- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Custom Article Title: Andrea Goldsmith reviews 'Elements of Surprise: Our mental limits and the satisfactions of plot' by Vera Tobin

- Custom Highlight Text:

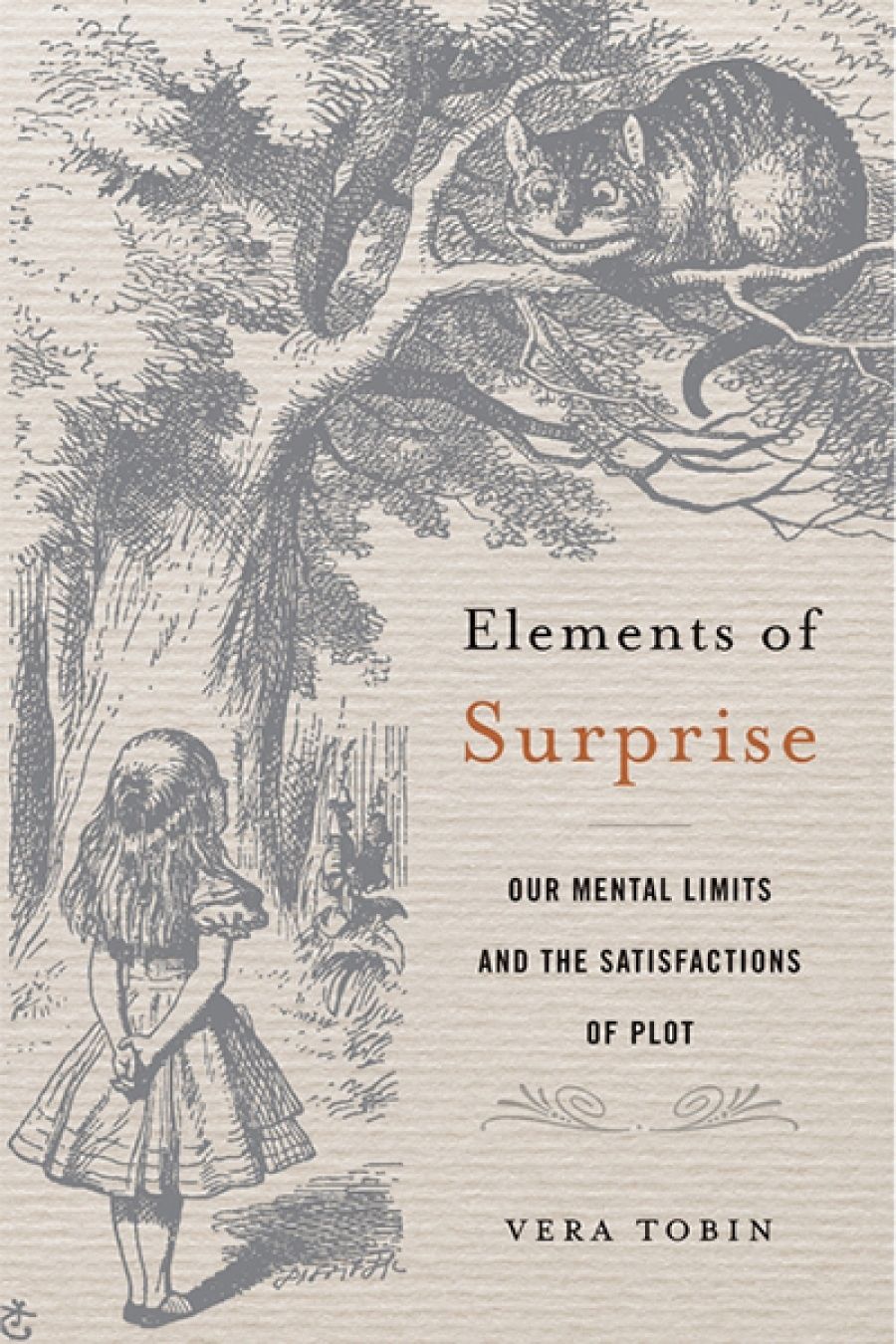

On the dust jacket of Elements of Surprise is the well-known picture by John Tenniel, illustrator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), depicting Alice gazing up at the grinning Cheshire Cat perched on a branch of a tree. I felt very much like Alice while reading Vera Tobin’s book, as if I had fallen into a world in which the rules, concepts, and vocabulary were completely alien to my own ...

