- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Twofold hero

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Twofold hero

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the days of the Great Anzac Revival, it is unusual to find an Australian VC who has not been the subject of a biography. Here we have one of the most famous of them all – Arthur Blackburn (1892–1960). I was surprised to find that this is the first biography of him.

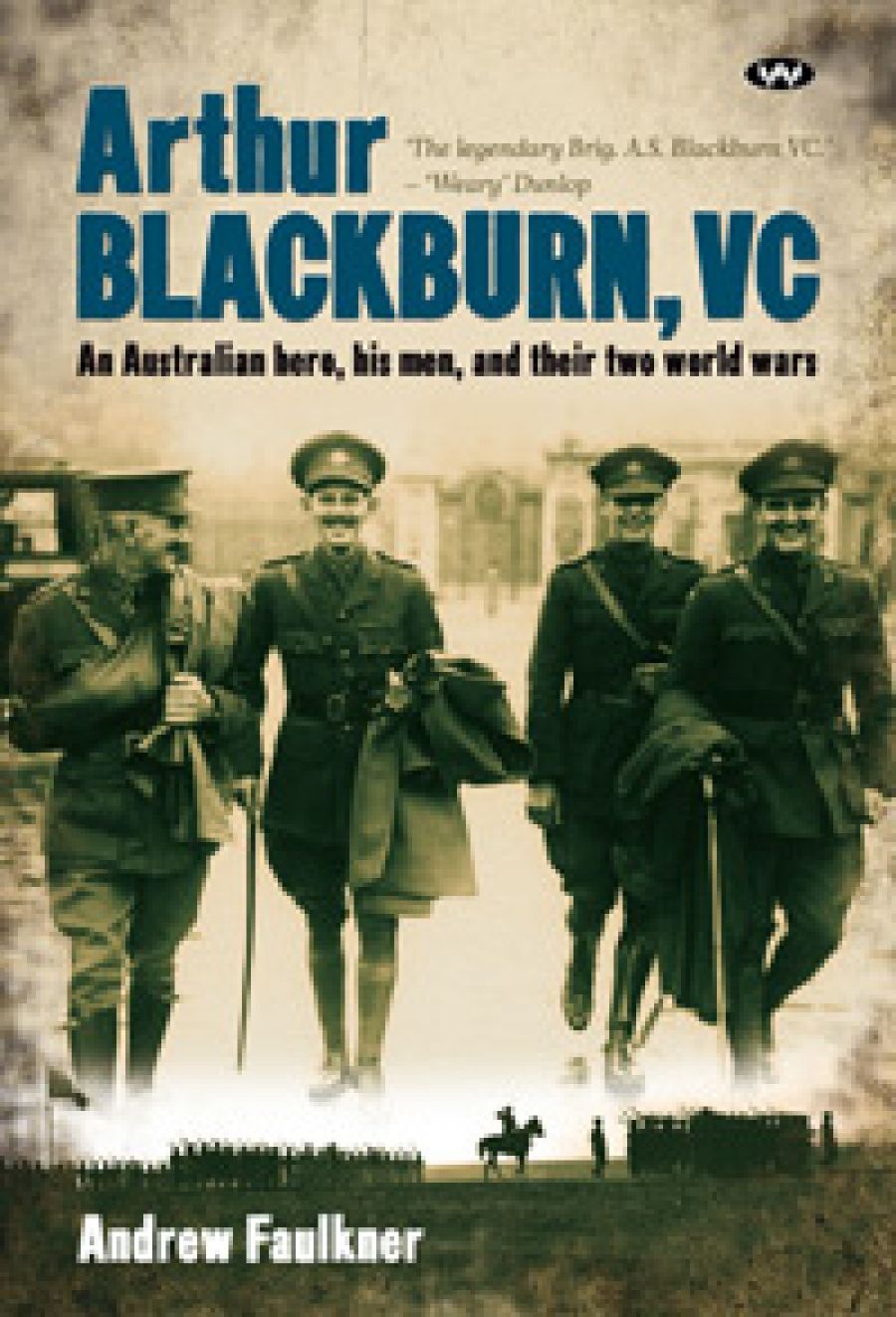

- Book 1 Title: Arthur Blackburn, VC

- Book 1 Subtitle: An Australian hero, his men and their two world wars

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $45 pb, 498 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Blackburn, like so many Australians of his generation, joined the conflicts of 1914–18 and 1939–45 without hesitation. These men considered that Britain’s cause was Australia’s cause. They were neither gulled nor tricked by propaganda into joining up. It is hindsight of the worst kind to see these men as passive victims of a cunning imperial plot.

Faulkner wastes no time dwelling on Blackburn’s early years. Blackburn became an Adelaide solicitor and, when war came in 1914, was one of the first to enlist. He was also one of the first to land at Gallipoli and, with a companion, has a claim to have penetrated further inland than any other Australian soldier. The problem was that there was no one with them. The tortuous country and the rapid Turkish response put paid to any general advance. In truth, the operation never had the slightest chance of success. Blackburn’s part in all this is well told, but Faulkner’s conclusion that ‘the British Empire was not quite as good as it thought it was’ would have jarred with his subject.

Blackburn then moved to France and had the misfortune to participate in the Battle of the Somme, in 1916. Worse still, he participated in one of the most futile episodes within the battle: the bloody and inconclusive advance from Pozières to Mouquet Farm. It was here that he won his VC for driving German machine-gunners from their positions and for capturing a considerable portion of enemy trench. This incident is written with understatement by the author, a welcome change from those who mistake winning the VC with winning a war.

After the Somme, Blackburn returned to Australia for recuperation, but his health did not permit him to return to the war. In civilian life he proved that he could be a class warrior as well as a military one. He became a National MP in the South Australian parliament and proved as adept in breaking strikes at the Port as he had been in dealing with enemies abroad.

After a long and distinguished term as Coroner, Blackburn was quick to enlist in 1939. His record in World War II was as extraordinary as that in the first. His main action happened to be against the Vichy French in Syria, where, at the head of a machine-gun unit attached to the Free French, he was on hand to accept the surrender of Damascus. He was later dispatched to a lost campaign in Java, where he was captured and endured with fortitude and good spirits three years of hell in various Japanese POW camps. On his return to Australia, his frame, scrawny at the best of times, looks positively skeletal in one of the many excellent photographs that accompany the book. Faulkner describes these events with the same restraint that characterises his writing about the earlier war. Neither the Germans, nor the Vichyites, nor the Japanese are demonised, though Faulkner does not hesitate to detail the inhumanity of some of the latter in their dealings with Allied POWs. In the postwar period, despite poor health, Blackburn worked hard for the rights of returned soldiers and spent his retirement near Mt Lofty.

Blackburn’s is an interesting tale and is well told. The emphasis is strongly weighted to the military side of Blackburn’s career, but, in this case, that is right and proper, as the world wars overshadowed his whole life. Despite occasional outbursts against Germans and communists, Blackburn is portrayed as a tolerant man, not inappropriate for one who had endured considerable sufferings. He was a man of his time but, as the author demonstrates, one who was able to make the most of it without losing his equanimity or good humour. For that, as for his military exploits, he deserves the title of Australian hero.

Comments powered by CComment