- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Death of a government

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Death of a government

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Australian ritual of a federal election campaign every two or three years is one in which voters are invited to participate in hyperbole. Reality is magnified a thousand times as the actors perform a finely choreographed political quadrille while their every word and gesture are scrutinised for meaning and analysed for nuance. Yet for all the expensive and lavish hoopla that now constitutes an election campaign, Australians are a reluctant people when it comes to getting rid of governments, however short they fall in expectations. On only eleven occasions in the 107 years of federation have they opted for change.

- Book 1 Title: Howard’s Fourth Government

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian commonwealth administration 2004–2007

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $44.95pb, 303 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

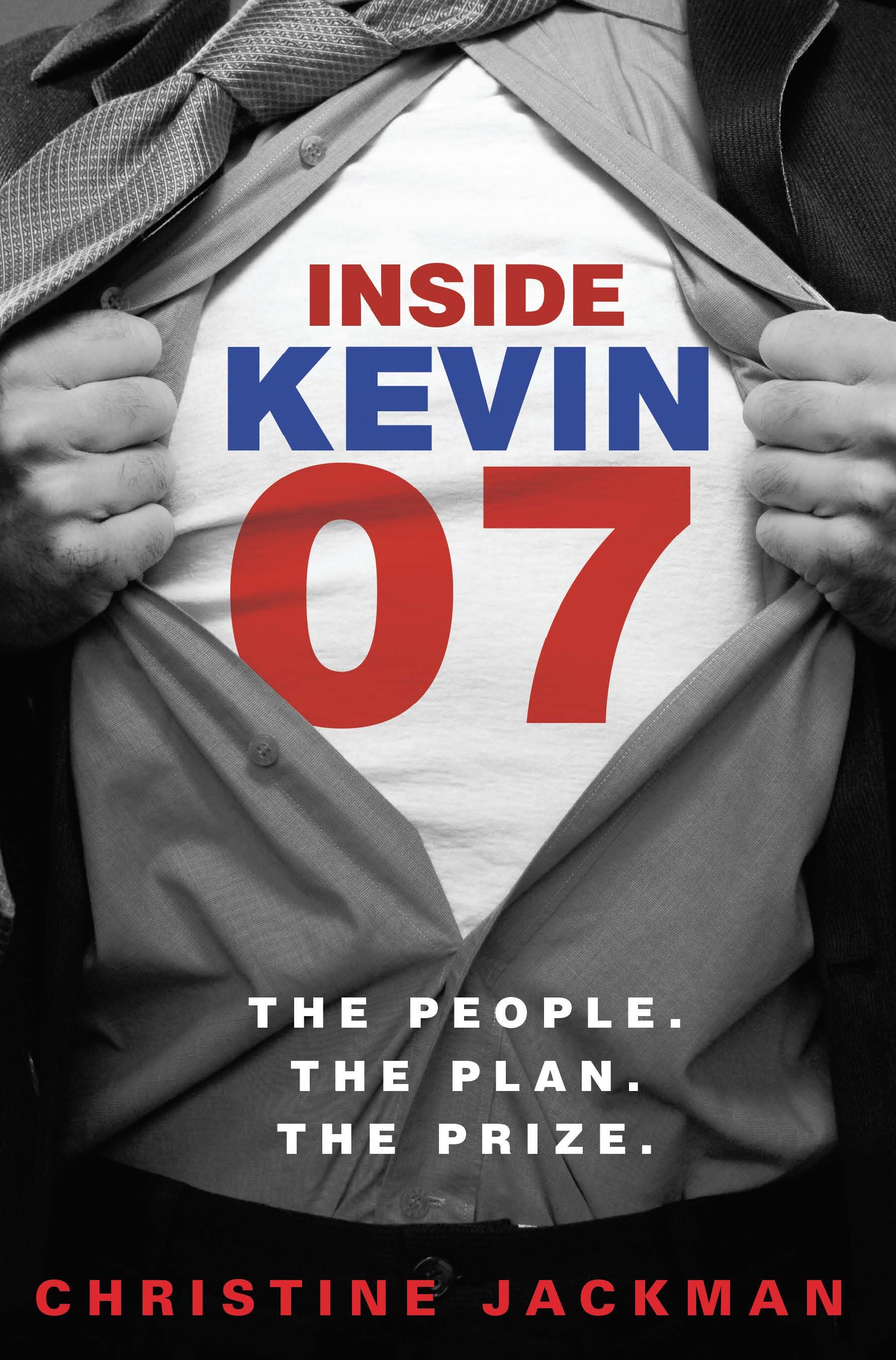

- Book 2 Title: Inside Kevin 07

- Book 2 Subtitle: The people. The plan. The prize.

