- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Ceridwen Spark reviews 'Traumata' by Meera Atkinson

- Custom Highlight Text:

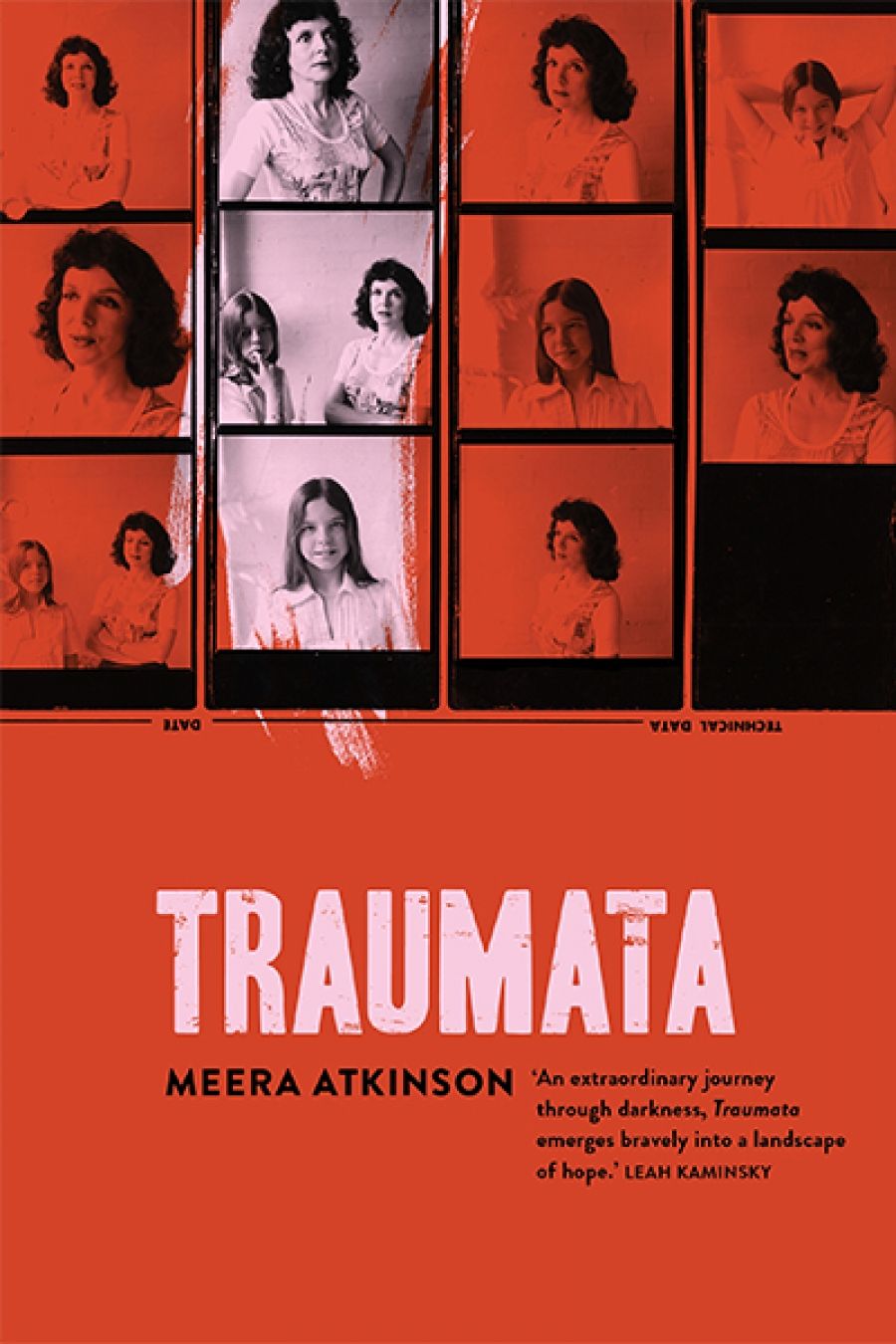

At first glance, Traumata seems to provide an exception to the rule not to judge a book by its cover. Featuring photos of the author’s mother, a woman in her forties, alongside photos of the young Atkinson on the precipice of adolescence, the cover portrays the filial relationship that is central in this memoir ...

