- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Maggie MacKellar reviews 'You Daughters of Freedom' by Clare Wright

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Clare Wright’s new history, You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians who won the vote and inspired the world, landed in my mailbox, I opened it with some trepidation. It was big, a fact I now realise I should have expected but nevertheless a somewhat disheartening one – arriving as it did at the beginning of our lambing season on the farm. It sat on the kitchen table, slightly out of place beside tractor catalogues, long-term rainfall predictions (depressing), and pamphlets advertising ram sales.

- Book 1 Title: You Daughters of Freedom

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Australians who won the vote and inspired the world

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $49.99 hb, 432 pp, 9781925603934

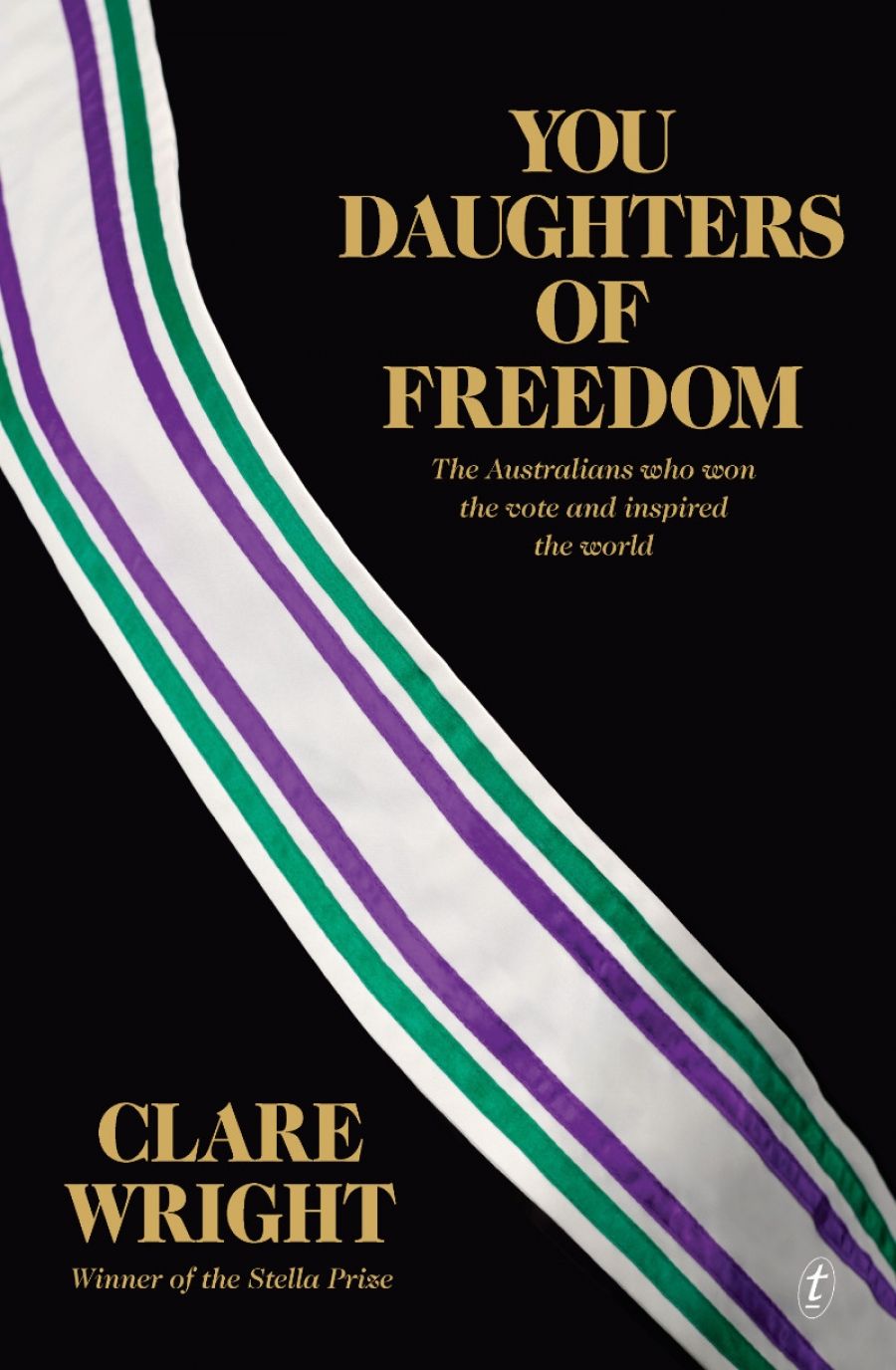

Among the debris, it screamed ‘Important Book’. The cover is brilliant: glossy black with gold lettering, and that inspired title, a phrase of Emmeline Pankhurst’s to Vida Goldstein on her return to Australia in 1922, underlined in an exultant swoop by a photograph of the famous suffragette sash. It’s emblazoned with praise. Senator Penny Wong endorses You Daughters of Freedom as a ‘clarion call’. It’s given a gold star by Anne Summers, Judith Brett, and Clementine Ford – and, lest we forget, a reminder Wright is a past winner of the Stella Prize. It all feels a bit daunting.

On my Tasmanian sheep farm, I’m a long way from the epicentre of feminist politics. I read it through the blur of lambing – early mornings, long days – in tiny snippets of time away from the grind of bargaining with the brutality of nature. When I finish, I want to sweep the table clean of all farming paraphernalia, stand on it, hold the book aloft and and tell every person I know to read it.