- Book 2 Biblio: MUP, $34.95 pb, 320 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

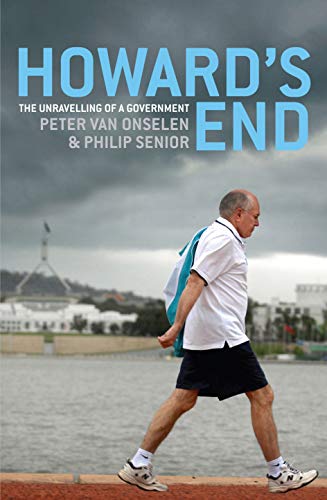

- Book 3 Title: Howard’s End

- Book 3 Subtitle: The unravelling of a government

- Book 3 Biblio: MUP, $34.95 pb, 272 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The comparative rarity of change brings an edge to the ritual; the stakes are indeed high. Yet we know remarkably little about why governments fade. Do they have a shelf-life beyond which they cannot muster the will to survive? Is there a life cycle that sees a government go from youthful zest to cautious middle age and on to feeble senility? What induces voter fatigue? Policy? Personnel? Leadership?

In many respects, the 2007 election campaign was an empty ritual: the electorate had made up its mind months before the polling date that it wanted a change, and it duly became the eleventh such change. The campaign itself revolved around twin axes that did not always intersect: a Labor Party seeking to defend its healthy lead in the polls, and a tired government going through the motions, not always convincingly, of trying to protect its incumbency. The campaign qua campaign changed little, if anything, in the mind of the electorate, which had already been exposed to a year-long quasi-campaign that never really looked like a real contest. And it wasn’t.

Election campaigns seem interminable while they are running, but once the race has been run and won, they quickly recede in the rear-view mirror. What was once fraught with significance now bears little relevance to anything; the torrent of words once pored over exegetically for subtle intelligence becomes once more just words. Once the side-show has packed up and left, the magic is lost like a summer fairground in winter. The caravan moves on.

Herein lies the difficulty in revisiting an election campaign, especially such a recent one. The danger in treating yesterday’s headlines as items of relevance for today is that the context for the urgency has gone; it is full of sound and fury signifying very little.

Peter van Onselen and Philip Senior, in Howard’s End: The Unravelling of a Government, sift through the ephemera of John Howard’s doomed campaign for a fifth term. But the subtitle is slightly misleading, as the government had clearly already begun to unravel long before the election campaign. What unravelled in those feverish weeks leading up to November 24 was the government’s own campaign for re-election, which merely reflected its state of disorganisation.

The problem of dealing with such recent events as a recent election campaign is that it is too close to memory and not yet old enough to qualify as history; it is a bit like yesterday’s fashions that have yet to acquire the aura of ‘retro’. Tony Abbott’s attempt to cast doubt on Kevin Rudd’s account of his early life is a case in point: in the context of a campaign it might have mattered to impugn Rudd’s credibility, but almost a year later it smacks of desperation and an attempt to divert attention from the main issues.

Christine Jackman’s Inside Kevin 07, a far more penetrating study, looks at the dynamics of Team Rudd and the gang that came up with the idea of ‘Kevin 07’, as slick and savvy a campaign theme as we have seen, cleverly melding elements of folksiness and contemporaneity. When Rudd himself first heard of it he had two questions: whose idea was it, and why wasn’t he told? Obviously, the man who demands to be fully briefed on everything was eventually convinced. Jackman is right when she suggests that it introduced something unusual into an otherwise dour election campaign – humour. No one plays politics as hard as Wayne Swan, and when he was asked by a reporter whether the Kevin 07 theme was just a personality cult, Swan shot back: ‘What do you want us to do – change his name? … I reckon Kevin’s a great name. It’s a bit like Wayne. It’s a daggy 1950s name and I think it’s got a lot going for it.’ And he was right. Out went Rudd the nerd and Rudd the politician; in came Rudd the bloke. It was the bloke who won the election.

