- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I should make it clear at the start of these discursive memories that I knew Ted Hughes only slightly and Sylvia Plath hardly at all. But I lived in fairly close proximity to their ascent to fame in the 1950s and 1960s and knew much more closely some of the personalities intimately involved in the crisis in the lives of these two remarkable poets ...

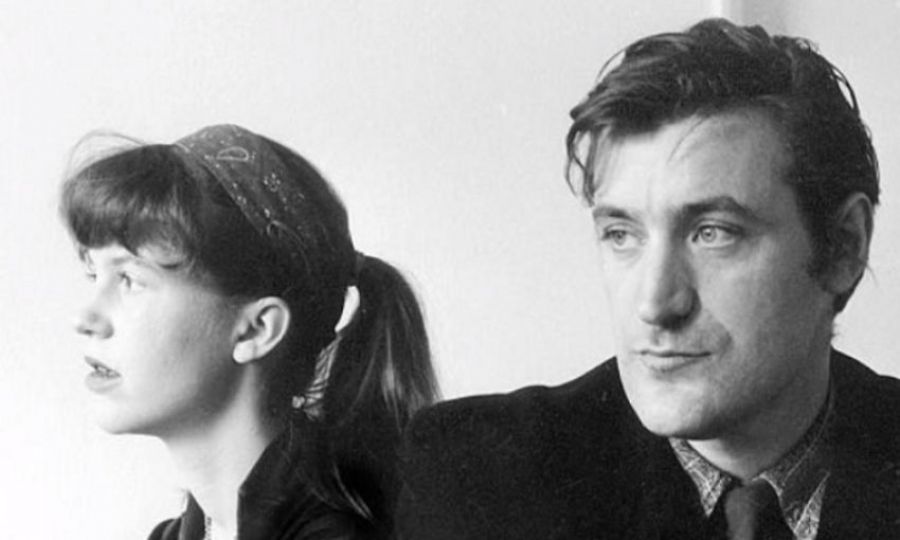

Sylvia Plath with her son Nicholas Hughes in 1962 (photograph from Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections)

Sylvia Plath with her son Nicholas Hughes in 1962 (photograph from Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collections)

After three years in London – 1951 to 1954 – I spent ten months back in Brisbane and returned to England in November 1954. My career as a poet can be said to have begun or, more properly, to have revived, from that point on. Through Katherine Morison, a Boston writer related to both T.S. Eliot and Robert Lowell, I met a young poet just down from Cambridge named Julian Cooper. Julian came from an English family long resident in Argentina. At Cambridge, he had become part of a group of writers centred on Philip Hobsbaum, a Downing College undergraduate and follower of F.R. Leavis. These aspirants were quite unfazed by the prevailing severity of Cambridge: they believed that contemporary poetry mattered. Thom Gunn had been up a year or so before, and over at Oxford the influence of slightly older poets such as Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis was beginning to be consolidated, chiefly in the several metropolitan journals they were now being printed in. They were christened the Movement, an anti-heroic and defiantly unromantic set often seen as a natural expression of postwar shrinkage in British confidence.

Hobsbaum and his companions were opposed to the prosaic tone of Movement poetry other than Larkin’s, though they shared with it a fondness for realism and social satire of a disgruntled kind. Only later, when the individual personalities of what became known as the Group developed, did a more animalistic, even shamanistic, convulsion become associated with their poetics. By the beginning of 1955, Hobsbaum’s Cambridge group was convened afresh in London. Besides Hobsbaum, the dominating personality of that first Group was Peter Redgrove, a poet of great originality who had come up to read Natural Sciences, but had deviated into verse instead. In many ways, Redgrove and Hughes were alike: they shared a galvanic approach to poetry, a sort of Blakean, perhaps even Versalian analytic energy. Ted Hughes, though never a proper member of the Group, found himself championed by it. It was apparent to me when first I joined that to see Hughes as an already mature and original poet was an article of faith demanded of all Group members.

Hobsbaum’s reconstitution of his Cambridge Cenacle took place in a basement flat in Kendal Street, off the Edgware Road. Soon the Group began to acquire new members, the most significant being Martin Bell, George MacBeth and Alan Brownjohn. I have written about Bell in my Introduction to his Complete Poems (Bloodaxe, 1988) and refer any reader to my account of this brilliantly erudite man, so much the counter in my mind to the Group’s anti-intellectual tendency, its Lawrentian Animism, a tendency which grew on Hughes in later years. MacBeth, too, and Brownjohn kept the Group rational though not unimpassioned. I stress this as we all of us, nonetheless, were paid-up admirers of Ted Hughes in his brilliant advent on the poetry scene.

