- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Dorothy Driver reviews 'Always Another Country: A Memoir of Exile and Home' by Sisonke Msimang

- Custom Highlight Text:

The name Sisonke Msimang may be familiar because of her reported claim in 2015 that Australia was ‘more racist’ than South Africa was during the apartheid era. What she in fact criticised were Australians’ failure to deal adequately with racial difference. Their recourse, she claimed, is to treat historical and present-day practices and manifestations of racism with ‘fake kindness’ rather than ‘honesty’, promoting a monoculturalism ...

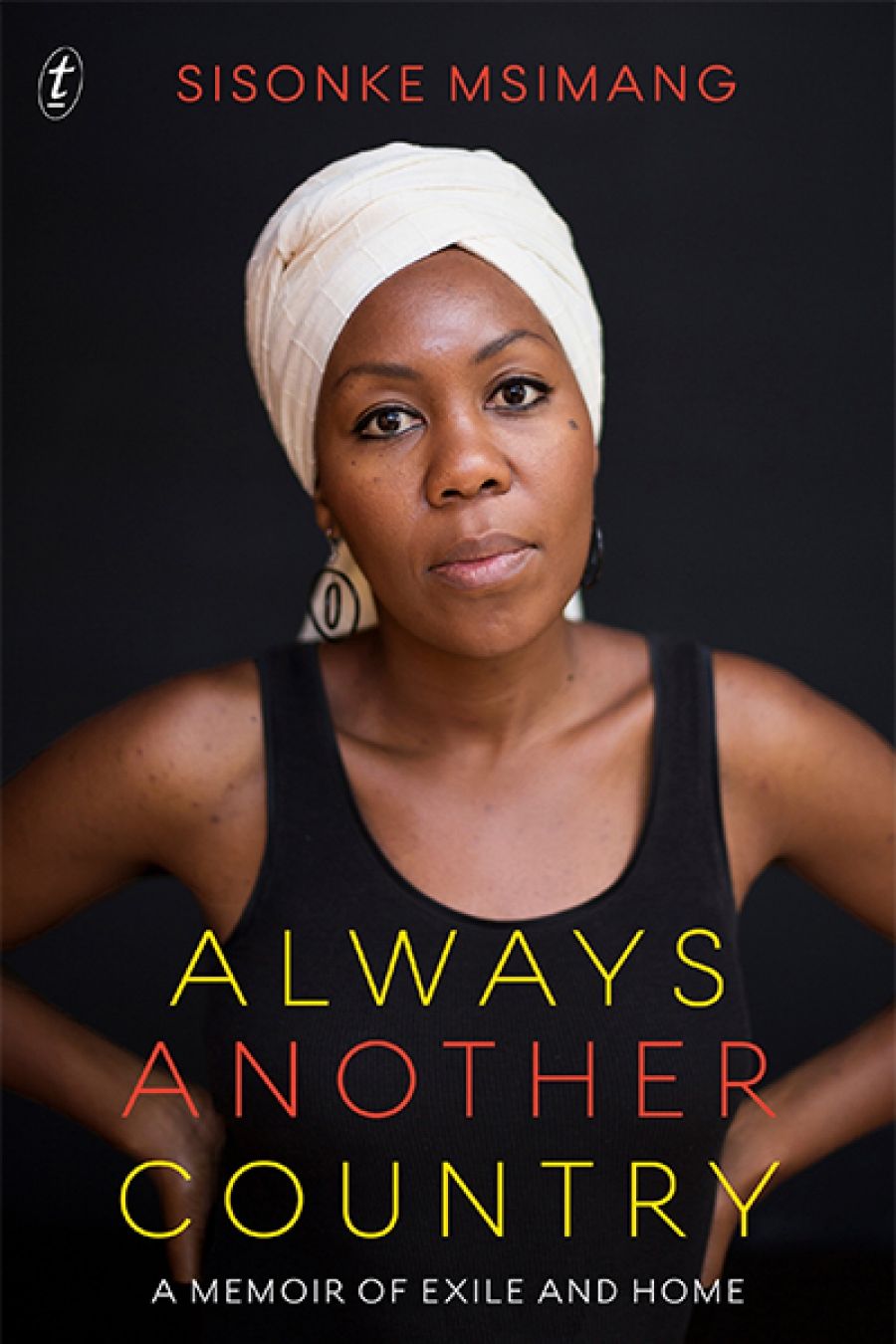

- Book 1 Title: Always Another Country

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir of Exile and Home

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 320 pp, 9781925603798

Australians are, nonetheless, ‘the nicest racists I have ever met’. Msimang should know: she has lived in Western Australia with her Australian husband and their young family for some years, while continuing her career as one of South Africa’s most interesting, well-informed, and outspoken journalists. She publishes across a wide range of media, including the New York Times, the Guardian, Al Jazeera, Newsweek, and the South African Daily Maverick, and is a contributing editor for the online journal Africa is a Country, which features some of the best writing about Africa and its diaspora.

Msimang’s memoir, Always Another Country, registers her relocation from South Africa to Australia, but its overall coverage is the series of moves she made, mostly with parents and siblings, from Zambia, where she was born, to Kenya, Canada, and the United States, usually on account of her father’s political activity (as a young man he had been recruited to the armed wing of the African National Congress). These countries, she suggests, have their own varieties of racism, but the memoir also traces the stealthy shifts of power via class and gender in their intersections with race.