The Howard years (1996–2007) had been bleak for the Labor Party. For the first time it was being repeatedly thumped by the conservatives while nominally united. The previous long expanses of non-Labor rule – the 1920s, the 1930s and the protracted Menzies era – all occurred while the ALP was divided and weak, having on each occasion suffered significant defections. Yet no such division could explain Labor’s failure to unseat Howard.

Perhaps the answer lies in what Labor failed to do earlier: apologise for the arrogance of the Keating years and the bitter divisions sown by his prime ministership (1991–96). Without that repudiation, even the avuncular Kim Beazley remained ‘handcuffed to history’. Keating’s posturing and haughtiness made the apparent ordinariness of Howard more appealing than it should have, and helped obscure the latter’s extremist tendencies. Another element in Labor’s failure was the paucity of leadership, akin perhaps to the 1920s, when party worthies such as Frank Tudor and Matthew Charlton were made to look like the plodders they were against the wiliness of Billy Hughes and the polish of Stanley Melbourne Bruce.

Labor’s turnaround from easybeat to victor is a remarkable story. Just as Robert Menzies did not ‘make’ the Liberal Party on his own, Kevin Rudd was not solely responsible for Labor’s resurgence. But in each case they were central to the cause.

The Howard years saw Labor, for a professional political outfit, uncharacteristically unreflective. Jackman quotes the astute Swan (now the federal treasurer) as identifying Labor’s crucial weakness in not having made the transition when it lost government in 1996 and compounding it by refusing to have the necessary debate about what that defeat meant.

The Keating years did not just seed divisions between the government and the people; they also exposed dangerous fault lines within the Labor Party itself, a ‘poisonous chasm’, as Jackman puts it, between the leader’s office and party headquarters. The contagion of division spread to caucus, plunging the ALP into what the energetic Mark Arbib, now a senator, called its lowest point ever. It took a generational change for the damage to be repaired, but not before further significant damage was inflicted on the party by its own in the now infamous The Latham Diaries (2006).

The hitherto private musings of the former Labor leader were probably an accurate reflection of the state of a party that had become dysfunctional in the extreme. Jackman captures their flavour nicely when she writes of how they erupted ‘like a pent-up sewer that rained poison and bile over almost everyone involved in federal Labor’. But this was the past, and it was left to younger operatives such as Arbib and the quietly determined Tim Gartrell to recalibrate the party towards the future.

But all the organisational skill in the world will not a silk purse from a sow’s ear make. It took the accession of Rudd to the party leadership in late 2006 for the door to be finally closed on the unhelpful past. Rudd’s energy and the organisation’s strategic skills were a good fit. Rudd, the asset, was marketed to perfection.

Two things stand out as salient points in the political landscape in these accounts of Howard’s demise and the rise of Rudd. One is the changing way in which politicians are connecting with a wary and often sceptical electorate. Both the van Onselen–Senior and Jackman books single out Rudd’s appearances on the morning television talk show Sunrise as vital in his connection with the electorate, and in his crucial transformation from political wannabe to ‘Kevin from Brisbane’. The extraordinary thing is that Sunrise goes out of its way to be not just apolitical, but overtly anti-political with one of its co-hosts loudly interrupting with a ‘No, no, no’ if a politician makes a political statement. It has read its audience well (interestingly, Sunrise stopped advertising appearances from the prime minister because viewers turned off). Politicians gained credibility on the show by not behaving like politicians.

The most fascinating quote (among many fascinating ones) in the Jackman book comes from Rudd’s former boss Wayne Goss, who remarks that Rudd has worked hard at becoming normal, but he doesn’t think he will ever quite get there. But, he adds, do Australians really want a prime minister who is normal? A close second is an amazing burst of vitriol from Keating at Gartrell (‘You’re no good’) and Keating’s wild self-delusion of a political comeback to take on Howard.

