- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

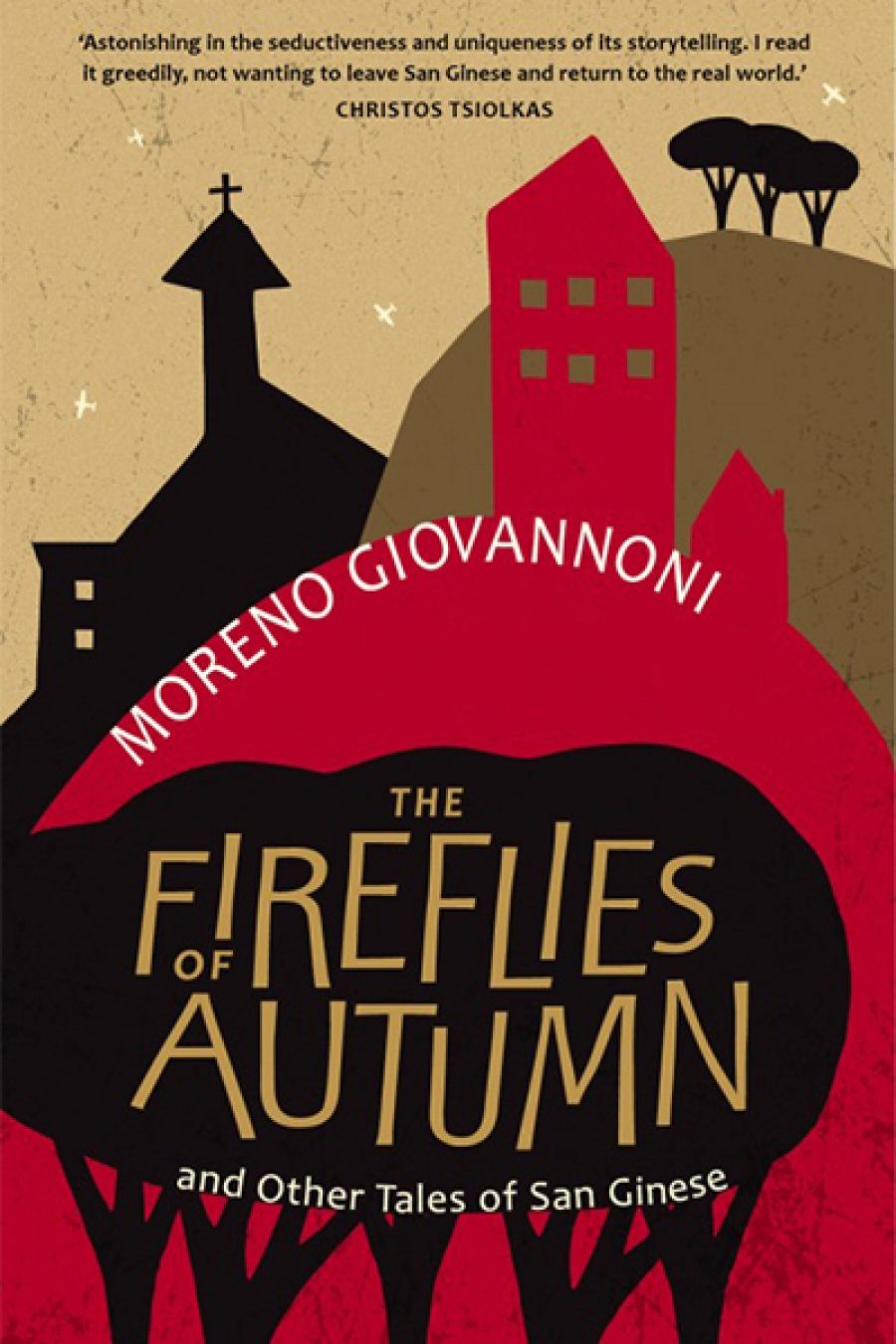

- Custom Article Title: Michael Brennan reviews 'The Fireflies of Autumn: And other tales of San Ginese' by Moreno Giovannoni

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Moreno Giovannoni’s collection of tales – populous and baggy, earthy and engrossing – offers not a history but the lifeblood, the living memory, of a small town in northern Italy called San Ginese, or more specifically a hamlet in its shadow called Villora. Villora is the point of departure and return for generations of Sanginesini, and the locus of the tales told ...

