- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

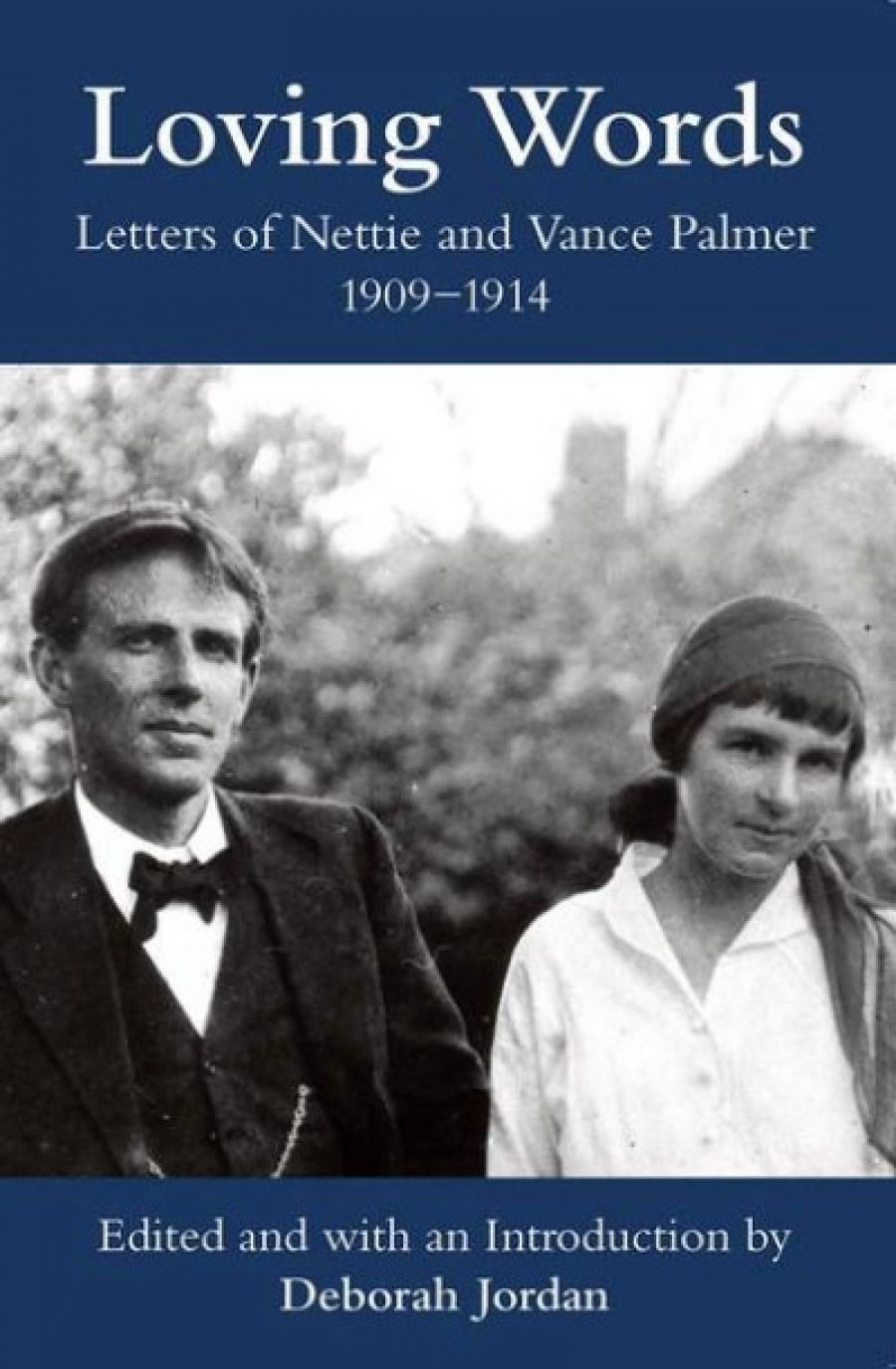

- Custom Article Title: Brenda Niall reviews 'Loving Words: Love letters of Nettie and Vance Palmer 1909–1914' by Deborah Jordan

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Vance Palmer met Nettie Higgins in the summer of 1909 in the sedate setting of the State Library of Victoria, they were both twenty-three years old. Yet even to speak to one another was a breach of convention; they had not been introduced, and Nettie at least felt quite daring ...

- Book 1 Title: Loving Words

- Book 1 Subtitle: Love letters of Nettie and Vance Palmer 1909–1914

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl & Schlesinger, $39.95 pb, 500 pp, 9780994429667

When Nettie read Vance’s early writings, she stressed the worthlessness of her literary judgement but gave it just the same. Later, Vance wrote of ‘that modesty that fits you like a familiar garment’. He accepted her rebukes for his repetitive prose and his weakness for worn-out metaphors. As a critic, she could be tough, but she turned her most consistent criticism on herself.

Nettie’s abiding sense of unworthiness makes more sense when her family context is known. Although she appears here as an only daughter with one brother much younger than herself, she was in fact a survivor of a larger family group. Catherine Higgins bore six children. Three boys died in infancy, and a second girl, Eileen, lived long enough to be entrusted to seven-year-old Nettie’s special but unavailing care. Nettie’s persistent feelings of inadequacy were formed early. Nothing she could do for her parents would ever be enough.

