- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

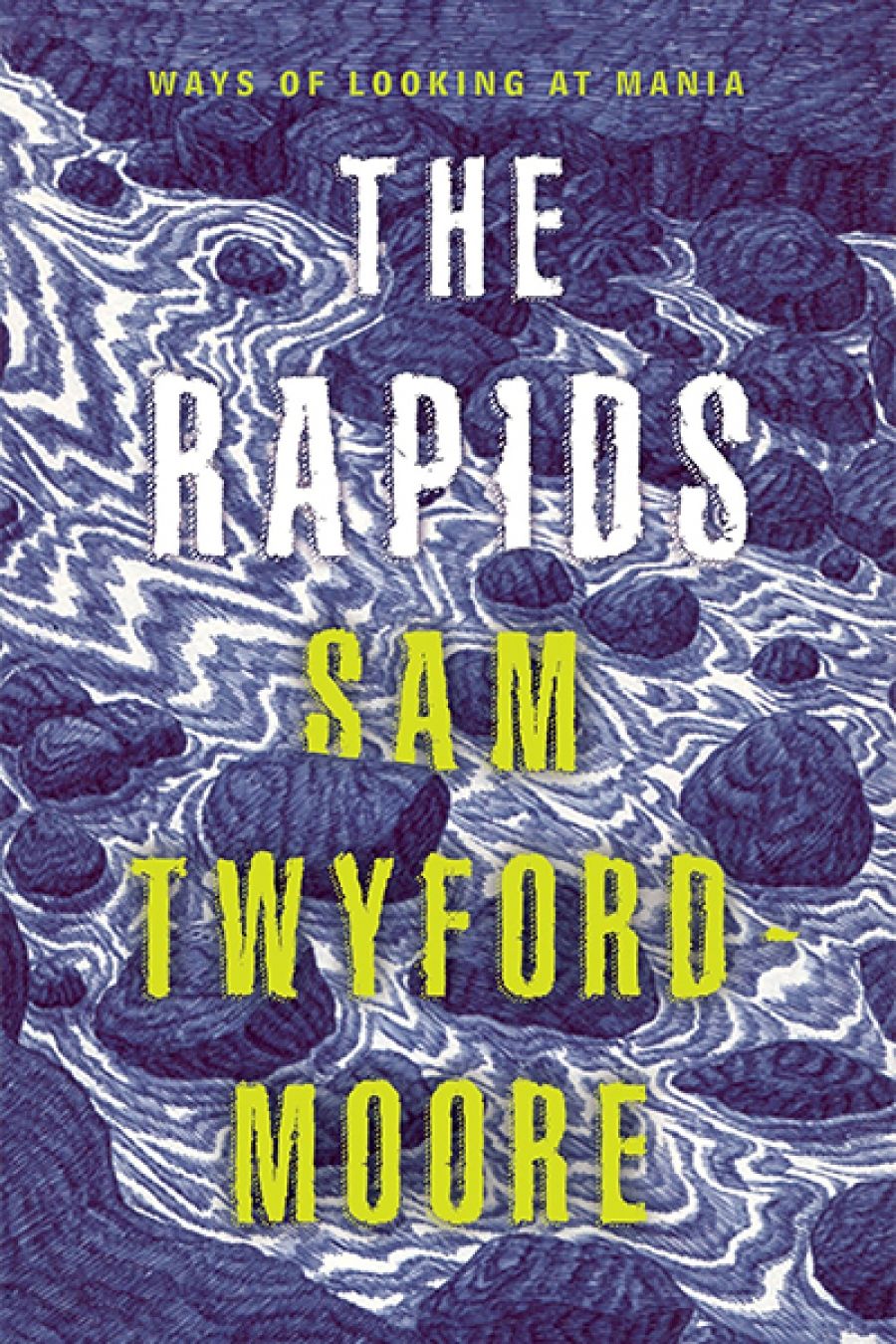

- Custom Article Title: Shannon Burns reviews 'The Rapids: Ways of looking at mania' by Sam Twyford-Moore

- Custom Highlight Text:

In The Rapids: Ways of looking at mania, Sam Twyford-Moore takes a personal, exploratory, and speculative approach to the subject of mania. Because the author has been significantly governed by manic episodes on several occasions (he was diagnosed with manic depression as he ‘came into adulthood’), The Rapids offers an insider’s perspective. It also considers some of the public and cultural manifestations of the illness ...