It still surprises me how ready we were in those days to beard powerful literary figures in their dens – editors, publishers, and polemicists such as Alan Pryce-Jones, editor of the Times Literary Supplement; and G.S. Fraser, guru of the New Statesman as well as the TLS, a man described by Donald Davie as the chief provider of highbrow taste to the Community of Letters. Davie claimed that ‘Literary London’ had to get by each year on three of Fraser’s aperçus. Emerging powerpoints were solicited as well: the Spectator’s and Time and Tide’s arbiters, and the young Karl Miller, just beginning his ascent to the important literary editors’ chairs in London. Redgrove and Hobsbaum were tireless in their promotion of Ted Hughes’s poetry. They were entirely altruistic; it seemed to both that the future of poetry in Britain was dependent on Hughes’s work being established as the true model for the age.

Ted Hughes (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Ted Hughes (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

I can recall only one visit by Hughes to Kendal Street. He said very little during the overly serious discussion, but he intoned Hopkins’s ‘Dreadful Sonnets’ in sepulchral tones. His work had appeared in few places at this time, but he was already a palpable presence. At least once, a selection of his poetry appeared on Group worksheets, pages distributed a week beforehand to members to facilitate critical response. There we encountered for the first time some of the characteristic poems which created a sensation in The Hawk in the Rain: ‘Macaw and Little Miss’, ‘Famous Poet’, ‘Fallgrief’s Girlfriends’ and ‘The Martyrdom of Bishop Farrer’. Redgrove’s and Hobsbaum’s proselytising did not have much effect on London editors – when Hughes left for America in mid-decade he remained stubbornly unpublished in his homeland. Nevertheless, he was able, even at this juncture, to make a decent living without working too hard at any task he didn’t fancy. He had some sort of near-sinecure researching stories for a film company.

The Group went on in its gentle uninfluential way while Ted Hughes was making his name in America and becoming deeply involved with Sylvia Plath. There have been many accounts of his emergence as an exciting new poet, together with the romantic burlesque of his and Sylvia’s falling for each other, including the bloodshot chiaroscuro of the first half of Birthday Letters, and various portrayals in Plath’s diaries and letters home. I don’t question the truthfulness of such legendary happenings, as I was not in touch with Hughes’s career or his poetry after his departure for the United States. He swam back into our ken, in a splendidly certain way, after his success in a poetry competition sponsored by the New York Poetry Centre, and its immediate sequel when Faber & Faber published his winning volume The Hawk in the Rain in 1957.

It was at that point also that Sylvia Plath entered our awareness. Hughes was quickly translated into a celebrity. By the end of the 1950s Ted and Sylvia appeared in poetic assemblies in almost ‘Charles and Di’ radiance, the youthful princelings of romantic promise. At one of the yearly parties for The Guinness Book of Poetry, I watched while this ideal couple walked into the room and received the homage of several distinguished elder poets who clearly were seeing Shelley plain. One even appeared to touch Hughes as if in simulacrum of the cure for the King’s Evil – in his case, the drying-up of inspiration. Philip Hobsbaum had surrendered the Group, its meetings and worksheets, to Edward Lucie-Smith at the end of the 1950s. Hobsbaum’s vintage years had been in the inelegant South London suburb of Stockwell, and Lucie-Smith presided in fashionable Sydney Street, Chelsea. The Group was on the up and up, and a number of us benefited from the influence of its more prominent members. Neither Hughes nor Plath came to its meetings. But one recruit who became a well-liked and admired attendee was the Canadian poet David Wevill. He was fated to be a vital player in the story of Ted and Sylvia.

Wevill had been born into an international family in Tokyo, was raised in Canada and came to Britain to study at Cambridge. When he arrived, the name of Ted Hughes was already a numinous one for him as it was for all Group members. On the ship en route to Britain in the mid-1950s Wevill met a beautiful woman named Assia Lipsey. Wevill was perhaps the most handsome man I have ever known, and it was natural enough that he and Assia should fall for each other.

