- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

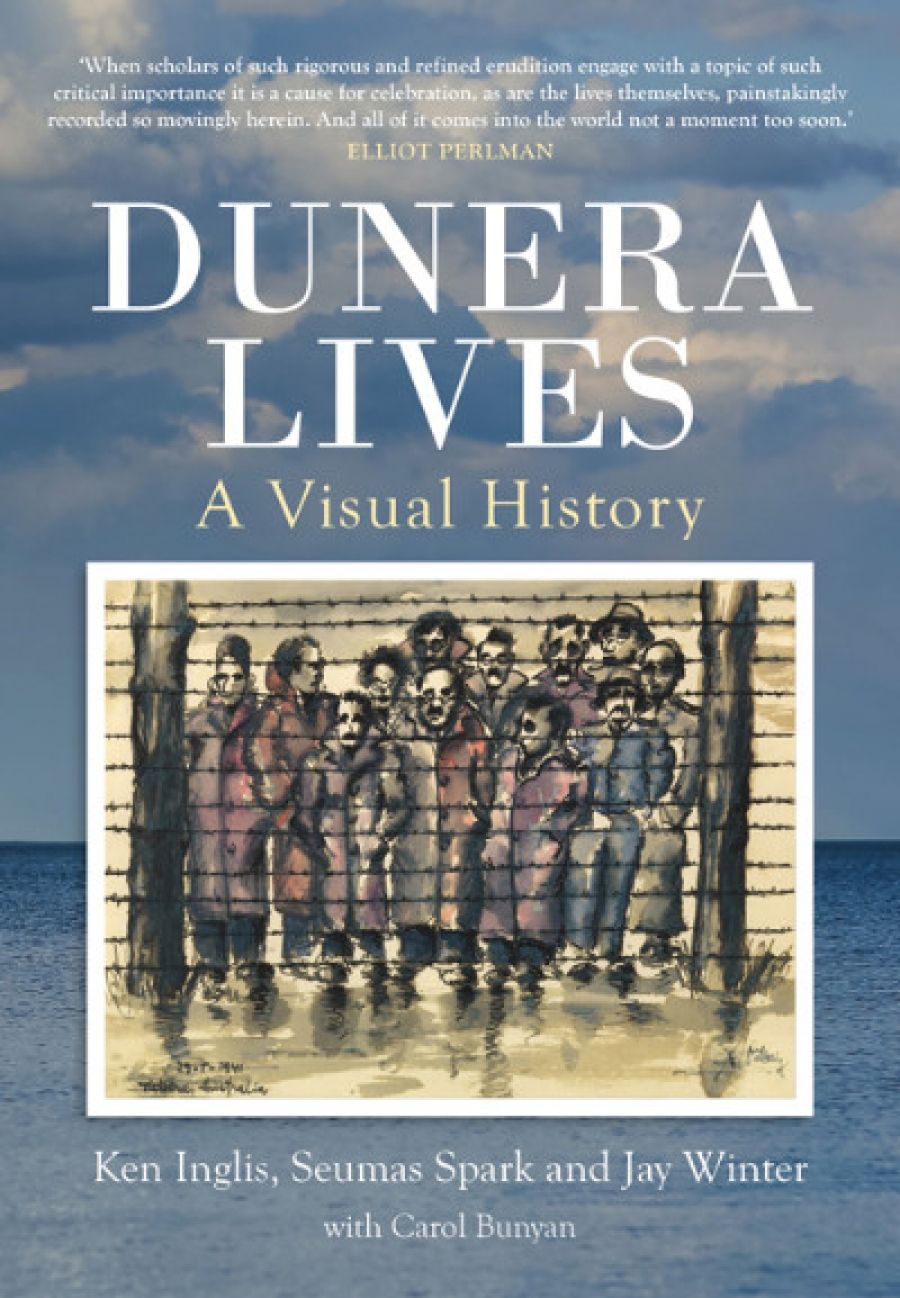

- Custom Article Title: Astrid Edwards reviews 'Dunera Lives: Volume 1: A visual history' by Ken Inglis, Seumas Spark, and Jay Winter with Carol Bunyan

- Custom Highlight Text:

Dunera Lives: A visual history is a compelling examination of the experiences of Britain’s enemy aliens within Australia’s detention centres in World War II. This evocative visual narrative of primary sources, compiled by the late Ken Inglis with Seumas Spark and Jay Winter, assisted by Carol Bunyan ...