- Book 1 Title: The Rapids

- Book 1 Subtitle: Ways of looking at mania

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $32.99 pb, 280 pp, 9781742235653

The best parts of The Rapids are confessional and uncertain, and they follow a simple formula: This is what I did, thought and felt during a manic episode. I don’t know exactly what to make of it, but I don’t want to hide it either. These confessions are forthright and enlightening. ‘Mania,’ Twyford-Moore reminds us, ‘is a state of mood disturbance, typically associated with, and used to diagnose, what was once called manic-depression … which has been clinically replaced with Bipolar Affective Disorder.’ While the depressive side of the disorder typically attracts some public sympathy and understanding, the manic aspect – which can manifest as overconfidence (or grandiosity), excessive talking, a heightened sexual drive, and an overall loss of self-restraint – is little understood and rarely tolerated.

The Rapids begins with an account of activist–filmmaker Jason Russell’s public breakdown in 2012. He was recorded naked on a street corner in San Diego, ‘acting out of his mind’. Twyford-Moore calls this ‘the most public manic episode recorded’. Russell, he says, is now irredeemably ‘stained by stigma’. The implicit question is: why is this so, when other disabilities and misfortunes attract a more sensitive response?

The Rapids is a ‘collage-like’ exploration composed of short sections. This is partly the result of circumstance and partly derivative. Twyford-Moore began writing during his most recent manic episode, he says, when it was difficult to concentrate, but it is also ‘how my mind works most of the time’. He credits Wayne Koestenbaum’s Humiliation (2011) as a guiding influence, but the resemblance between the two books is superficial.

This is how Koestenbaum explains the formal qualities of Humiliation: ‘Some of my fugal juxtapositions are literal and logical, while others are figurative, meant merely to suggest the presence of undercurrents, sympathies, resonances shared between essentially unlike experiences.’ Humiliation features highly patterned flourishes, where connections run together artfully. Twyford-Moore doesn’t achieve this. Instead of developing ideas and building resonances between The Rapids’ various ‘ways of looking’, he tends to glance at an idea then abandon it, or to repeat it with shifts in emphasis or wording. For example, he writes that mania produced ‘a driving sense of strength and invincibility, and, along with this, a feeling of supreme healthiness … I miss my manias – a deeply dangerous, potentially deadly desire to go back.’ Just two pages later, we read: ‘My memories of my manias are largely fond, and intoxicating. I want to go back to them, back to that place of fun and play. But I can’t – or won’t – go back to the manias. They are, ultimately, dangerous ...’

At times, the need to identify a ‘shared way of thinking’ and discover ‘the river of similar feeling and same thought’ pushes The Rapids into absurd territories. Twyford-Moore exhibits unusually strong feelings for the public figures he writes about. This quirk culminates in the hero worship of Carrie Fisher. He says of her novels: ‘These are not perfect fictions, but, somehow, they equate to a perfect life.’ Somehow is doing a lot of work in that sentence. Then he asks: ‘If I say that “Carrie Fisher was my mental health icon” what do I mean? Part of it is the fact of saying it at all – the idea of there being such a thing as a mental health icon, or a mental health hero – feels like a relatively new concept ...’ Perhaps icon and hero are being used in an exaggerated or semi-ironic way, but it is discomfiting to see celebrities elevated to this level of personal and social significance. Dependence on or identification with icons or heroes appears more regressive than revolutionary, especially in a context where grandiosity is symptomatic.

Twyford-Moore is an uneven stylist. One of his sentences begins: ‘In his latest film, as I’m writing this, Phantom Thread, Paul Thomas Anderson crafts a film …’ He is not above describing a work of art as ‘a love letter to’ something or other, and it is hard to know what to make of sentiments like these: ‘Reading can be good, of course, for building character’ and ‘People base their morals on films’.

But artfulness and critical acumen aren’t essential qualities in this context. The Rapids’ true value is the part it plays in ‘fighting for [mania’s] legitimacy, in both medical and cultural terms’, since ‘It remains contested ground’. By this measure, the book is a success. I’m far more attuned to the signs, symptoms, and consequences of mania than I was before reading it.

Twyford-Moore asks: ‘Is there any other illness that has as a symptom, “makes you into a raging arsehole”?’ The lines that separate manic behaviour from brattish entitlement, criminality, or abuse aren’t always obvious. People gripped by mania are not fully themselves, yet they are more fully themselves; they are not entirely responsible for their behaviour, yet they are responsible. If we want to approach mania with maturity and compassion, we have to hold these contradictory truths in mind. Twyford-Moore effectively conveys the anguishing social and personal conflicts that mania can provoke, without offering crude solutions.

Comments powered by CComment