Assia WevillSince Assia is an essential person in the story of Hughes and Plath, she requires a reasonably full introduction. There was much about her which was mysterious: she cultivated a sense of strangeness and would have fitted into a pre-war novel of the Christopher Isherwood or Anthony Powell sort, a distinguishing presence and a fatally attractive spirit appearing and disappearing in people’s lives. Assia was half-Russian Jewish and half-Lutheran German. Her father had studied medicine in Russia and fled the country after the Revolution. He settled in Berlin where he married a Protestant nurse. Assia was born, I have always believed, in 1929. Although only her father was Jewish, the family migrated to Israel in the Nazi era. Assia was raised there during the war and educated, at least in part, by Presbyterian nuns (if such exist: this was her version of how she had picked up her perfect Mayfair English). After the war and the emergence of independent Israel, her father took her to Canada. Her mother disappears from my account of her life story at this point. Aged eighteen, she was married through a Jewish marriage broker to a young Canadian. This is the version I was given: I cannot guarantee its accuracy. That marriage did not last long. By the time she met Wevill on the boat, she was married to a Canadian economist, Dick Lipsey, who was travelling to Britain to take up an academic post. This was Assia’s first encounter with the world of London and of English upper-middle-class life, a domain into which she fitted perfectly.

Assia WevillSince Assia is an essential person in the story of Hughes and Plath, she requires a reasonably full introduction. There was much about her which was mysterious: she cultivated a sense of strangeness and would have fitted into a pre-war novel of the Christopher Isherwood or Anthony Powell sort, a distinguishing presence and a fatally attractive spirit appearing and disappearing in people’s lives. Assia was half-Russian Jewish and half-Lutheran German. Her father had studied medicine in Russia and fled the country after the Revolution. He settled in Berlin where he married a Protestant nurse. Assia was born, I have always believed, in 1929. Although only her father was Jewish, the family migrated to Israel in the Nazi era. Assia was raised there during the war and educated, at least in part, by Presbyterian nuns (if such exist: this was her version of how she had picked up her perfect Mayfair English). After the war and the emergence of independent Israel, her father took her to Canada. Her mother disappears from my account of her life story at this point. Aged eighteen, she was married through a Jewish marriage broker to a young Canadian. This is the version I was given: I cannot guarantee its accuracy. That marriage did not last long. By the time she met Wevill on the boat, she was married to a Canadian economist, Dick Lipsey, who was travelling to Britain to take up an academic post. This was Assia’s first encounter with the world of London and of English upper-middle-class life, a domain into which she fitted perfectly.

Whether the Lipsey marriage was already on the rocks or Assia and her husband gave each other freedom of action, I don’t know, but she soon became a familiar figure at Group meetings, usually accompanying David Wevill. She and David became close friends of mine and soon afterwards of Jannice Henry, who later became my first wife. David and Assia were in a considerable quandary. After he came down from Cambridge, he could not get a job, while Assia was still officially living with her husband. David eventually took up a teaching post in Mandalay, Burma. I remember spending an evening with Assia wandering through Bayswater planning her next move. Her dilemma was whether to leave Lipsey and follow Wevill to Mandalay. I had visited Assia for a weekend where she and Lipsey lived in a rural cottage in Hertfordshire in uncomfortable tolerance of each other. While her uncertainty continued, she took a job as a secretary to a copy chief in a London advertising agency, a past she returned to after her brief interlude in Burma. She had decided to divorce Lipsey and join David in Mandalay. Colonial British society was disapproving of illicit liaisons, so they had married as soon as they could. Mandalay was not a success; by the beginning of 1959, the Wevills were back in London. There Assia was instrumental in getting me a job as a copywriter in her agency. This was Notleys (later to be absorbed by the notorious Saatchi & Saatchi) in Berkeley Square, where a host of writers and other artists also worked, including the novelist William Trevor, who became a close confidant of Assia’s. There was a realistic basis to the romantic myth of creative artists working in advertising: simply that advertising was one of the last resorts of the unemployable. Most of us were not Bohemian, merely in need of employment. I joined Notleys in April 1959, by which time I had just started publishing poems, being a late developer.

Such was the position at the start of the 1960s: the Group was in full swing and Hughes and Plath were the toast of the poetry world. In 1961 I married Jannice Henry, and David and Assia were settling down in London. There was a general air of expectation, perhaps only among ourselves. We were in our early thirties, a time when anxiety begins to be overthrown by ambition and confidence. In 1960 Hughes published Lupercal and Plath her first collection, The Colossus. Lupercal was an extraordinary success and went a long way to establish the Hughes signature in the mind of the public. Here were ‘Pike’, ‘Hawk Roosting’, ‘A View of a Pig’ and dozens more poems which became the academic fodder of generations of English schoolchildren in the subsequent decades. On the other hand, The Colossus, though it attracted a few admiring reviews, went largely unnoticed. I bought my copy for £1 when it appeared and sadly sold it for £360 fifteen years later. (Today it would fetch £1,000.) I admired the poems, especially ‘Flute Notes from a Reedy Pond’, but I failed to spot her outstanding originality. Few critics guessed at the time what an extraordinary development was to follow in the years that remained to her.

