- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Danish Lite

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Danish Lite

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The greatest play by the greatest playwright, Hamlet has over the centuries daunted readers far older than Holden Caulfield. Today, however, he would have another choice: he could read the novel of the play, and one written especially for his age group. John Marsden, the Pied Piper of Australian YA literature, has decided to lead his vast army of devotees into Shakespeare country – to be specific, Elsinore. And why not? The progress from adolescence to maturity is the very stuff of YA fiction, and Hamlet is a story about growing up. Most stage Hamlets are too old. Holden describes the Danish prince as a ‘sad, screwed-up type guy’, and one of the defining features of Marsden’s often dark fiction is exactly this kind of young protagonist.

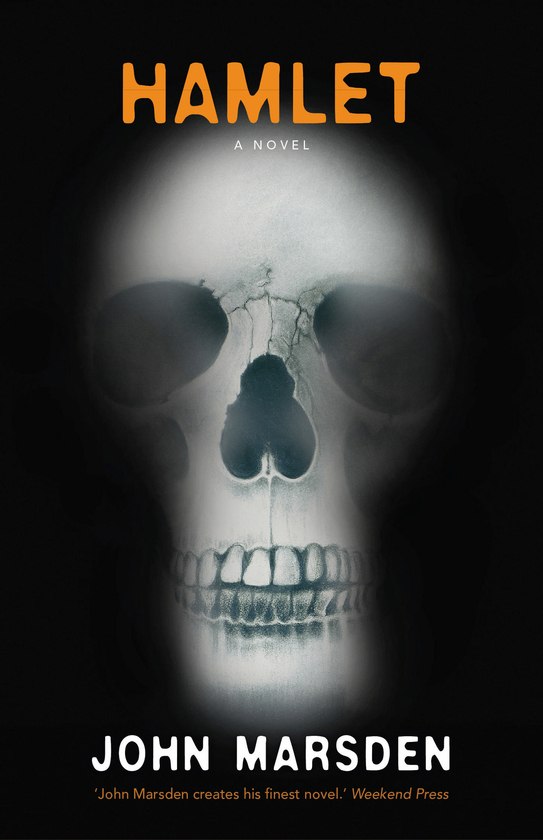

- Book 1 Title: Hamlet

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $29.95 hb, 228 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In the first brief chapter, Horatio and Hamlet, who is home from boarding school, are in the prince’s bedroom at Elsinore. Horatio is quizzing his friend on whether he believes in ghosts. Hamlet, refusing to be drawn, brushes him off: ‘My bum’s getting sore. Let’s play football.’ As an opening, this hardly matches the theatrical drama of the ghost of a dead king appearing on castle ramparts, but reluctant male readers in particular will be reassured that they are on familiar ground and that this prince in black jeans is just like them, an adolescent grappling with the problems of parents, first love and raging hormones.

Popular with everyone because of his beauty and charm, Hamlet has ‘always been strange’, as his friend Horatio observes, and a bit of a ditherer. He has trouble humanely dispatching a wounded badger; watching his hesitation and the resulting bloodshed, Horatio thinks, ‘He went to water … I could have done it with one clean stroke.’ Hamlet is the classic under-achieving son of a powerful man, and some of his strongest memories are of his failure to live up to his father’s exacting standards and of the weakness he always exhibited in his presence. He seems ambivalent about his father’s recent death, admitting to Horatio that he never visits his grave. Shakespeare’s prince is hot for revenge the minute the ghost mentions the word murder, but Marsden’s Hamlet is slower to stir. All his life he has desperately sought his father’s approval, and it is this that propels him towards his tragic end.

The novel takes few liberties with Shakespeare’s plot. Most of the big scenes and famous soliloquies are included, but language must have posed an early problem: go with plain English for maximum comprehension, or try to convey the richness, complexity and resonance of the original verse, the famous words and metaphors that make the play, as the old lady complained, ‘full of quotations’? Marsden opts for a bit of both. In dialogue, he lifts phrases here and there and paraphrases in other parts, but in words that are not unsympathetic to the original text and that often attain a poetry of their own. In a rewrite of the play’s most famous soliloquy, Hamlet muses to Ophelia on whether it is better ‘to live or not to live … to breathe the painful air, or to sleep … to stand in the shallows with a sword to fight the surf, or to let the waves wash you away’. This is a more than commendable version of taking arms against a sea of troubles, and when Hamlet goes on to criticise his own passivity his speech is in tune with the original text. But it’s a long way from ‘my bum’s getting sore’.

Marsden can also give Shakespeare a run for his money when it comes to word play and sexual innuendo. He gives an extended spin to the ‘country matters’ scene in which Hamlet teases Ophelia about lying between her legs as they sit and watch the players; at other times, the spin is pure Marsden. Is Horatio’s love for Hamlet strictly platonic? Bernardo, a young officer, notes a ‘queer tension’ when he witnesses the two together on Hamlet’s bed. At a banquet, Horatio is puzzled by the queen’s constant fingering of a pepper-pot as she sits gazing up at her new husband (‘She had always been so punctilious when it came to table etiquette’), while Ophelia spends hot afternoons shut up in her bedroom, masturbating. Polonius raps on her door: ‘Open this door. I know what you’re doing.’ ‘I’m coming. I’m coming now,’ Ophelia gasps. That same door also frustrates Hamlet: even with ‘his hand upon the knob’, he ‘cannot push against the reluctant door to open it’ and he slinks away, ‘disgusted at his lack of resolve’. He works off his sexual frustration in the kitchen gardens late at night: ‘hens strangled and sows stabbed, vines ripped down and soft fruit plucked and trampled.’ What fun they’ll have in the classroom deconstructing this Hamlet.

They might also enjoy the satire. When Claudius is debating where to banish this Danish prince, he briefly considers Australia but, ‘No, he’ll end up marrying some unsuitable girl’; the new king promises to ‘lower interest rates, increase employment, build better roads and hospitals, and reduce taxes’; and after the murder of Polonius he tells Gertrude, ‘We’ll set up an enquiry, so it looks as though we’re doing something.’

Reading this handsome hardback, with its arresting cover image, is unlikely to result in the sort of appreciation that comes after prolonged engagement with a Shakespearean text, but it may be a way for some students to approach the play and to get a handle on the plot and characters. After that, as Holden says, you just have to read the play. I sense a series in the making.

Comments powered by CComment