The second standout feature is how the political parties are portrayed, and how they figure (or do not figure) in an election campaign. Here are two contending élites jostling for preferment; their foot soldiers are no longer party members but marketing men and women, strategists and pollsters, spin doctors and advertising whizz kids. Party members on both sides are relegated to non-speaking roles as mere passive spectators. The mass party, it seems, is no more in an age of the largely taxpayer-funded cartel.

[DROPCAP] Covering a much broader canvas than a month-long election campaign is Chris Aulich and Roger Wettenhall’s weighty consideration of John Howard’s fourth and final term in office, which appears in the latest volume of the University of Canberra’s admirable ‘Australian Commonwealth Administration’ series. In its dense and closely argued study of the government’s administration, there is a gleam of insight into what is referred to above as how long-term governments die. An eclectic range of academic authors, examining the gamut of government activity, concludes that, in both an administrative and political sense, the fourth term was not Howard’s best.

Short-term political fix was the order of the day as it became increasingly clear that the government’s support was waning. In an effort to convey the illusion of policy freshness, the government strayed far into the administrative no man’s land which separated current policies from their knowledge bases. Examples of this abound, most notably in the fiasco over the Mersey Hospital in Tasmania, without strategic linkage with the Tasmanian government and its expert advisory group; the intervention in the Northern Territory Indigenous communities, without any attempt to complement existing policies in the Territory; and the so-called water initiative, which, on announcement, had yet to include any substantial discussion with the Murray–Darling Basin Commission and its body of experts.

In terms of its management of the public service, the Howard government has left a questionable legacy. As John Halligan notes, the initial years were marked by a government estranged from the bureaucracy, but as they grew closer it sought to reshape the service with its ‘new public management’ approach, supposedly more in line with its neo-liberal agendas. Core programmes such as outsourcing were seen as having failed, and in its final term efforts were made at fine tuning, but the corporate model exposed serious flaws in portfolio management (the Rau and Alvarez affairs at Immigration being notable examples), as well as grave deficiencies in governing by the political executive (such as the AWB scandal).

In a chapter on federalism under Howard, Andrew Parkin and Geoff Anderson draw an unusual but apt comparison with the Whitlam government, noting that a recurring feature of the Australian system is that challenges from the centre tend to produce counterbalancing thrusts from elsewhere. Howard, like Whitlam, stimulated a resistance and subsequent policy renaissance among the states that Parkin and Anderson suggest will, as was the case post-Whitlam, leave the states more vibrant than before.

Mary Walsh and Heba Batainah put Howard’s aversion to multiculturalism under the microscope and trace its replacement by ‘citizenship’ as a key change in the government’s fourth term. Here, they perceive a repositioning of Australia with a more insular focus on our global world, which they label ‘Australia first’. While its impact has yet to be determined, they raise the real concern that the mechanisms put in place to strengthen social cohesion might well produce social divisiveness.

By far the most provocative chapter in the book is contributed by John Uhr, from the Australian National University. Looking at issues of public integrity, Uhr raises not only serious concerns about governance but also a structural weakness in the methodology of Australian political science and its slight focus on theory. He sees the debate over public integrity, of which there has been much, as lacking an appreciation of the strengths and weaknesses of governance structures, as well as paying scant attention to the government’s own defence of its performance in the public integrity context.

Uhr focuses on the role of Tony Abbott as public advocate for the Howard government’s integrity, and finds that Abbott’s defence comes down to a justification of prudence over moralism, of practical political reasoning over abstract theory, and of ‘the ultimate judgment of voters over the sermonising judgment of virtuous commentators’. While he is unconvinced by Abbott’s case, Uhr argues that Australian political analysis is weak and misdirected when dealing with issues of public integrity, and he urges a reconstruction of the three core concepts of truth, honesty and accountability by reconnecting them to the discipline of political theory which barely features in Australian political commentary:

I contend that there is something unrealistic about expecting truth in politics. Politics is adversarial, not consensual; political success is manipulated, not peer-reviewed; the determination of party political leadership and the determination of who gets the power to govern are not evidence-based processes.

Gone the Howard government may be, but in its wake we have much to ponder. The unfolding character of the Rudd government will inevitably be judged as to how like or unlike it is when compared with its predecessor.

Comments powered by CComment