Peter Porter and his wife, Jannice, on their wedding day in 1961 (photograph supplied)

Peter Porter and his wife, Jannice, on their wedding day in 1961 (photograph supplied)

It has always been difficult to find accommodation in London if you want only to rent and not take out a mortgage. My wife and I had moved down to the dark and airless basement of the house where we had been sharing a ground floor flat with Jill Neville in the Bayswater square where I still live. We were pleased enough to have a place of our own at an affordable rent. David and Assia continued flat-hunting, which was what brought them into the Plath–Hughes ambience. They answered an advertisement in the Evening Standard for a flat in Primrose Hill. When they turned up to inspect it, the incumbents showing them round were Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Wevill was delighted to meet a poet he had always admired, and Ted was immediately struck by Assia’s beauty. The two couples quickly became friends.

Hughes hated London and, though born in West Yorkshire and seeming to many people the epitome of Yorkshire ruggedness (‘the Heathcliff de nos jours’ and ‘the Penine Chain which got up and walked’), he preferred the more quietly pastoral landscape of Devon. His poetry is so strongly identified with the countryside in both its atavistic and occasionally its lyrical aspects that critics do not generally perceive what a civil and worldly character he was. Only Moortown of his many collections of poems is preoccupied with the harder and more practical side of his ‘Georgics’, and it would be untrue to speak of him as a farmer or even as any sort of adept of commercial agrarian life. There was always a fabulist’s tendency in his writing, as revealed in Crow, Cave Birds, Wolfwatching and Season Songs, and in his enthusiasm for the poetry of Basko Popa and assorted other Balkan mythmakers. Throughout his life he made his home in Devon, only indulging in forays into the metropolis for literary and amatory reasons.

There is ample evidence that Hughes appeared to women of all kinds as ‘the daemon’ destined to change their lives. On face value this was simply his urge to go to bed with as many women as possible: I once read a report he sent to the Arts Council suggesting the setting-up of a special rendezvous for poets in the capital. Its central argument was a facetious proposal for providing facilities for poets to meet and make love to a special corps of handmaidens assigned to the task of catering to the masculine muse. This was a joke, but much of Hughes’s conduct supported a literal interpretation of the notion. The other parties to his affairs tended to feel that they were involved in the highest reaches of shamanism. To Sylvia and Assia, his fascination proved fatal, especially as each was a highly competitive person. There was something of the story of Semele in their fates: they were consumed by the god’s fire when he revealed himself fully to them. Yet this myth doesn’t properly suit since, as a form of Semele, Sylvia burned with a brighter flame than the god himself. With Assia, the combustion was slower and more tortured, since it was accompanied by an intense jealousy of the rival she replaced.

From the start of Hughes and Plath’s partnership, their dual and duellistic careers as poets made each aware of the power of the other. Hughes has left a convincing account of how horrified he was when Sylvia showed him her just completed poem ‘The Moon and the Yew Tree’. It is almost a ground plan for self-destruction. But Sylvia, in that delight that attends poets when they know they have just written a masterpiece, could see only the glory of her creation and not what it portended. It has always seemed to me that Hughes, though formidable, was not as strong and imaginative a force as Plath. He could turn himself, Tarnhelmlike, into a shaman and a delineator of divine madness, but was only mad nor’ nor’ west, possessed of a kind of calculated exaggeration. His peculiar book on Shakespeare is really an attempt to dismantle the good sense of a supreme writer, who, despite possessing great gifts, never degenerated into extremism. If Hughes could show that Shakespeare was as weird in his beliefs as he himself was, then he could justify his own performance with its calculated violence of effects. He couldn’t do this, and his poetry, from Lupercal onwards, became more and more a matter of issuing large emotional cheques with no deposits in the bank to support them.

At the end of his life, especially in his Ovid imitations and his remaking of Greek and Roman tragedies, notably the Alcestis, all appropriateness had been lost. There is little left but wild over-emphasis, a garish array of language playing a searchlight on the farther shores of potent myths. Plath, at first sight, seems an even more exaggerated writer than Hughes, but there is always a still centre of truth in her finest poems, a lack of attitudinising vulgarity, even when she is harnessing Hitler and Hollywood to her argument. Leaving Plath must have been not just an imperative for someone who wished to love other women whenever it suited him, but also a move to defend his own talent from competition with a superior one. Such a notion might seem doubtful given the greater recognition he enjoyed than she did, but it is one which has begun to convince readers of her poetry since the true scale of its achievement has become known. Judging the completed course of the two poets’ productions, it is tempting to see Hughes’s attitude as resembling Alexander Pope’s Turk, who will suffer no rival next to the throne.