Three events in particular mark Msimang’s early years, each involving physical violence, with the author placed as victim. Rather than offering a simple story of blame or possible complicity, however, she prefers to consider each event from its other side to offer intimate insight into the complex power differentials at work. Her account of an attempted rape when she was thirteen – marked by terrified assent (‘Is it nice?’; ‘I said yes so that I could live’) – portrays her attacker, the family gardener, as himself a victim, abandoned by Zambia’s ‘stunted revolution’. There is a similar account of the theft of her bicycle by a Luo street child, who is set upon by the lighter-skinned Kikuyu. The child is ‘desperate and poor and needlessly malnourished’, affording Msimang a glimpse of Kenya’s dire future.

The third event is different. Arriving just before the start of term at her liberal arts college in Minnesota, Msimang is harassed by a sinister young man who almost succeeds in entering her room (‘I ain’t gonna do a thing, pretty girl’). He mocks her for being ‘uppity’, albeit brown-skinned like him. Some passing college girls help shield her, but the threat will linger: ‘America is just like Kenya which is just like Canada which is just like Zambia which means there is nowhere in the world any of us can go to be safe.’ To be a girl, and black, may mean to be constantly on guard, fists at the ready, as her parents have taught her, but they instilled respectfulness, kindness, and self-inquiry as well. Msimang is a master of nuance and open-endedness: neither rage nor sentimentality can close off this event, and so, alongside the lingering threat, lies the memory of the eighteen-year-old’s polite apology to a pursuer she already knows will turn nasty: ‘I’m really sorry, I have to go.’

Sisonke Msimang (photograph by Nick White)Msimang’s narrative ability – angling stories to provide new perspectives, judgements, and meanings – enlivens the memoir as a whole. Even her arrangement of chapters bears thematic significance. The narrative pacing is by turns brisk or leisurely, and the figurative language, dialogue, and characterisation are superb. Persons familial, befriended, or merely encountered take on the kind of individuality we associate with fiction: her beloved great-aunt Lindiwe Mabuza (well-known to many South Africans as a political and cultural activist and writer); the amusing little sister who matures into Msimang’s wise adviser; the group of friends who chastise a Johannesburg café owner for her unkind treatment of a busking beggar; and the domestic helpers Msimang employs and cares for in her first days of marriage, who react to her as if she were their white ‘madam’. However self-conscious and acerbic her take on black self-righteousness and the contradictions of black class, she by no means blunts her critique of what she repeatedly calls the ‘heart of whiteness’ she confronts in South Africa, entering in the mid-1990s.

Sisonke Msimang (photograph by Nick White)Msimang’s narrative ability – angling stories to provide new perspectives, judgements, and meanings – enlivens the memoir as a whole. Even her arrangement of chapters bears thematic significance. The narrative pacing is by turns brisk or leisurely, and the figurative language, dialogue, and characterisation are superb. Persons familial, befriended, or merely encountered take on the kind of individuality we associate with fiction: her beloved great-aunt Lindiwe Mabuza (well-known to many South Africans as a political and cultural activist and writer); the amusing little sister who matures into Msimang’s wise adviser; the group of friends who chastise a Johannesburg café owner for her unkind treatment of a busking beggar; and the domestic helpers Msimang employs and cares for in her first days of marriage, who react to her as if she were their white ‘madam’. However self-conscious and acerbic her take on black self-righteousness and the contradictions of black class, she by no means blunts her critique of what she repeatedly calls the ‘heart of whiteness’ she confronts in South Africa, entering in the mid-1990s.

Msimang’s South African years are almost forestalled by her meeting, in her final year of college, a young man whose life she shares for a while. He is bipolar, paranoid, and insanely possessive. Although his delusions distress her, Msimang defends him as a product of US culture, but also finds in him a liberating unorthodoxy, for he eschews material possessions and refuses to get a job. It comes as a relief to her family and friends when this man’s strange allure is superseded by the tug of a newly liberated South Africa, and a relief to this reader as well, for the memoir at this point threatens to pall.

After Msimang’s parents return to South Africa, they energetically and optimistically engage in social and political reform. But Msimang’s years there are marked by a bleaker view. For her, the dream of a new South Africa fades, partly through the insidious perpetuation of white economic and social power coupled with white patronisation, partly through misgovernment. Betrayed by the political organisation that had once been a source of stability and honour for her and her extended family in their exile years, she quits the ANC. Her departure commences, she says, ‘when I pick up my pen’. In the act of writing she finds a new belonging, but it is necessarily coloured by distance and departure. ‘Home’, she writes, ‘will always be another country.’ Msimang’s life now involves shuttling between Australia and South Africa.

From her insider–outsider perspective, Msimang also gives an engaging and enlightening account of the years since 1994. Her memoir thus stands as a pinnacle in the newly burgeoning field of black South African feminist writing. Marked by self-assertion, self- reflection, and wit, along with a strong critique of the white economic strangle- hold and what Msimang calls ‘white saviour sanctimony’, this feminist writing generally – and Msimang’s memoir particularly – may help repair the fabric of a society profoundly damaged by colonisation and apartheid. Msimang fears the neoliberal greed of the ‘new and arrogant black’. But this is just one possible outcome her lively memoir invites us to imagine.

Comments powered by CComment