- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Being Manning

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Being Manning

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In death, as in life, Manning Clark casts a long shadow. The author of A History of Australia (1962–87) remains a figure of considerable interest and contention in intellectual and cultural debate. Clark’s imposing oeuvre has its detractors and admirers. In pioneering a fresh and richly imagined awareness of national history for a post-World War II generation of Australians, Clark was an inspiring teacher. He encouraged his students to work with primary source materials. In doing so he assembled for publication three volumes of Australian historical documents that brought the underpinnings of Australian history into the ken of general readers. The publication of these documents served as something of a dress rehearsal for the great task Clark set himself: to write a version of the Australian story he conceived in grandeur and tragedy, nobility and ordinariness. As Carl Bridge has noted, Clark’s History has been seen by some as ‘a majestic blue gum of Australian historical scholarship’, and by others as ‘gooey subjective pap’. With the appearance of each volume, reviewers were sharply divided about the merits of Clark’s style, his interpretation, and even the veracity of his history. But while doubts remain, distance has conceded to the History its standing as a work of literature of the imagination that might sit in the same company as the paintings of Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan, or the novels of Patrick White.

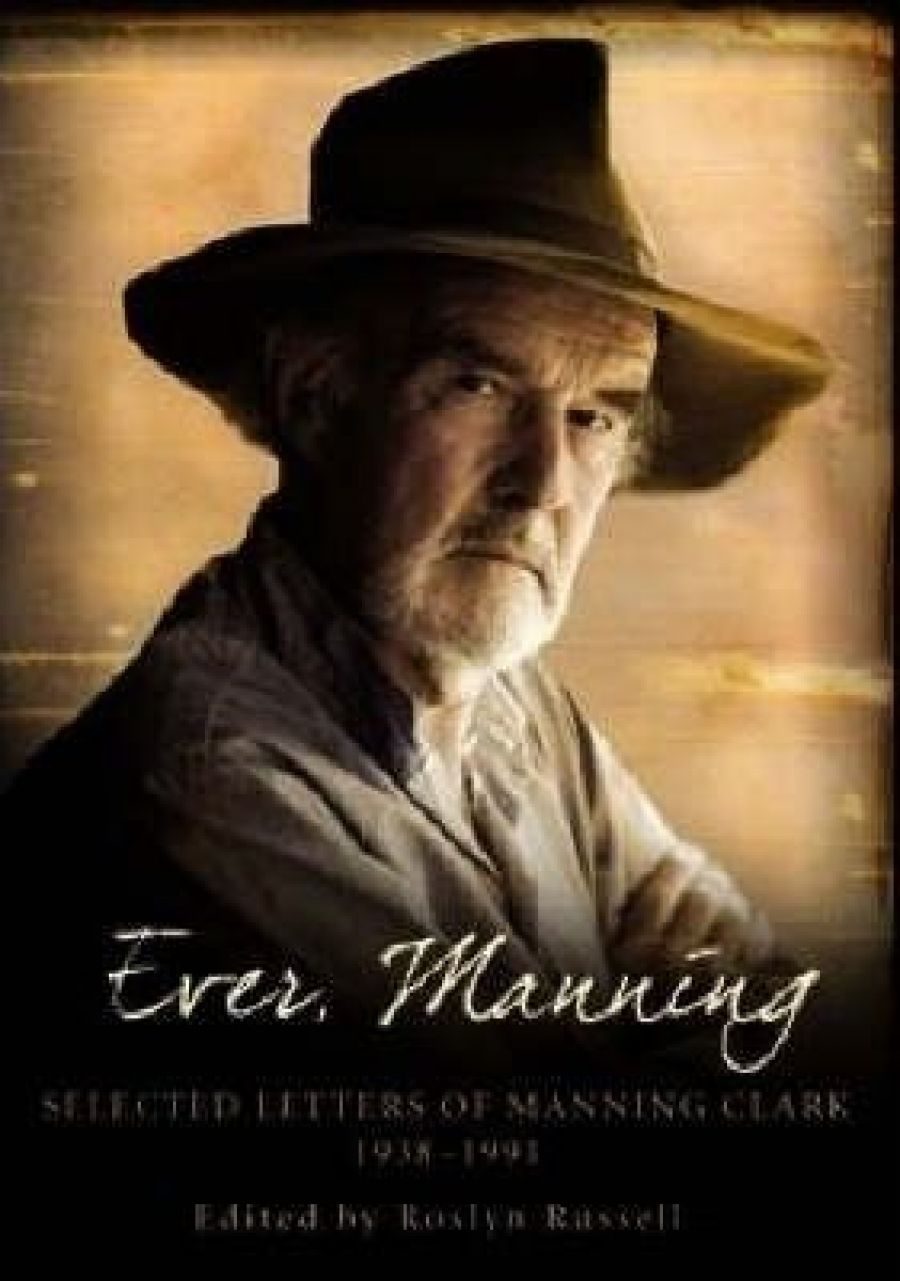

- Book 1 Title: Ever, Manning

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected letters of Manning Clark 1938–1991

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $65 hb, 552 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Notwithstanding the immense workload of the History and the struggle Clarke faced to realise his vision, other work flowed from his pen. These included an account of a journey to the Soviet Union (Meeting Soviet Man, 1960), the immensely successful A Short History of Australia (1963, 1986), two collections of short stories and a study of Henry Lawson (1978, 1985). Two volumes of autobiography followed: The Puzzles of Childhood (1989) and The Quest for Grace (1990). Emerging in his later life as a kind of seer or national prophet, many of Clark’s speeches, broadcasts and lectures were brought into print. Various post-humous publications have followed: works by Clark himself; critical assessments of his work examined in the broader context of Australian historiography; and a volume of his correspondence with the Melbourne historian