Nettie began her academic career well, with first class honours in her first year, but she completed her degree with an embarrassing third class. Too much time spent writing to Vance Palmer may have been the trouble. She qualified as a teacher in 1910.

When Vance met Nettie, his future seemed open; hers was circumscribed by anxious parents and by the influence of her famous uncle, Henry Bournes Higgins, judge, politician, public intellectual, and member of the university senate. Vance’s early letters were written from a Queensland cattle station where he worked as a tutor. Hers came from suburban Melbourne. Nettie’s privileged education contrasts with Vance’s unsheltered experience, but they were alike in their commitment to books and ideas. Their letters of early 1909 were inward-looking, self-searching. They were not yet love letters.

The pace quickened when, without consultation, Nettie was told that she was going to England early in 1910: ‘everything is arranged from chaperone (alas) [and] oh yes they say I may go to Ireland’. The trip was partly financed by Nettie’s uncle Henry, a towering figure in her life. Nettie longed for the freedom of anonymity, but knew that the watchful John and Catherine Higgins would exercise remote control. To her astonishment, Vance followed Nettie to England. The signature ‘Vance P’ became ‘Your mate’, and Nettie wrote: ‘Kiss me, Vance, and make me brave and steady and worthwhile.’ Chaperone and propriety forgotten, they became happy lovers.

Image of Nettie Palmer (photo by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)Marriage was still a distant prospect. Nettie went to Germany to study while Vance struggled to make a living from journalism in London. Back in Melbourne in November 1911 after her interlude of freedom, Nettie taught French and German at her former school, the Presbyterian Ladies College. Her father consented unenthusiastically to an engagement; he and her mother would have liked a son-in-law with steadier prospects, preferably in Melbourne. Vance’s lack of religious faith was against him too but, because Nettie had long since admitted that she never prayed, it couldn’t be made an issue. In the end it was a question of income. Vance had developed a useful network in London, and he told Nettie that poverty was easier to endure there than it would be in Australia.

Image of Nettie Palmer (photo by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)Marriage was still a distant prospect. Nettie went to Germany to study while Vance struggled to make a living from journalism in London. Back in Melbourne in November 1911 after her interlude of freedom, Nettie taught French and German at her former school, the Presbyterian Ladies College. Her father consented unenthusiastically to an engagement; he and her mother would have liked a son-in-law with steadier prospects, preferably in Melbourne. Vance’s lack of religious faith was against him too but, because Nettie had long since admitted that she never prayed, it couldn’t be made an issue. In the end it was a question of income. Vance had developed a useful network in London, and he told Nettie that poverty was easier to endure there than it would be in Australia.

Nettie and Vance had to wait until May 1914, when she joined him to marry in London. They would have preferred a civil ceremony but deferred to Nettie’s parents in choosing the Chelsea Chapel. They were both nearly thirty years old. Ahead of them were major careers in Australian literature, as creators and promoters. No one did more to encourage new writers and give them a sense of community that Australian writers, deferring to British publishers and readers, had never possessed.

These letters of love and longing are often touching, sometimes tediously drawn out. The philosophical, political, and literary currents of the day are thoughtfully discussed, but the letters seldom sparkle. Perhaps surprisingly, Nettie and Vance don’t seriously doubt the strength of their relationship during the long wait for marriage. And yet doubt was part of Nettie’s nature. Unsure of her creative powers, she remarked that the best thing about her poems was that they were too insignificant to worry about. Such diffidence sits oddly with the firmness with which she assessed the work of others. She put Vance’s career ahead of her own. In the years ahead, she would work to promote his novels as unobtrusively as she could, but her friends knew how she longed for him to get recognition.

Image of Vance Palmer (photo by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)Individually and as a couple, Vance and Nettie Palmer became powerful arbiters in the Australian literary world. Because Vance was primarily a novelist, his achievement as critic was less wide-ranging than Nettie’s. For a woman to succeed as Nettie did in making a living from literary journalism was without precedent in Australia. Today, anyone who traces the development of Australian literature from World War I to the 1950s will find Nettie’s fingerprints everywhere. Younger women writers found her a shrewd and generous mentor and friend.

Image of Vance Palmer (photo by John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland)Individually and as a couple, Vance and Nettie Palmer became powerful arbiters in the Australian literary world. Because Vance was primarily a novelist, his achievement as critic was less wide-ranging than Nettie’s. For a woman to succeed as Nettie did in making a living from literary journalism was without precedent in Australia. Today, anyone who traces the development of Australian literature from World War I to the 1950s will find Nettie’s fingerprints everywhere. Younger women writers found her a shrewd and generous mentor and friend.

Vance, too, was revered by the next generation, not so much for his novels, which were too often described as ‘well-made’, but for his fidelity to his ideals in Australian political life and literature. Deborah Jordan’s contribution to Palmer scholarship is especially welcome in taking us back to the uncertain beginnings of a remarkable partnership.

Comments powered by CComment