- Book 1 Title: The Fireflies of Autumn

- Book 1 Subtitle: And other tales of San Ginese

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.99 pb, 240 pp, 9781863959940

Soon after, Villora suffers just such a boundless oblivion in a chance cataclysm. This early tale, both of ends and origins, involves the saturation of Villora with perugino, a fermented brown liquid fertiliser made of human, cow, rabbit, chicken, and pig shit, which had so spread through the village as to recall something from Gabriel García Márquez, bringing with it a miasma of all-too-flammable methane, and set the scene for the arrival of Il Pomodoro, a short-lived character who lights the match that sets off the explosion that destroys the town where the events being recounted took place, or so we’re told. So far, so salty – and perhaps unreliable.

Or not. Memory, much as memoir, likes to play tricks to get at the truth. With the town taken care of, the tales flow, tangy and rich, as the relentless and relenting dramatis personae (we’re given a list of them in the back of the book for good measure) share their tales and mark their territory. It is a history of migrations through aspiration, love, and despair, machismo to pathos, arriving at a tentative homespun wisdom. Through oral culture and face-to-face encounters, the reader is witness to the fraying and recombination of San Ginese’s social fabric over a century of economic and political upheaval.

Owing more to Boccaccio than Sebald, the tales become a repository for the idioms of San Ginese. They encompass a multitude of characters making the best of their lives over generations, between the fascists and the invading armies of Germans and Americans, and the call of El Dorado, be it America, Argentina, or Australia. The tales tumble out loquaciously. Fortunes made abroad and, like love, lost at home or found again; exodus and migration; murder; revenge; betrayal – it’s got it all. We learn of Vitale in California and the Percheron, Iose Dal Porto the Flour-Eater, of Tista and the Mute, of Il Sasso, the Dinner of the Pig, of Mengale who planted nails and watched them grow, the priest Il Chioccino, and the killer Tommaso, of the dying agricultural economy, the twelve consequences of the war, and, of course, the titular fireflies of autumn. All of which is to barely scratch the surface of the compendium of local wit, gossip, and lore revelled in and unravelled. Amid all the journeying, poverty, and community remain the impetus and return of each migration. People leave San Ginese to find their fortune and return poorer for having found it. Even those returning from Australia are called Americans.

Moreno Giovannoni (photograph by David Patston)More than a unique and well-made story of migration and memory, which this is and which would be enough, these tales of San Ginese could be read as a tacit study of campanilismo and, in that respect, as a critique of the present. Campanilismo, rudely translated, might be read as ‘provincialism’ or ‘parochialism’, and might bring to mind the kind of narrow-mindedness of Australians wearing flag capes to a brawl at the beach. Not so. Campanilismo stems from campanile, Italian for the bell towers of churches or public buildings spread across the Italian landscape, and around which local towns, such as Villora, cluster and grow. It describes a loyalty to the town, or, perhaps better, commune, that preceded city states and the nation state of Italy, resonant with self-governing, smaller communities. Think Dunbar’s number and a rough and rustic idyll at odds with modernity. Think San Ginese. The ribald and fable-like comings and goings, regrets, and longings of four generations of San Ginese not only flesh out a history of generational migration, peopling the backstory of a boy born in San Ginese who grew up on a tobacco farm in Victoria, but subtly offer a plaint for the loss of campanilismo, a concept as difficult as the word to translate to contemporary Australia.

Moreno Giovannoni (photograph by David Patston)More than a unique and well-made story of migration and memory, which this is and which would be enough, these tales of San Ginese could be read as a tacit study of campanilismo and, in that respect, as a critique of the present. Campanilismo, rudely translated, might be read as ‘provincialism’ or ‘parochialism’, and might bring to mind the kind of narrow-mindedness of Australians wearing flag capes to a brawl at the beach. Not so. Campanilismo stems from campanile, Italian for the bell towers of churches or public buildings spread across the Italian landscape, and around which local towns, such as Villora, cluster and grow. It describes a loyalty to the town, or, perhaps better, commune, that preceded city states and the nation state of Italy, resonant with self-governing, smaller communities. Think Dunbar’s number and a rough and rustic idyll at odds with modernity. Think San Ginese. The ribald and fable-like comings and goings, regrets, and longings of four generations of San Ginese not only flesh out a history of generational migration, peopling the backstory of a boy born in San Ginese who grew up on a tobacco farm in Victoria, but subtly offer a plaint for the loss of campanilismo, a concept as difficult as the word to translate to contemporary Australia.

Late in the book, the Translator tells his own tale: returning as an adult to San Ginese and being confronted by the ‘prodigious’ failure of memory, the oblivion Ugo portended. The Translator recounts how the tales his mother told him on the journey to Australia left a ‘deep, slow-burning homesickness that brought an ache into his bones that never ceased and the source of which he did not comprehend until he was old’. Such homesickness is the heart of these tales, if not the community they suggest. Slow-burning surely, but worth the time spent in San Ginese.

Comments powered by CComment