- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Book of Dawn

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dawn Fraser had a hundred or so pages of fair prose in her and she put them in this book, her autobiography. The trouble is that the book is 400 pages long. But that’s not a bad result. If a David Malouf or Helen Garner lined up for an Olympic swimming final, you’d expect them to sink.

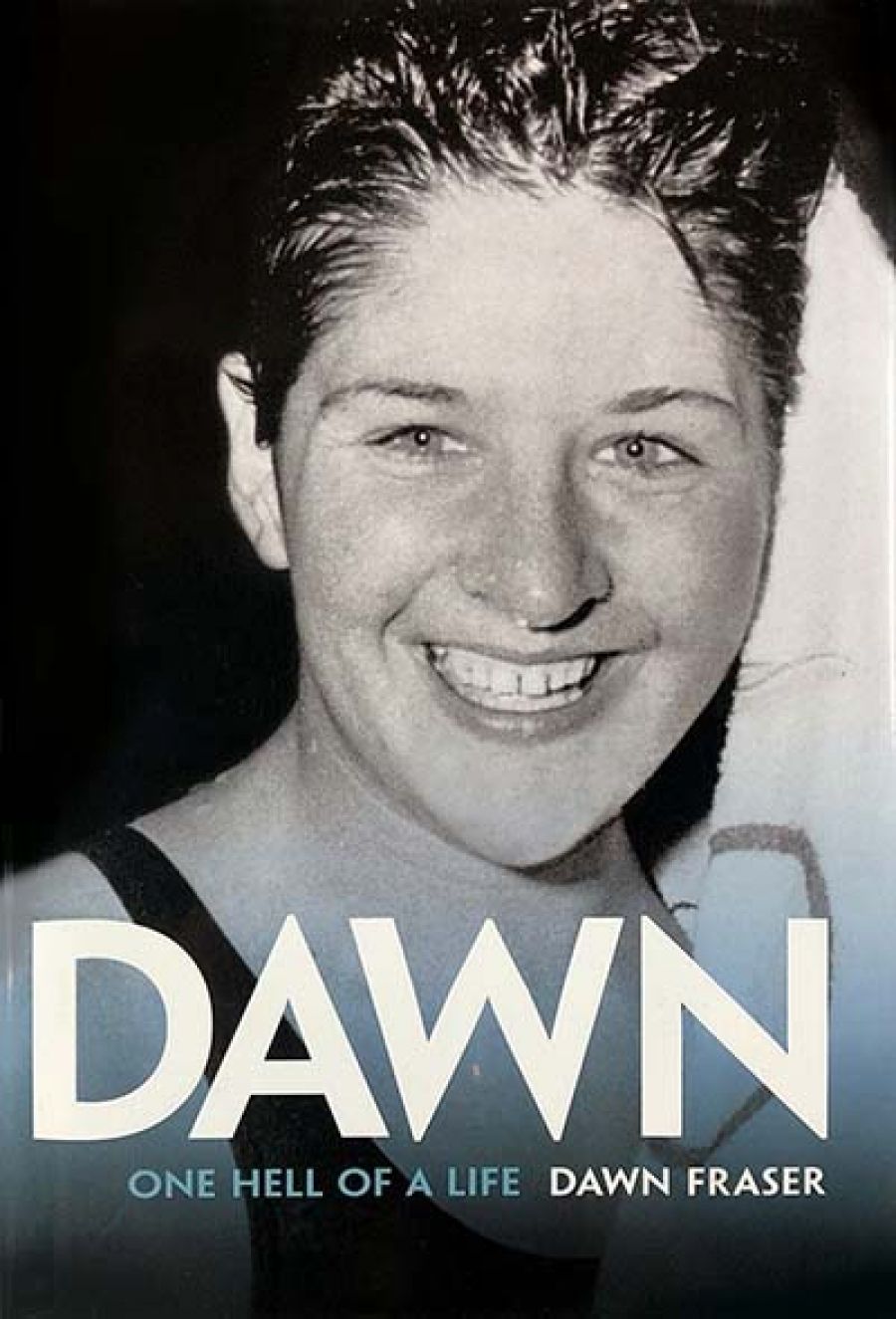

- Book 1 Title: Dawn

- Book 1 Subtitle: One Hell of a Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Hodder, $45hb, 420pp, 0 7336 1342 X

For you sports virgins, those of you who went to Tuscany rather than watching the Games, Dawn was a champion freestyler who won gold and silver medals at the 1956, 1960, and 1964 Olympics. She also had a reputation as an anti-establishment ratbag and co-souvenirer of an official flag at the Tokyo Games. She was, she is, the national Australian icon labelled ‘Our Dawn’. National sporting icons are like writers; they make a life out of their life. Writers spin and re-spin the yarn of their own selves. Sports stars bask publicly in their long-ago deeds, often becoming authors in the process. This is apparently Dawn’s second published autobiography – the first appeared years ago. She also co-scripted a Dawn film, produced in the early 1970s.