- Book 1 Title: Traumata

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.95 pb, 285 pp, 9780702259890

The force that Atkinson identifies and seeks to trace is ‘patriarchy, with its endemic traumata’. While acknowledging that patriarchy ‘seems like an old-fashioned word’, Atkinson explains that she uses it because ‘there is no other word that gets at it’. Early on in the book, she declares her case, specifically why, in writing about patriarchy, she is focused first and foremost on her own experiences:

this is a book about patriarchy and its endemic traumata … I’m going to make the case that patriarchy is inherently traumatic, and that we might coin a new word – traumarchy – to denote the intersection of the two. Why, then, am I talking, in the next breath, of myself, my life? I have to speak from the inside out because patriarchy isn’t ‘out there’.

Traumata is an ambitious project. It covers much ground, including the author’s mother’s ‘addiction’ to destructive men, a close-up examination of the institutionalised bullying that manifests at school, and the meaning of female ‘beauty’ and its relation to patriarchy and trauma. It is honest, sometimes brutally so. Little escapes scrutiny: her mother’s ‘boob job’, done at the behest of her boorish partner, and Atkinson’s own sexual adventures and misadventures, are all described and analysed. While never easy reading, the book is provocative and poetic.

It is also courageous, for Atkinson surely endures the barrage of misogyny directed at women writers that seems now to be a norm. Perhaps it helps that she, unlike others with whom she is in conversation, including Clementine Ford and Amy Gray, would interpret such hatred as symptomatic of ‘traumarchy’. Because of the experiences she discusses – sexual abuse, addiction, living with violence – Atkinson makes a compelling case that trauma is everywhere. She writes, for instance, that ‘[n]ot all unfortunate events or even extreme sufferings are traumatic, but many are’, that ‘shit going down’ is ‘chronic’ and ‘common-place’, and that ‘no one gets out alive’.

With the exception of the chapter on friendship and the surprisingly more hopeful conclusion, the book is a palimpsest of suffering and survival. Atkinson stitches disparate moments together to demonstrate that she has been wounded. Declaring, ‘I’m writing through stigmata, but I don’t mean to suggest I’m a martyr’, she uses a matter-of-fact tone to describe being raped as a young woman, ‘fingered’ by her stepfather as a child, and her less clear recollections of interactions with the old man next door whom her mother says sexually assaulted Meera. We learn of other violations too: her mother’s betrayal of her to the violent stepfather with whom she was enthralled; her ‘pretty’ grandmother’s barbs about her weight, and her father’s absence, actual and emotional, from her life. While women are shown to perpetuate the wounds of patriarchy, they are also its victims, as Atkinson argues, are we all.

Meera AtkinsonAs a result of her openness, we learn much about Atkinson, and the shaky existence that is the lot of those who bear the wounds of what she refers to as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). Characterised by lingering fears and uncertainty that can rear up at any time and that underpin beliefs such as ‘The World Is Not Safe And You Will Be Annihilated Any Minute Now’, CPTSD is not yet recognised in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Described by Judith Lewis Herman as occurring in patients exposed to ‘prolonged repeated trauma’, it is a label Atkinson uses to describe her own condition.

Meera AtkinsonAs a result of her openness, we learn much about Atkinson, and the shaky existence that is the lot of those who bear the wounds of what she refers to as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). Characterised by lingering fears and uncertainty that can rear up at any time and that underpin beliefs such as ‘The World Is Not Safe And You Will Be Annihilated Any Minute Now’, CPTSD is not yet recognised in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Described by Judith Lewis Herman as occurring in patients exposed to ‘prolonged repeated trauma’, it is a label Atkinson uses to describe her own condition.

It is difficult to question either the logic of Atkinson’s argument, namely that patriarchy is the ‘big rape’ that damages and diminishes us all, or her own claim of having been damaged by it. Her case is further strengthened by her intellectual and literary chops. As well as being a creative writer, Atkinson is also an academic at Sydney University. Drawing throughout on neuroscience, feminist theory, and psychoanalysis to make her case, she enters ‘a tryst with the works of bygone philosophers’, including Nietzsche and Spinoza, to seek an answer to the question at the heart of the book: if traumata is so pervasive, what, if anything, can stand against it?

For some, her answer, that she weathers it, ‘in the rooms of therapists, in the community halls of support groups … on the phone to friends … patting a cat’ may be enough. For others, possibly those who have ‘endured a [less] privileged kind of traumata’ than that belonging to ‘white western womanhood’, it may not be. Either way, it is good that Traumata acknowledges that patriarchy wounds some more than others. Had it not done so, it would have succeeded as a memoir, but is unlikely to have been convincing as social analysis.

Comments powered by CComment