- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Lingering nostalgia

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lingering nostalgia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Azhar Abidi’s first novel, Passarola Rising (2006), told of some amazing adventures in a seventeenth-century flying ship, and it was a delight. His new novel could hardly be more different, yet gives just as much pleasure. It also tells a more probable story.

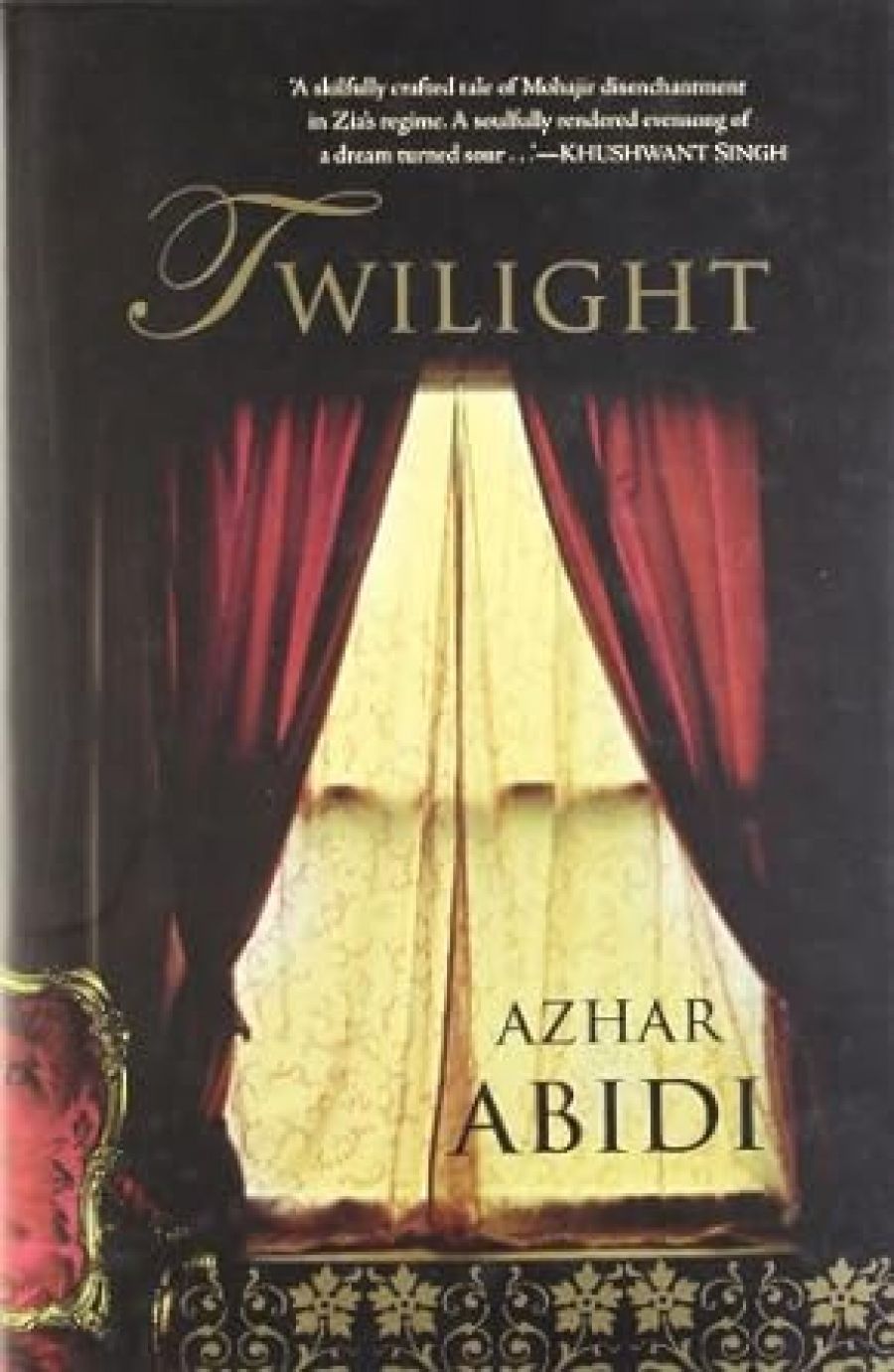

- Book 1 Title: Twilight

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $32.95 pb, 272 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The novel opens one evening in the spring of 1985, two days before the big reception to be given by Samad’s mother, Bilqis Ara Begum. Samad, Kate, Bilqis and the extended family are gathered around the dining table. The delicious spread is lit by an enormous chandelier whose dim wattage hardly reaches the adjacent drawing room, where the Empire furniture and faded Persian carpet disappear into the shadows. The ambience is one of past grandeur and a lingering nostalgia for lost glory.

