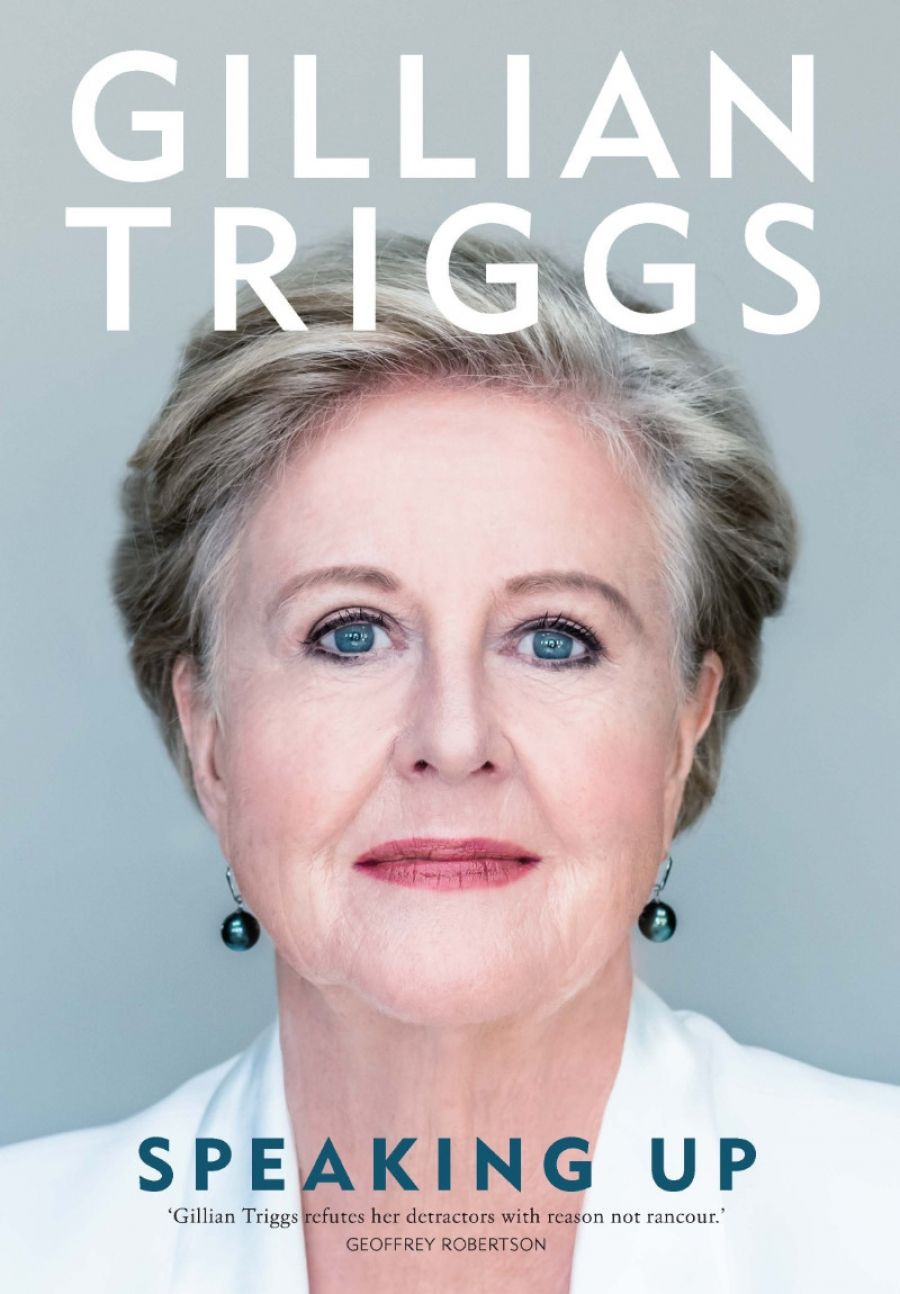

- Custom Article Title: Jane Cadzow reviews 'Speaking Up' by Gillian Triggs

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gillian Triggs is a pearls-and-perfectly-cut-jacket person these days, so it is thrilling to learn that she was dressed head to toe in motorcycle leathers when she had one of the more instructive experiences of her life. It was 1972, and Triggs, the future president of the Australian Human Rights Commission ...

- Book 1 Title: Speaking Up

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $45 hb, 300 pp, 9780522873511

Triggs was reminded of that incident on a warm night in central Sydney more than forty years later. Leaving the Human Rights Commission office on Pitt Street, she was approached by three Indigenous people who had just attended one of the regular talks held by the Commission. They asked if she would help them get a taxi. Triggs was puzzled: a cab rank, with several taxis lined up, was right in front of them. When the three told her that no driver would take them to their apartment, Triggs said confidently: ‘Come with me.’ As she and the trio settled into the first cab, the driver ordered them to get out. The next driver did the same. Not until the third taxi did they find a driver who was happy to have them as passengers.

