- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: A contrary life

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A contrary life

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

During the hot summer of 2002, I visited Canberra for the first time and alternated between the air-conditioned confines of the National Gallery and the National Library of Australia. It was in the latter that I stumbled upon The Flower Hunter, an exhibition of works by the Australian flower painter Ellis Rowan, whose life is now chronicled in a biography by Christine and Michael Morton-Evans.

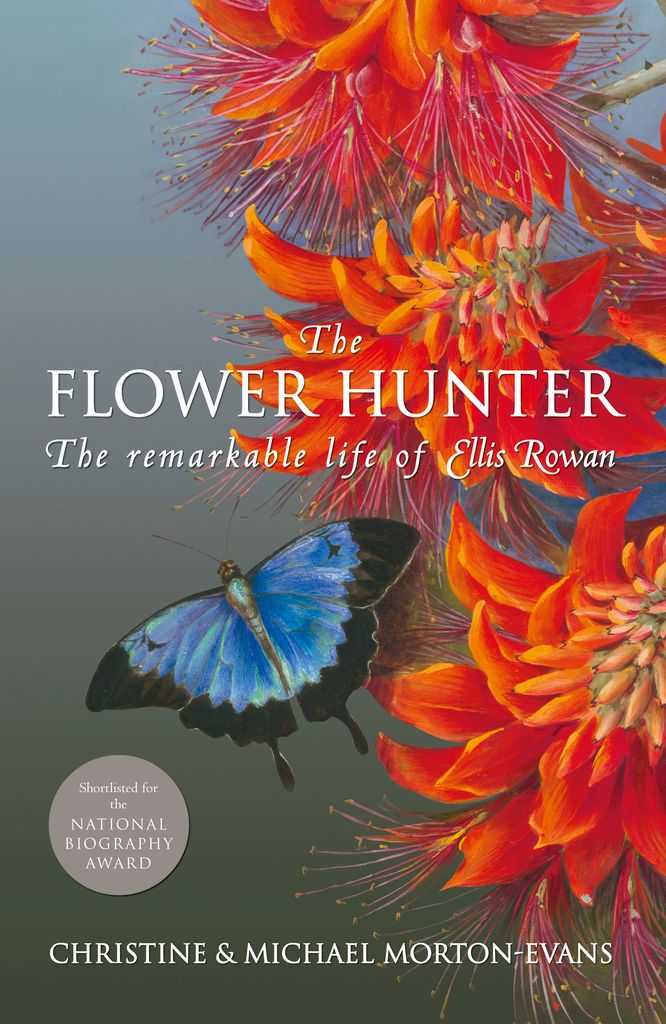

- Book 1 Title: The Flower Hunter

- Book 1 Subtitle: The remarkable life of Ellis Rowan

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $34.95 pb, 328 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

When I was growing up I was vaguely familiar with Rowan’s work, having lived with my grandmother, whose dining-room walls were decorated with a series of inferior imitations of Rowan’s delicate floral paintings. By then, however, both her fascinating life and her beautiful paintings had slipped into relative obscurity, making it seem unbelievable that, during her lifetime, Rowan’s popularity and renown were such that ‘when her death was announced in 1922, there was hardly a household in Australia that did not know her name’. Until one reads about Rowan’s life, such a claim seems excessive. She was indeed remarkably well known for both her paintings and the more colourful and salacious details of her personal life, which included a facelift at a time when the procedure was still highly experimental.

At the heart of this vibrant biography is a curious and successful combination of elements of art history, social history and detailed, at times almost novelistic, storytelling. Particularly compelling are the many portraits of Rowan as a traveller, ‘in her Victorian attire, corset under a high-necked blouse, ankle length skirt and high buttoned boots, navigating her way through murky swamps and snake-infested jungles, all in search of something new and unknown to paint’. Born in Melbourne in 1848, Rowan was a maverick and an eccentric, famous for her self-confidence, ambition and artistic talent. For much of her life she was a relentless self-promoter, proudly flouting convention, dyeing her hair bright henna red and leading a peripatetic existence that seems remarkable, even today.

It was Germaine Greer, writing in The Obstacle Race (1979), her study of women painters and their work, who noted that ‘flowers were chosen as a fit subject for people who were not meant to take their artistic activity too seriously’. As the authors of The Flower Hunter point out, Rowan’s was an age in which women’s roles were largely confined to matters of ‘home and hearth’, but Rowan, who routinely outsold male contemporaries that included Charles Conder, Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, took her painting seriously.

She appears to have prioritised her art over domestic obligations and expected those around her to do likewise. Another of this biography’s strengths is the even-handedness with which it explores her attitudes to such matters without condescension. Such was her dedication to her art that she traipsed through the swamps and jungles of New Guinea in search of all seventy-two known species of the Bird of Paradise. She was seventy years old at the time, and she found and painted all of them.

Much of this biography documents Rowan’s extensive travels across Australia, New Guinea, the United Kingdom and the United States. Somewhat ironically, it was her 1873 marriage (to Frederic Rowan, a former British Army officer) that enabled her both to paint and travel widely. Rowan frequently accompanied her husband on business trips, venturing out into unfamiliar terrain to paint indigenous flora. She returned only briefly to Australia, where she gave birth to a son in 1875.

Alongside its exploration of Rowan’s personal life and travels, the other achievement of The Flower Hunter is its exhaustive chronicling of Rowan’s campaign for her works to become a national collection in their own right or, at the very least, part of a state or national gallery’s permanent collection. Although Queen Victoria herself owned three of Rowan’s works, curators and politicians in Australia argued about the value of her paintings, debating their artistic merits and whether or not they were ‘proper art’ or simply particularly competent botanical specimen paintings. The Queensland Museum eventually acquired 125 of Rowan’s paintings (which went on display for a short time in 1990) and a further 970 works are carefully preserved between layers of tissue paper in drawers at the National Library, where they may be viewed on request, but otherwise remain largely hidden from the public gaze.

It is unfortunate that Rowan’s place in the annals of Australian art history is largely tenuous and her reputation insecure. It is to be hoped that this well-researched and eminently readable biography inspires new interest in her art, not just in her intriguingly contrary and singular life.

Comments powered by CComment