- Book 1 Title: Elements of Surprise

- Book 1 Subtitle: Our mental limits and the satisfactions of plot

- Book 1 Biblio: Harvard University Press (Footprint), $66 hb, 332 pp, 9780674980204

Tobin does not totally ignore authorial techniques; she makes reference, for example, to the use of unreliable narrators and differing character points of view. But her emphasis throughout is that of the cognitive scientist, drawing on a wealth of experimental data stretching back to the 1980s. And while her main focus is on plot in novels (Ian McEwan’s Atonement and Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations are two examples) she also addresses surprise in films such as The Sixth Sense.

The primary concept Tobin draws on in her analysis of why people can be surprised when they read novels (or watch films) is ‘the curse of knowledge’. This refers to the common assumption that others will have the same knowledge and understanding as we do ourselves. The curse of knowledge leads to unconscious bias. After all, ‘the more information we have about something and the more experience we have with it, the harder it is to step outside that experience to appreciate the full implications of not having that privileged information’. By drawing on the curse of knowledge and how this cognitive tendency can be exploited, Tobin shifts the effects of surprise entirely on to reader cognition. In contrast, writers regard surprise and secrets as narrative material and in our control: how these are timed, the sorts of signposts and clues that are provided in the text, when to produce the moment of revelation and through which character, which characters will be in the know, and so on.

Authors are understandably vexed when they believe their books have been reviewed by someone ill equipped for the task. Might Tobin have the same complaint about this reviewer, one who has an interest in science but not particularly in cognitive science? I can’t evaluate the research she draws on, although I did find many of the experiments interesting. At times I was annoyed, at times I was frustrated, at times I shouted aloud – What about the writer? What about the effects of the reader’s imagination? What about the intimacy of reading? – but mostly I was caused to reflect in a way I would not if I had read a book about surprise in fiction written by another novelist. There were occasions when I found the language absurd (‘narratology’ and ‘narratological’, for example), and certain terms unnecessarily obscure: Tobin uses the terms ‘intradiegetic narrative’ and ‘extradiagetic narrative’ to describe a story within a story structure, or the framed story such as in Heart of Darkness or Wuthering Heights. Mostly, however, her approach was as Alice might have said, curiouser and curiouser, and I found myself in dialogue with the book in a way that I expect would not occur if I were reviewing a manual for writers or, indeed, if I were face-to-face with the author herself.

I am surprised that Tobin, as a cognitive scientist, ignores the dynamic of reading. It is such a captivating, intimate, exclusive process, one with the capacity to block out the surrounding real world and immerse the reader in a fabricated one. Surely this contributes to readerly susceptibility to surprise in fiction. And might there be something intrinsic to narrative itself that hooks into human cognition? After all, very young children respond to story. Indeed, storytelling has formed a part of human history since the cave dwellers, possibly earlier. And I question whether one can approach sleights of hand in film and in novels in the same way. While both employ techniques to manipulate reader/ viewer response (e.g., selective character point of view in print and camera angles in film), time is a crucial factor in surprise. In film the viewer goes at the director’s pace, but the reader of fiction sets her own pace, stopping here and there to mull, to wonder, to predict, to hope.

In the course of everyday life, we read books, watch television programs, and visit online sites that confirm our own views. Our friends in the real world and those we follow in the digital one are people like us who tend to hold the same views. I appreciated the opportunity offered by Vera Tobin to subject my own taken-for-granted interpretative framework to critical scrutiny. There seems to be far too little of it these days.

Comments powered by CComment