Wright starts with an object and a place. She takes us for a walk through the Great Hall, Parliament House, Canberra. We walk past the tapestry designed by Arthur Boyd and woven by fourteen weavers over two years. It represents the Australian landscape in the fibre that brought wealth to a new nation, and hours and hours of women’s labour, for once enshrined and not washed up and left to dry on the draining board. Then we stand in front of the sixteen-metre embroidery designed by Kay Lawrence and ‘wrought by 500 highly skilled women from all over Australia’ (my grandmother being one of them). Further in we go, past portraits of Australia’s prime ministers, the march of time evident through a history of facial hair. Wright, our tour guide, points out governors-general and monarchs. There are only two women thus far. They are Australia’s first female governor-general, Quentin Bryce and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second. Julia Gillard, Australia’s first female prime minister, is yet to be immortalised in oils. Directly opposite the queen, who is dressed in wattle yellow, are the 1963 Yirrkala bark petitions. Already I have a sense of Wright’s ability to see the poetics of politics. Look, there’s Tom Roberts’s The Big Picture (his painting depicting the first sitting of the parliament of the Australian Commonwealth), on permanent loan from the Royal Collection. ‘It’s not easy to own your own history,’ Wright quips. I love it. It’s the ease of commentary, someone comfortable in their own voice. I sign up for wherever we are going.

Dora Meeson Coates, Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done, 1908 (photo via Parliament House Art Collection)We are further in and standing before a glass cabinet display. Here, Wright tells us, is a national treasure, an object both functional and beautiful, one that, until she stood before it in 2014, she had no idea existed. It’s a banner: ‘Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done’. Painted by Dora Meeson Coates (an Australian) in London in 1908, it represents a moment in time when Australian women led the world. I will leave it to Wright to explain Meeson Coate’s radicalism in conceiving and executing such a banner (she does it brilliantly in a stand-alone chapter). But when Wright enquires about the provenance of the banner, she finds little is known beyond the bare facts of its purchase and return. ‘In the thirty years since it “came home”, the banner had become untethered from its remarkable history.’

Dora Meeson Coates, Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done, 1908 (photo via Parliament House Art Collection)We are further in and standing before a glass cabinet display. Here, Wright tells us, is a national treasure, an object both functional and beautiful, one that, until she stood before it in 2014, she had no idea existed. It’s a banner: ‘Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done’. Painted by Dora Meeson Coates (an Australian) in London in 1908, it represents a moment in time when Australian women led the world. I will leave it to Wright to explain Meeson Coate’s radicalism in conceiving and executing such a banner (she does it brilliantly in a stand-alone chapter). But when Wright enquires about the provenance of the banner, she finds little is known beyond the bare facts of its purchase and return. ‘In the thirty years since it “came home”, the banner had become untethered from its remarkable history.’

Wright has her object. In and out we go, swept up by the remarkable connections across time and place. That’s the beauty of this book. It’s an epic told in evocative, readable, triumphant, unflinching snapshots. I tip my hat to Wright’s research network, and she too praises the remarkable gathering of connections. It enables her to cite the particular and to show how it informs an unfolding international drama, with Australian women at its centre. ‘This is the story of how the world’s newest nation became a global exemplar, exporting to the world a model of democracy that was, at once, ahead of its time and perfectly of the moment.’

I almost need a family tree for the first one hundred pages. We meet the five women the history is structured around, and see them in their Australian context. Vida Goldstein, Dora Montefiore, Nellie Martel, Dora Meeson Coates, and (my favourite) the daring Muriel Matters. The detail at times threatens to overwhelm us. But Wright holds it together. Deep winter, February 1903, the Oval Office: I read the scene where Goldstein, leader of the women’s suffrage movement in Australia, meets Theodore Roosevelt, then president of the United States. It’s dramatic enough on its own, but I’m reading it as American women protest the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the United States Supreme Court. I’m reading as women are arrested for opposing the appointment of a man who threatens to take away women’s rights over their own bodies. I’m reading as two women corner Republican Senator Jeff Flake in an elevator and force him to look at them and to see that a culture of rape and sexual assault exists across all levels of US society.

Muriel Matters seated in the window of her caravan during the Womens Freedom League tour in Guildford Surrey, 1908 (photo via Wikipedia Commons)

Muriel Matters seated in the window of her caravan during the Womens Freedom League tour in Guildford Surrey, 1908 (photo via Wikipedia Commons)

I flip back to Wright’s epigraph, a quote from Frederick Douglass in 1857: ‘Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.’

I read of Muriel Matters chaining herself to the metal grille separating the Ladies’ Gallery from parliament, her voice, honed by hundreds, if not thousands of concert hall performances, ringing through the stuffy air of the House of Commons: ‘Votes for Women’. The flat Adelaide vowels and courageous defiance are heavy with meaning. Wright draws it out to full effect. Power concedes nothing without a demand, and Australian women, possessing the franchise as few others did then, demanded the same for their international sisters.

What they didn’t demand were votes for Indigenous women. Race matters in this history. It matters because it is simply not there. Wright doesn’t ignore its absence, but its lack of presence is something that makes the last triumphant paragraph of this otherwise marvellous book ring slightly hollow. That’s not Wright’s fault. It’s our history.

Comments powered by CComment