During 1962, Hughes’s affair with Assia developed. David and Assia were invited to the Devon home stead several times. Although my wife and I saw the Wevills quite often in London, we did not know the full extent of Assia’s involvement with Hughes. David remained throughout the whole affair a model of reticence and dignity. He was appalled, but he loved his wife and he respected Hughes as an artist. Hughes left Sylvia in the early months of 1962, although he continued to live largely in Devon. Sylvia came back to London and began what was to become, in its short projection, a highly successful career as a freelance writer. She started to broadcast for the BBC, wrote plays and features, and began mixing in her own right at literary parties. Hughes had always avoided the public side of literary life, though he was not indifferent to reputation and networking.

Ted Hughes and Assia Wevill with their daughter, Shura

Ted Hughes and Assia Wevill with their daughter, Shura

It was during the busy months of the second half of 1962 and the first two months of 1963 that Plath wrote the remarkable group of poems on which her reputation rests, a harvest comparable to Keats’s desperate flurry of 1818. To the eye of the casual attendee of functions, she was adapting to the separation from Hughes very well. There was always a terrier-like enthusiasm in Sylvia, a sort of All-American competence masking her deep-seated vulnerability to mental instability. Only one or two people could have anticipated how swiftly she was moving towards the crisis that killed her in February 1963 – perhaps Hughes himself, some immediate friends and neighbours in Devon, and Al Alvarez, to whom she showed her latest poems as they were written. None of these, however, except for those few who were aware of her history of mental collapse, had sufficient cause to anticipate what happened. Readers of The Bell Jar, published under the pseudonym of Victoria Lucas, would hardly have seen it as a more personal text. I remember encountering her at a PEN party in Chelsea in December 1962, the only occasion on which I talked to her for more than a few minutes. She seemed febrile and brightly engaging, but both my suspicions and my loyalties were aroused. She made tentative arrangements to ring me in the New Year to meet for lunch. She was straightforward about why she wanted this meeting: she knew I was a friend of Assia’s and she wanted to pump me about her rival. For the same reason, I prevaricated. The luncheon call never came. I was Assia’s friend and, while I suppose I appreciated that Sylvia was the injured party, I was inclined to put the whole blame on Hughes.

The New Year set in with constant snow and extreme weather conditions all over Britain, none worse than in London. For three months thereafter, ice and snow were impacted across the entire London area. To get to Hampstead from Bayswater you felt you needed the skills and huskies of Captain Scott. In February, Alvarez gave a party at his home in Hampstead to which Jannice and I were invited. Jill Neville was Al’s girlfriend at the time (he describes these fraught days in his recent autobiography Where Did It All Go Right?). Jill had been deserted by her first husband soon after her marriage in 1960, and her daughter lived with her.

I saw Alvarez quite often at that time, usually when we were babysitting for Jill. I can certainly endorse his own account of his reaction to the poems Sylvia was bombarding him with. Her production rate of poetry was often several new works a day. Had she still been with Ted, no doubt she would have shown them to him as soon as she finished them. She was quite confident of their quality, indeed of the originality of what she was writing. But her exhilaration was liable to periods of acute depression. Her monitor, her loved and hated companion and colleague, the one she trusted as measurer in the assessment of her work, had deserted her. There was only her professionalism to keep her in any sort of balance. Meanwhile, what was to be done with the great poems she was producing? It was precisely a watertight bulwark between the fearless subject matter of her art and the personal despair of the feelings which produced it that she lacked. Sylvia was a genius but she was also a distracted human being. Such a writer can face the dreadful determinants of existence head-on in poetry yet be unable to bear the weight of feeling in her living person. In Alvarez, she was lucky to have a friend and critic of quality who could recognise the power of what she was writing. But he was not a miracle-worker and did not fully appreciate how desperate her state of mind had become. Further, she was looking to him as at least a potential lover, someone to take the place of Hughes as resident critic and inspirer. In poems such as ‘Lady Lazarus’ and ‘Daddy’, and the rest of those fierce confrontations of her father, Otto Plath, and Ted Hughes, which flared so brightly when they were published posthumously in Ariel, she was fighting her family demons over classic ground.

