- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Custom Article Title: Libby Robin reviews 'Cane Toad Wars' by Rick Shine

- Custom Highlight Text:

Cane Toads are peculiarly Australian. They don’t belong, yet they thrive here. They breed unnaturally fast – even faster than rabbits. They are ugly, ecosystem-changing, and despised. Introduced in 1935 to eat the pests of sugar cane in Queensland, their numbers have exploded right across Australia’s ...

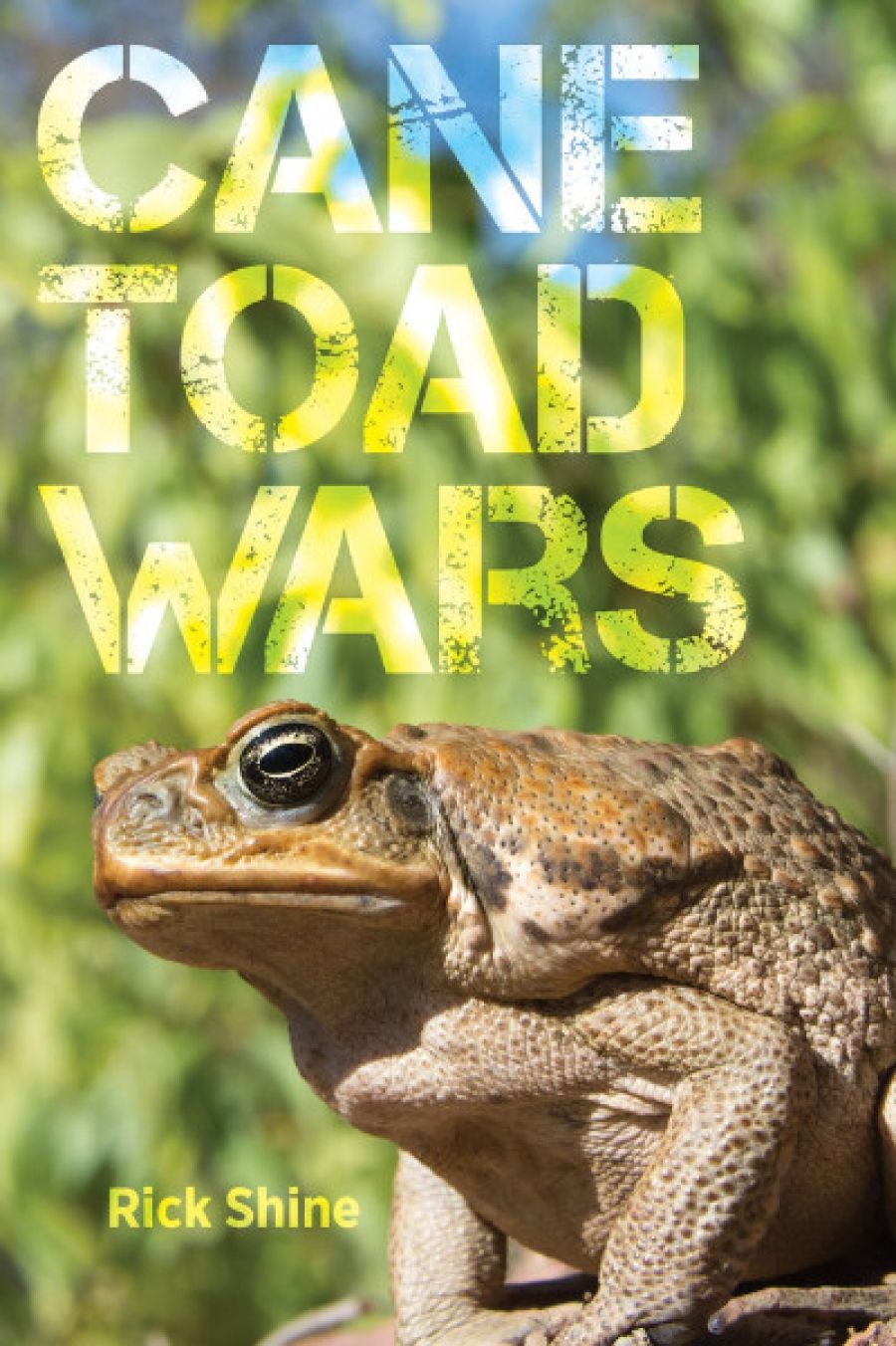

- Book 1 Title: Cane Toad Wars

- Book 1 Biblio: University of California Press (Footprint), $49.99 hb, 288 pp, 9780520295100

As Rick Shine explains, an invasive species exposes ‘an entire fauna and flora’ to a devastating newcomer. Native animals die from eating the toad because they never had the ‘evolutionary opportunity’ to adapt to its powerful poison.When Cane Toads crossed the Queensland/Northern Territory border in 1983, threatening the iconic Kakadu National Park, they became a national problem, and CSIRO was invited to study ways to eradicate them. In the ensuing years, politicians increasingly realised that there were votes in efforts to eradicate Cane Toads. Government support was offered to ‘toad-busters’ for their work by the early 2000s.