and memoirist Kathleen Fitzpatrick. Controversy – a stalking companion to Clark in life – has raged intermittently but with extraordinary vigour and bite. The historian’s reputation was assailed by his former publisher Peter Ryan. On dubious evidence, a campaign by the Courier-Mail in Brisbane asserted that Clark had been an agent of influence in Australia for the Soviet Union, and that he had been awarded the Order of Lenin for his services. Most recently there has been a debate about the false claims Clark had made that he was present as a witness to the Nazi persecution of the Jews on 10 November 1938 (see Brian Matthews’s ‘What Dymphna Knew: Manning Clark and Kristallnacht’, ABR, May 2007).

Rich in contradictions and enigmas, Clark presents himself as a prime subject for biography. Two are close to publication: the first, by Brian Matthews, will appear later this year, and Mark McKenna’s will follow in 2009. In the meantime, we have this gathering of Clark’s own letters, selected and edited by the Canberra historian Roslyn Russell, who served as the last in the line of Clark’s numerous and loyal research assistants, and who also worked closely with his widow, Dymphna Clark.

As Clark’s selections of documents once stood as preliminaries to his A History of Australia, so these letters serve as a curtain-raiser to the biographies yet to come. While it is true that the best of the letters are valuable and immensely interesting in their own right, they pose many questions that are not always illuminated in Russell’s affectionate and sympathetic introduction, or in the short essays that open each of the thematically arranged selections of Clark’s letters from 1938 until his death in 1991. As editor, Russell declares her allegiance to Manning and Dymphna. She recalls her almost daily visits to the Clark family house in Canberra. She tells us that she conceived her work on Clark’s letters as her way of keeping fresh the memories of Manning and Dymphna, of paying a debt of gratitude to them for ‘taking me into their hearts and home’. While Russell’s motivation is gallant, such declarations signal a warning that Clark’s account of himself, raw and vulnerable as it is, has been spared close editorial scrutiny. Perhaps Russell believes that Clark’s revelation requires no mediation, that it is for readers to respond and to draw their own conclusions as they choose. She sees Clark as he saw himself: the historian as hero persisting against the odds and the doubters to realise a great vision; and as a man searching for a faith to live by and a reassurance that life held meaning and purpose. Clark’s flaws, in particular his intense self-absorption and his extraordinary denial of the legitimacy of criticism, are not confronted in her commentary.