Alvarez must have known that even if he took Hughes’s place he would have to live with the material of Sylvia’s life being aired so terrifyingly in the spate of poems she was showing him. He had his own problems. His liaison with Jill had run into difficulties. Also, observing as he did the increasingly prospering ascent of Plath to public acceptance, he must have thought her luck was changing and that she would soon be able to settle into a stable existence, one in which she could compete with Hughes on something more like her own terms. Already the BBC was employing her. Even during her lifetime, she broadcast many of the poems collected in Ariel. The opposition of hope and despair in her mind was stark. Perhaps she could have survived if circumstances had not gathered in a temporary but seemingly unavoidable way. She was looking after her children, Nicholas and Frieda; she was holed up in an unspacious flat in unneighbourly London; the appalling weather restricted hers and her children’s freedom of movement; and she was free to imagine Ted and Assia patrolling a world which had been her own domain. One can speak of ‘pathetic fallacy’ being operative — that state of mind in which the outward circumstances of life appear to be echoing the turbulence of an inner landscape. I suspect, also, that she was seeing or seeking to see Hughes whenever she could.

Sylvia Plath writing to her mother, Aurelia Plath Lilly, on 6 November 1960 (photograph via the Lilly Library, Indiana University of Bloomington)

Sylvia Plath writing to her mother, Aurelia Plath Lilly, on 6 November 1960 (photograph via the Lilly Library, Indiana University of Bloomington)

I am unsure of the exact sequence of events during those fatal two months of 1963. In a recent piece of fiction, Emma Tenant, who had already portrayed Hughes in a memoir as a destructive Dionysian force, has suggested that Assia and Ted visited Sylvia immediately before her suicide, and that Assia was pregnant. Certainly, Assia terminated a pregnancy around this time, as I possess a letter she sent to my wife thanking her for her help in the convalescence from an abortion. The letter is undated. Tenant’s suggestion seems unlikely, but accounts of Sylvia’s last days vary. I had expected to see her at Alvarez’s Hampstead party. It was only a day or so later that news of her death was published in London. She had gassed herself, but she took care to protect her children.

The ice finally melted in London but the figurative chill around Sylvia was never to thaw. The shock of her death took a while to sink in, especially as very few of the circumstances were revealed. I fear that Jannice and I were chiefly concerned at what would happen now to David and Assia. At first it seemed as if Hughes and Assia could live together, but their union quickly ran into trouble. This was basically a clash of personalities and of preferred ways of living. Assia hated the isolated life which Hughes led in Devon. Perhaps complete isolation might have been acceptable, but Hughes installed his family, and Assia had to endure the continuous hostility of his mother. She also felt, however obscurely, that Sylvia had beaten her, that her suicide was the winning stroke in their competition, however disastrous for the one who made it. The dead woman became a more formidable presence than the living had been; such resentment grew exponentially once Plath’s posthumous reputation bloomed after Ariel was published in 1965.

Hughes chose the poems in Ariel from among those left behind in Sylvia’s archive. It was a brilliant distillation of her genius and remains to this day one of the finest collections of poems published in the twentieth century. Perhaps the more celebrated dances of death are beginning to seem a little overblown, but poems such as the Bee Box sequence, ‘The Moon and the Yew Tree’, ‘Berck Plage’, ‘Tulips’, ‘Sheep in Fog’ and ‘Edge’ have lost none of their force. At intervals in the years that followed, further instalments of Plath poems, beginning with ‘Crossing the Water’ in 1971, were issued by the Hughes estate, many of which were very fine, though no subsequent single volume quite equalled Ariel in intensity. The Bell Jar reappeared under her own name, and in spurts and spasms in the forty years that have elapsed since her death almost everything she wrote has been published, including her letters home, various journals, pieces of radio work, stories and autobiographical fragments. Books galore have been written about her. The main mystery remaining is what else she wrote. Hughes admitted he had destroyed one book of diary entries to protect their children from the pain of reading about their mother’s acute unhappiness. In view of the poetry which Frieda Hughes now writes, this caution may seem unnecessary. Also one incomplete novel disappeared.

The manipulation of Plath’s creative work at the hands of the Hughes estate (not just Ted but also his sister Olwen who acted for years as literary agent and Cerberus of Plath manuscripts) is complex and hard to unravel. The most thorough examination of what happened is in a chapter on Plath’s posthumous publication details in Jacqueline Rose’s study The Haunting of Sylvia Plath (Virago, 1991). The policing of comment in Plath’s life and work by the Hughes estate has been extremely severe. When Anne Stevenson wrote her biography of Sylvia, she had to clear every reference with Olwen Hughes on penalty of not being able to quote any of the poetry. One must set this against the many unpleasantnesses addressed to Hughes by individual commentators who pestered him throughout his life. The only question that remains at stake today is the persistent rumour that Hughes also destroyed some of the poems he found among Sylvia’s manuscripts. Perhaps the answer to this lies in his papers sold to an American university. Posterity may find out.