Rick Shine’s Cane Toad Wars is a personal account of his scientific work with this extraordinary animal. It is a rollicking good read – written with a wry, self-deprecating humour, but deadly serious about understanding the biology of this organism and its place in the landscape. Fanned by fecundity, the Cane Toad population irrupts and spreads westward. A single female can lay forty thousand tadpoles at once and can do this twice a year. The frontier Cane Toad has longer legs than any other amphibian, even those that came first to Queensland. Shine has radio-tracked toads moving more than two kilometres per night, noting that ‘most amphibians don’t move that far in a lifetime’. ‘No other amphibian on the planet has dispersed as far and as fast as the Cane toad in Australia.’

Cane Toad wars have been waged by zealous toad-busters all the way across northern Australia, successively trying to defend their patch from the assault. In the end, it proved impossible to kill them faster than they arrived. As Shine puts it, ‘the amphibian tsunami kept coming’. The fate of people in a post-toad world became the subject of leaps of the imagination, with toad-busters pressing the urgency of their work on politicians in the hope of support. Citizen science is crucial to cane toad management, but it had to be better informed. Shine’s work was not just in toad-busting but also in myth-busting.

Cane Toads at the Meringa Sugar Experiment Station in North Queensland (photo by Queensland State Archives)

Cane Toads at the Meringa Sugar Experiment Station in North Queensland (photo by Queensland State Archives)

‘As the alien amphibians marched toward the site’ where his reptile research had been based for twenty years, Shine seized his opportunity. The Cane Toads were coming, but to a place where there was well-documented information on native fauna. He set up operations at the prosaically named Middle Point, near Fogg Dam. Originally established as an agricultural research station to support a failed enterprise in growing rice, Middle Point’s more important contributions were to the life histories of magpie geese (which ate the rice) and later to snake biology. In 2005, Shine won a major grant to study Cane Toads. Team Bufo was born. ‘Rather than just documenting ecological carnage … we had stumbled across a superb “model system” to look at evolution as it happens.’

Shine worked on evolutionary processes, heritability, and ecological change, and on managing the vulnerable native animals, not just the toads. His most unexpected work was in environmental politics and ‘the bizarre circus that plays out at the intersection between science and society’. Toad science has been shaped by the need to communicate findings for international journals like Nature and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. But its social context is profoundly local. Active toad-busters were watching their every move, and sometimes popularity obstructed science. As they experimented, the scientists feared headlines like ‘Boffins Undo Toad-Busters’ Good Work’. Yet, Shine argues, his science was improved by the need to explain his work to people who understood toad behaviour but were unfamiliar with biological principles. He kept puzzling about the accelerating rate of toad dispersal. This led him beyond orthodox evolutionary theories of change over time, to consider evolution over space – he calls this ‘spatial sorting’. Cane Toads were at the vanguard of this idea, but further evidence now comes from South African starlings, Chinese vines, and North American pine trees. Even cancerous tumours may have adopted a ‘spatial sorting’ strategy to disperse dangerously in a body. Cane Toads have become a building block for basic science, not merely a pest to eradicate.

Author Rick Shine with a cane toad (photo by Terri Shine)

Author Rick Shine with a cane toad (photo by Terri Shine)

Read this book if you want to learn about spatial sorting and the remarkable adaptations toads achieve. Yet it is also a deeply cultural book, exploring life in unlikely and inhospitable parts of the tropical north of Australia. The frontier stories are of toads, of native animals learning toad aversion, of scientifically inclined humans living with toads and crocodiles (and fierce bantam roosters). The social context is key to understanding how the scientific ideas emerged.

In 2016, the Prime Minister’s Prize for Science went to Rick Shine and Team Bufo. It was a fitting tribute to their evolutionary biology, practical conservation science, and tropical ecology. It was also a cultural prize for managing the animal that most represents the unnatural in the popular imagination. This is a book for and about Australians. Despite the American publisher and the toad on the cover, its big story is the nexus between invasive species management and Australia’s identity.

Comments powered by CComment