This book, published a year after Triggs completed her turbulent five-year term as the Commission president, is in part a lament. Overt racism is on the rise in this country, she says, and that is just one aspect of the blight that afflicts us. Australia was one of the architects of international human rights agreements after World War II and has a history of being a good global citizen. But it seems to Triggs that in the twenty-first century something has gone terribly wrong. She asks how we lost our collective courage and compassion, becoming a nation willing to accept the imposition of unnecessarily draconian counterterrorism laws, for instance, and prepared to turn a blind eye to the indefinite detention of asylum seekers in cruel conditions.

In February 2015, Triggs released a damning report, The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention. It detailed the impact of prolonged imprisonment on asylum seekers’ children. Tony Abbott, then prime minister, called it a ‘transparent stitch-up’. Triggs had become a polarising figure, relentlessly criticised by right-wing politicians and Rupert Murdoch’s stable of columnists, while lauded by others for coolly sticking to her principles and doing her job. She makes clear that she would have preferred to stay out of the headlines. ‘I was not looking for controversy,’ she says on page one. ‘It found me.’

Triggs was born in London in 1945. Her father, Richard, was a tank commander in North Africa during World War II; her mother, Doreen, served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service. The family moved to Australia when Triggs was only twelve, but as we know from her frequent media appearances, she has retained more than a trace of a posh English accent. In print, as in person, she has an air of calm authority and a certain well-bred steeliness. Her sentences are clear and crisp. Her tone is pleasant but firm. She tells us that she inherited her sense of social justice from her parents, who talked of freedom, non-discrimination, and racial equality as the values for which the war had been fought.

A young Gillian Triggs ready to work at one of her first jobs as a waitress at a seafood restarauntAfter studying law at the University of Melbourne, Triggs won a scholarship to do a postgraduate degree in international law at Southern Methodist University in Texas. The job with the Dallas Police Department helped finance her studies. Before landing it, she worked part-time as a waiter in a seafood restaurant, wearing an abbreviated sailor suit complete with white shorts, white boots, and a jaunty white cap. (Sportingly, she includes a photograph.) Back in Melbourne, she worked on a PhD thesis on territorial sovereignty and married Sandy Clark, then dean of University of Melbourne’s law school. The couple had three children in less than four years. The youngest, Victoria, had a rare genetic disorder called Edwards’ syndrome. Triggs says she eventually decided that giving adequate attention to two toddlers and a baby with profound disabilities was not possible. Five-month-old Victoria was placed with a foster family who provided her primary care until she died at the age of twenty.

A young Gillian Triggs ready to work at one of her first jobs as a waitress at a seafood restarauntAfter studying law at the University of Melbourne, Triggs won a scholarship to do a postgraduate degree in international law at Southern Methodist University in Texas. The job with the Dallas Police Department helped finance her studies. Before landing it, she worked part-time as a waiter in a seafood restaurant, wearing an abbreviated sailor suit complete with white shorts, white boots, and a jaunty white cap. (Sportingly, she includes a photograph.) Back in Melbourne, she worked on a PhD thesis on territorial sovereignty and married Sandy Clark, then dean of University of Melbourne’s law school. The couple had three children in less than four years. The youngest, Victoria, had a rare genetic disorder called Edwards’ syndrome. Triggs says she eventually decided that giving adequate attention to two toddlers and a baby with profound disabilities was not possible. Five-month-old Victoria was placed with a foster family who provided her primary care until she died at the age of twenty.

Triggs covers Victoria’s life and death in a couple of subdued paragraphs while devoting an entire chapter to the rancorous public debate over the pros and cons of section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act (1975). Billed as a memoir, Speaking Up only just qualifies as such: it is more a dissertation on human rights, politics, and the law than it is a study of Triggs herself. Large chunks of the book will seem pretty dry to readers expecting insights into the character of this formidable woman. Triggs includes a few good anecdotes and allows us occasional glimpses of emotion – the tears in her eyes when she visited the Christmas Island immigration detention centre – but on the whole she keeps up her guard, supplying only the bare bones of a biography.

Gillian Triggs marrying Alan Brown in Singapore in 1992Since 1992, Triggs has been married to Alan Brown, a senior diplomat she accompanied to foreign postings. It is an indication of her grit and ambition that being the ambassador’s wife did not stop her from carving out her own distinguished career. By the time she accepted the presidency of the Australian Human Rights Commission in 2012, she had written legal textbooks, headed the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, and been dean of University of Sydney’s law school.

Gillian Triggs marrying Alan Brown in Singapore in 1992Since 1992, Triggs has been married to Alan Brown, a senior diplomat she accompanied to foreign postings. It is an indication of her grit and ambition that being the ambassador’s wife did not stop her from carving out her own distinguished career. By the time she accepted the presidency of the Australian Human Rights Commission in 2012, she had written legal textbooks, headed the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, and been dean of University of Sydney’s law school.

When people ask how Triggs withstood the abuse she incurred as the nation’s chief defender of human rights, she writes that she tends to refer cheerfully to a gin and tonic and a supportive husband. But I wanted a better explanation than that. I finished the book knowing that Australia is the only democratic nation in the world without a bill or charter of rights to ensure the freedoms of its citizens, and that Triggs strongly believes it is time we got one. I know Triggs’s opinion on many things, in fact. But, to my regret, I don’t really know Gillian Triggs.

Comments powered by CComment