Peter Porter and Jannice Porter with their daughter Katherine in 1965 (photograph supplied)

Peter Porter and Jannice Porter with their daughter Katherine in 1965 (photograph supplied)

Jannice and I rather lost touch with Assia in the years that followed Sylvia’s death. She became pregnant for a second time and gave birth to a child they named Shura. But domesticity with Hughes seemed never to work well for her. For some time after Shura’s birth she lived on and off with Wevill, who maintained the fullest privacy about his and her marital circumstances, and helped look after the child as his own and even adopted the role of father. Assia seemed to have had no intention of abandoning Hughes, though equally certainly she was not happily ensconced with him. She had always been very accomplished at European languages and began to take up the translation of poetry, mostly from German and Hebrew. Unfortunately, she knew she could not compete directly with the dead Sylvia on poetic ground. Hughes was attracting the hostility of angry feminists. Finally, David Wevill had had enough. He decided to return to North America, ending his relations with Assia. He had published a number of books of poems and had received support and admiration from many writers in Britain, together with an Arts Council bursary to continue writing. I don’t doubt that he still loved Assia but was determined to break out of the Dantesque storm he, Assia and Ted were wrapped up in. He now teaches Literature in Texas and has cut himself off from his life in Britain. I can only guess at what these terrible years cost him in personal misery.

Hughes’s own publication rate during the decades of the slow building-up of Plath’s canon was continuous. He began an excellent revenue-raising way of releasing his work to the world. He built up a worldwide list of wealthy subscribers who were given first and exclusive (for a time) sight of his latest productions. Eventually, public issues of these privately circulated books were made and usually favourably reviewed in the press. Alvarez had made him the key English figure in his polemical anthology The New Poetry (Penguin, 1964). In its editorial, he wrote of the need to get beyond what he described as ‘the gentility principle’. This meant subscribing to American audacity and avoiding more seemly British tones. Hughes was projected as the chief agent in this necessary purgation. He and other galvanists (though not Larkin and the Movement poets) would take up the ‘Confessional’ baton from Robert Lowell and John Berryman. Increasingly, I worried that Hughes’s poetry was becoming composed from hard cases: he seemed fonder of writing for children than for adults. Powerful as much of his poetry remained, it spoke to the margins of emotions: it sought opportunities for extremism. Language was to be seen at its best only when it writhed. Wodwo had strong sections, but overall was a gallimaufry of violent effects. Crisis was reached with Crow, which originally had had a widely scanned vision parallel in some ways to such epics as Gilgamesh, but which degenerated into a set of comic-strip adventures, a celebration of the doings of Death, half ritualistic or liturgical, and half Tom and Jerry and The Simpsons. Hughes’s friend, the illustrator Leonard Baskin, contributed to this Totentanz aspect with his fierce night-black images. I reviewed Crow in The Guardian and acquired some notoriety for suggesting that British poetry would be unable to avoid ‘the black shadow of Crow falling across each poet’s page’. I mention this to stress that I was as active as anyone in the Fourth Estate in praising Hughes’s work, and that I am now probably exaggerating my disillusion with the bulk of his poetry as a belated mea culpa. By the end of the 1970s I had begun to be seen by the Hughes camp as a natural enemy. Olwen Hughes told a friend of mine that I couldn’t review Così fan tutte without dragging in a hostile reference to Ted Hughes. I still believe that he changed from an original and formidable poet into a near-caricature of extravagance chiefly through arrogance and masculine predatoriness. His manner too often appeared to bully all sense out of his subject matter. A steady stream of overdone works appeared – collections such as Gaudete, a truly blood-soaked extravagance – and it was only towards the end of his life that he seemed to redeem himself with Birthday Letters. Certainly, Birthday Letters is not spoiled by the inappropriate coarseness of his translations of that elegant poet Ovid. His Ovid versions won rapturous acclaim by English literati who seemed to know little of Ovid’s formal decorum. Hughes was by now receiving that apparently inevitable accolade offered by the English to their surviving masters – he was being put on the stamps, as it were, given a leg up by the Lion and the Unicorn. With his appointment as Poet Laureate, he became official British Art.