- Book 1 Title: Dunera Lives: Volume 1: A visual history

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 576 pp, 9781925495492

The deportation from Britain of more than two thousand people who had fled Nazi Germany, and their voyage to Australia on the Dunera, is firmly a part of Australia’s history. However, the historical narrative is full of misconceptions about the ‘Dunera boys’, and the goal of this work is to correct the record. The authors achieve this and so much more. First and foremost, they were not all boys; they ranged in age from sixteen to sixty-six. Nor were they all Jewish; there were a few Nazi sympathisers in the mix. They were victims of injustice in a world at war.

(I have one burning question: what did the majority of the interns think about the few Nazi sympathisers in their midst? The primary sources do not answer this.)

Britain entered World War II on 3 September 1939 and immediately classified those who had sought refuge from Nazi Germany as enemy aliens. Many considered low risk had been allowed to continue to work in Britain; however, after military defeats in April 1940, deportations of Austrian, Czech, German, and Polish civilians began.

In a shocking colonial throwback to the earlier days of British settlement in Australia, Britain deported her unwanted souls to Australia’s foreign shores. The first ship to depart Britain with these unwanted enemy aliens was the SS Arandora Star. Although those aboard did not know, they were bound for Canada. The ship was torpedoed, resulting in the deaths of at least 800. Around 450 were rescued; a week later, barely recovered, they were packed onto the Dunera with around 1,500 others. They did not know they were headed to Australia. The fifty-seven-day voyage was physically arduous and psychologically difficult. The Dunera was an overcrowded troop transport without adequate food, accommodation, or sanitation. Arbitrary punishments and daily cruelty were the norm. At least one deportee suicided on the voyage, and another experienced a mental breakdown.

An artwork by Emil Wittenberg documenting the crowding living quarters on the Dunera. (Source and copyright: Martin Burman)

An artwork by Emil Wittenberg documenting the crowding living quarters on the Dunera. (Source and copyright: Martin Burman)

Upon arrival in Australia, the ‘Dunera boys’ were interred in rural detention camps in Hay, Tatura, and Orange. Life behind barbed wire in Australia may not have been quite as torturous as the voyage itself, but nevertheless this is a story of ‘injustice, bureaucratic bumbling, and human error’. They were Jews who had fled from the Nazi regime to the relative safety of Britain, and were then deported to the other side of the world. Australia, for its part, once again acquiesced to being used as a colonial outpost.

Not long after they were deported, the British government conducted an inquiry. The abuses aboard the Dunera were deemed an ‘error of State’, and the deportations themselves a decision Prime Minister Winston Churchill came to regret. Compensation – albeit a small amount – was eventually paid.

An image encroaching dust storms taken by Fred Harrison in the 1940s. The Dunera internees were greeted by the same storms on their arrival in Hay. (Source and copyright: David Harrison)

An image encroaching dust storms taken by Fred Harrison in the 1940s. The Dunera internees were greeted by the same storms on their arrival in Hay. (Source and copyright: David Harrison)

They were people without rights in a world at war. As civilian internees in Australia, they did not have the status of POWs or refugees. Many of the interns were released in 1942 after the policy of internment was officially abandoned. The simplest choice was to return the deportees to Britain, although many, embittered about their treatment, refused. Some returned to Britain (still at war, so the risks were high); some even joined the armed forces. Others entered civilian life in Australia as refugee aliens.

Dunera Lives reminds us how easy it is to forget the personal in the historical record. The first of many stories that stands out for me is that of Franz and Gerard Feuerstein (who became Frank and Jack Firestone in Australia), who fled to Britain in 1939. Their parents, Leon and Elise, remained in Germany and committed suicide by gassing themselves. Another story concerns the teacher Hans Joseph Meyer, who volunteered for deportation on the Dunera so as not to abandon his students, who were being forcibly deported. Most poignant of all is the proposed camp constitution written on a roll of stolen toilet paper during passage to Australia, written in German and then translated into English. The interns – remember, these were people who had fled the rise of Nazism – who drafted the constitution believed in liberal democracy. The constitution worked well enough for local camp commanders to let the interns govern themselves.

Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, not titled (Internment camp). Drawn in 1941, most likely at Hay. (Copyright: Chris Bell)

Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, not titled (Internment camp). Drawn in 1941, most likely at Hay. (Copyright: Chris Bell)

Dunera Lives is not the first work to chronicle this part of Australia’s history, but it is the first to do so after a Freedom of Information request granted access to the National Archives of the United Kingdom. Volume 2, to be continued without Ken Inglis, will add an extra layer to the complex Dunera story.

Dunera Lives is a reminder that governments make mistakes, and that injustice can be done in the name of policy. Simply by publishing this work, the authors raise the question: what primary sources will one day be compiled about life on Manus Island and Nauru? Dunera Lives is also a reminder that governments can acknowledge mistakes, a notion that seems revolutionary in 2018. Dunera Lives, while focused on the 1940s, poses questions for all Australians to ponder.

Comments powered by CComment