Bilqis is a widow but remains in regular contact with her brother, her married sister and her niece. Since her husband died she has been lecturing part-time at the university, glad to have an interesting occupation and comfortable in the knowledge that, even though she lives alone, her sub-family of loyal servants will care for her on a basis of mutual commitment.

Away from the table, the family’s discussions of Samad’s foreign wife reveal their private perceptions of the mixed marriage, while flashbacks allow us to see how frequently Kate has probed Samad’s commitment to it. The marriage has provoked a gently problematic situation for Bilqis – not what she wanted, but not one she is going to oppose. Both the novel and the characters constantly sift through the adjustments that have to be made if generosity is to overcome suspicion. Abidi’s forte lies in his insights into the minds of individuals who must make a constant effort to prevent their ‘druthers’ hardening into demands or resentment.

At the reception, Samad is assailed on all sides by questions such as whether Kate has become a Muslim (she has) or if they will circumcise their sons (they will). But one of the guests is his former school friend Asim, who is rich and single. Jovial, backslapping and not very sensitive, Asim carelessly raises questions that Samad has been avoiding and is now forced to address. As the guests start making their goodbyes, he realises that although everyone has been polite and congratulatory, ‘he had broken a fundamental law’, an aesthetic law. He had succumbed to the Western concept of fair-skinned beauty, which, however fashionable, signified in Pakistan an inferior morality. Without labelling either position right or wrong, he suddenly becomes aware ‘how precarious this notion of love against all odds was ... And, in a moment of terrifying clarity, he understood that by his defiance against tradition he had let go of something essential.’

The revelation changes nothing of substance. He and Kate, who has also learnt a few things during the visit, return to Melbourne, have a daughter, buy a house. They do not return to Karachi for several years, during which the narrative focuses on Bilqis, struggling against age and change, and a sub-plot centred on Mumtaz, the servant-girl who willingly provides the extra care that Bilqis needs. But Mumtaz also develops a growing interest in the young man, Omar, who caretakes an empty house across the road, thus providing an unconscious but revealing foil to Samad’s unconstrained courtship of Kate, which involved sex before marriage. Mumtaz and Omar take weeks and months to get to know each other, achieving familiarity largely by phone when Bilqis is at the university; simply to be seen together involves serious risk. True love does finally have its way, but almost immediately Omar goes off to fight against the Indians in Kashmir, while Bilqis makes a long visit to Hampton, Melbourne, to see her granddaughter Tara.

Her return visit goes well because of the effort all three make to accommodate rather than criticise. Nevertheless, none of them is free from inner conflict; the moral strength and emotional climax of the book peaks in Abidi’s meticulous account of each individual’s attempt to match self-will against necessity. The goodwill aspect has made for a pleasing and interesting read, but the narrative becomes much tauter when Abidi deliberately challenges his characters, and indirectly the reader, to plumb each person’s resistance to another’s point of view. In Melbourne, Bilqis must swallow her resentment that somehow Kate has everything, including Samad and Tara, while she will return to a life inevitably dwindling to nothing; but when she says goodbye to them at the airport, she looks into Kate’s eyes and sees no animosity. Kate may have everything while conceding nothing, ‘but she was a mother now and did a mother not ultimately concede everything?’

After Bilqis’s return to Karachi, the external situation becomes increasingly politicised and disruptive, as Omar’s subsequent career exemplifies. But the disturbing events, even those of national significance, are assessed by their effect on the inner reactions of the characters. And since as readers we have been skilfully drawn into these people’s lives, we are equally obliged to confront issues that, although of a different time and another place, are nevertheless eternal and universal. The trick of making an audience think deeply while still giving them a good time is a precious one for a writer; here it is winningly abetted by the engaging, occasionally different English of the subcontinent.

Comments powered by CComment