Media attention this time round has focused almost entirely on revelations (presumably fresh ones) that she was raped by a sailor in 1971 and has had lesbian affairs. The latter are briefly and shyly dealt with in the book, as if Dawn fears her readers will keel over, shocked. My old mum, an armchair prude and gossip from way back, merely scratched her bee-hive and said ‘Yawn, yawn’ when I told her about them. Dawn’s four-page account of the rape, the dramatic cornerstone of a book full of one thing going wrong after another in her life, is affidavit-like for the most part, layman’s impact statement for the rest. It is certainly among those hundred pages I was talking about. So is the first sixth of Dawn, about her childhood in Sydney. The hallmarks of Aussie icon mythology are there: family was poor and large; father was a hard man but lovable; kids did odd jobs to make ends meet (Dawn ran messages for the local SP bookie); Dawn hated school but loved to swim; every morning before class she was up at four to train in the chilly local pool in her threadbare cossie; she dreamed of making the big-time and travelling the world; she fought overbearing sports bureaucrats; then tragedy struck – her brother died, but grief spurred Dawn on to overcome, to be victorious. Her pedigree is so under-privileged she’s privileged. Had it been different, had she been the worry-free, private school daughter of blue-chip parents, well … she wouldn’t be ‘Our Dawn’, would she?

You know how British playwright Alan Bennett used Leeds idiom in his Talking Heads series to clone characters from monologues? Dawn’s book does a similar thing with her own idiom: working-class Sydney, 1930s to the 1950s. Of course, I’m not saying the artfulness is the same or even in the same universe. Dawn’s book is one long-winded monologue (she did in fact dictate the work). Let’s call it naïve writing, or accidental art. The idiom is pitch-perfect. That’s not to suggest that Dawn should take up writing full-time or book a table at the premier’s literary awards. But I give those hundred pages their due. In them she sounds just like my Aunty Dorothy, a Randwick girl, no longer with us – Dawn’s age, Dawn’s background. If my Aunty Dorothy had ever dictated a book, it would have sounded just like Dawn’s. She would tell of her ‘testing times’, how she had ‘her work cut out for her’, not overlooking the ‘sadly, sadly missed opportunities’, the ‘very, very close friends’, the ‘very, very’ hard work, the moments she was ‘really, really annoyed’, but how in the end she made her own fun and had a ‘wonderful time’. Clichés? Absolutely. But that was her language. That was her tongue. And it’s Dawn’s. To my knowledge, Aunty Dorothy never planned to kill herself nor made a pre-suicide video, as we learn Dawn did. But if she had, she would have snapped herself out of it just like Dawn, who imagined how ashamed her mother would have been of such nonsense.

Aunty Dorothy was a great one for trapping you on the settee with her photo collection: album after album of sepia granddads and polaroid bingo wins. Dawn’s no different: I counted more than 150 photos in this book, some of very poor quality, and one – a group shot of her with the Pelé, Carl Lewis, and Mohammed Ali – reproduced three times. My Aunty Dorothy was never a national icon, but even she would have stopped short of that.

My favourite Dawn quote from this book is the one about her reason for standing (successfully) in 1988 as an Independent candidate for the NSW parliament: ‘I wanted a new job at the time, and the fact that I would be paid a good salary in Parliament and that I would have the position for four years appealed to me.’ Naïve writing at its best! Add to this her tales in the last quarter of the book of her grateful, fawning hobnobbing with those oily wretches, Olympic officials, the imperious, establishment big-shots she would have despised as a sceptical youngster, and you realise that, national icon though she might be, underneath it all she’s just like the rest of us: vain, attention-seeking, desperate for acceptance, an eye on the main chance – and the odd gong if one’s floating around. In that way, she truly (truly, truly) is Our Dawn.

Comments powered by CComment