Russell’s selection of Clark’s letters begins when he was studying at Balliol College in Oxford, for long the college of choice for the best and brightest of the Melbourne History School presided over by R.M. Crawford. The letters are arranged in a biographical sequence that illuminate the major landmarks of Clark’s career: his time abroad at the end of the 1930s; his great teaching years in Melbourne and Canberra; the gargantuan task of conceiving and writing the History; his ‘fate’ at the hands of his critics; his larger interests in politics and in world affairs; his emergence as a national prophet and commentator; and, as death approached, the sense of a shrinking world.

Running throughout the letters is the rich and emotionally charged story of Clark’s often troubled relationship with his wife Dymphna (never adequately explained or contextualised by Russell, whose tact prevails at all times) and his compensating search for emotional fulfilment and sympathetic understanding from other women. While Dymphna was the rock in Clark’s life, it is also true that she saw him with all his flaws and was hurt by him to the point where, more than once, she contemplated ending the marriage. Balanced against this is the moving story of Clark’s family life, and of his hopes and ambitions for his children. Especially marked is his affection for his first-born son, Sebastian, and later for Axel Clark, who achieved success as a literary biographer before dying from cancer. If Clark’s letters to the young Axel worry about the boy’s lack of application in his studies, they also have a lightness of touch and a mischievous humor that is not otherwise much apparent in the prevailing seriousness of Clark’s letter-writing.

It is sometimes difficult to draw firm conclusions from selected letters of well-known personalities. How representative are the selections? How were they made? What has been left out and why? As Russell explains, she was not able to draw on any complete and organised collection of his letters. Hers was a gathering exercise, trawling through library and archival holdings, but also relying on letters still in private hands, many of them, despite the large holding of Clark’s papers in the National Library of Australia, remaining with the Clark family. Russell has made some good discoveries (not the least of them Clark’s painfully candid letters to the historian Lyndall Ryan), but, inevitably, many letters by Clark have not yet come to light and others are restricted. We may guess that the publication of this pioneering volume, and the two biographies, will yield new troves, but it may be too much to expect anytime soon a more dispassionate volume where Clark’s full range of letters is drawn on to create the definitive ‘self-portrait’ that is only half-painted here.

But while the impediments are understood, some omissions are stark. Notable is the absence of any letter written to Clark’s father. While long letters were written to the mother and also to Clark’s sister Hope, the father is virtually absent. Certainly no letters addressed to him are present (were any written or did any survive?), though there is an occasional cursory wave of the hand. Rather, it is to his mother that Clark writes, with much affection, and it is her he tells of life at Oxford, the progress of his studies and his hopes for his marriage to the young Dymphna Lodewyckz. It is from his mother that Clark in 1938–40 hungrily seeks news from home: ‘Tell me everything about my beloved Australia. Just tell me about her “sights and sounds”.’ In his first volume of autobiography, Clark gives an account of his relationship with each of his parents (not easy on either count). This doesn’t seem to have been drawn on to contextualise the puzzling absence of letters to his father. It would have been interesting to compare the differences (if any) in Clark’s own considered ways of ‘speaking’ with his parents, but, again, we must wait to see what the two biographers offer on this front.

Make no mistake, though, this is a rich and absorbing volume of letters, as interesting for the life of a deeply complex man as for the story it tells of his great endeavour, the writing of A History of Australia. Once, driven to distraction by Clark’s intensity, R.M. Crawford exclaimed that there was ‘a lot to be said for plain blokes who have never read a line of Dostoevsky’. In its instance, there was a justification for that explosion of professorial irritation uttered now more than half a century ago, but here it has no place. Without Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, without Bach and Mozart, without the Brontë sisters and Dickens, without the King James Bible, and of course without Lawson, these letters would lack depth and colour, and their mighty sense of life gusting through the sails. As the letters (together with Russell’s detailed notes) attest, Clark’s learning was immense and his sympathies wide. His aspiration to be a better man than he was or could be remained strong until the end. There are some wilful cruelties and dismissals, and there is much pain and angst. But there is idealism too, a nobility of the spirit and a keen awareness of the potential in men and women to live good and fruitful lives. These letters reveal much about an extraordinary and complex Australian, and they explain why it was that Clark found himself (as he confided in a letter to Dymphna in 1938) ‘always picked on for a heart to heart chat on the eternal questions’.

Comments powered by CComment