There were a few other signs of a more hopeful kind. Towards the end of the 1970s, a single poem that appeared unannounced in a selection of his work pointed to a desire to return to the subject of his life with Sylvia, a topic he had kept at arm’s length ever since her death. This rational and moving poem was entitled simply ‘You Hated Spain’ and covered their visit to that country in the 1950s. Plath had disliked what Hughes enjoyed, the cruel bullfighting aspects, and the poem showed a welcome understanding of her point of view. This poem is now eighteenth in the sequence that makes up Birthday Letters. It was knowledge of his cancer that sponsored Hughes to try to record those events of so long before, to present at last his account of the Hughes–Plath relationship.

I find the first half of Birthday Letters an often admirable and truthful attempt to record what happened to them in both realistic and psychological terms. The end of the sequence, however, is spoiled by a return to extremism and is further disfigured by touches of racism. Such things remind the reader that the ‘Hawk Roosting’ side of Hughes hardened in later years into mystic ritual, running from salmon fishing with the Queen Mother to identification with Margaret Thatcher’s reactionary government. The most unpleasant poem in Birthday Letters is ‘Dreamers’, a portrait of Assia Wevill. It reads as though Hughes had found a scapegoat for his betrayal of Plath. Assia’s Jewish Germanness is contrasted with Sylvia’s anxious Teutonism, and the poem is laced with racist adjectives and drenched in British dislike of Central European cultural archetypes, almost as if Hughes distrusted the Brothers Grimm as much as he did Sigmund Freud. He suggests that Assia had sought them out deliberately to destroy them both. Compare this poem with Sylvia’s own conjuring of Assia in Ariel. Despite nominating her rival as being, like the moon, a ‘light-borrower’, Plath’s delineation lacks Hughes’s loaded gypsy overtones. Plath sees Assia as a hated rival, but as human. Hughes turns her into an ethnic devil.

‘Dreamers’ is particularly unforgivable since I recall the funeral of Assia and Shura in March 1969. Jannice had kept in touch with Assia from time to time in the 1960s. They had been mutual confidantes. Assia had made several attempts to live under Hughes’s roof but she usually returned to London. I saw her at a poetry reading Hughes gave at Festival Hall shortly before her suicide. She appeared to be in good shape and spoke about some translations she had made of the poetry of Yehuda Amichai, an Israeli friend of Ted’s. I was on a short tour of the Midlands when I had a call from Jannice telling me that Hughes had rung her to tell her that Assia had committed suicide and had killed Shura as well. The funeral was to be held the following day. I took a late train back to London and Jannice and I rode in the front taxi with Ted and Assia’s father to the crematorium. The memory of the two coffins waiting before the fire curtain, the one an adult coffin and the other a diminutive shape, will always haunt me. I believe our being asked to travel in the same taxi was Hughes’s tribute to my wife and her constant devotion to Assia.

Peter Porter (photograph supplied)

Peter Porter (photograph supplied)

I saw Hughes seldom after this. We both went on a British Council Poetry Tour of Israel in 1971 when he was honeymooning with his new wife, Carol. I recall that Charles Osborne and I preferred to attend an Israel Philharmonic performance of Fauré’s Requiem to a staging of The Bacchae which Hughes proposed. He had guaranteed that real blood (animal) would grace the staging. D.J. Enright and I watched a priest approach Ted and Carol in the basilica of Nazareth with the admonition, ‘Don’t cuddle your wife, this is not a place of love’.

Jannice killed herself in 1974. I am convinced that the example of Assia was always before her mind, though she had been affected by a severe bout of meningitis in 1967. In my more despairing moments, I reflect on the frequently destructive antinomy of the creative natures of men and women, but since so much of what happens to us is fixed by early childhood there is hardly any way of avoiding unpropitious marriages. Perhaps Strindberg is right, and it is human adversity which turns us into wolves.

I have made little attempt to keep bias out of this short set of memories. I feel some loyalty to the spirit of Assia Wevill, but I am parti pris for Plath against Hughes only because I am convinced that her poetry (all written before she was much older than Shelley when he died) is brilliant and truthful, while his, except in his least cluttered achievements, can be seen as brutal and overriding. There is something in the tone of modern Britain which makes Hughes a suitable figure for canonisation. His personification of power, royalty, nature and race is less and less appealing. The urbanised Muse of Larkin is preferable, and the generous expansiveness of the expatriate Auden is more attractive still. Not that nationalism and chauvinism are confined to Great Britain; they have become almost universal, as writers sense that their adoption is a fair way into the National Purse. But I think we should avoid such partisanship wherever we live. Fortunately, poetry in English need not always be dyed in nationalist colours. Looking back to happier days, I would want to pay proper tribute to the poems in Lupercal, and to those in Ariel. They are something worthwhile to take into the dark.

Comments powered by CComment