- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Brenda Niall reviews 'Rosie: Scenes from a vanished life' by Rose Tremain

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Write about what you don’t know,’ British novelist Rose Tremain advised young authors. That has been her own strategy during a long and star-studded career. It is quite a stretch from the court of England’s Charles II in Restoration (1989), or that of Christian IV of Denmark in ...

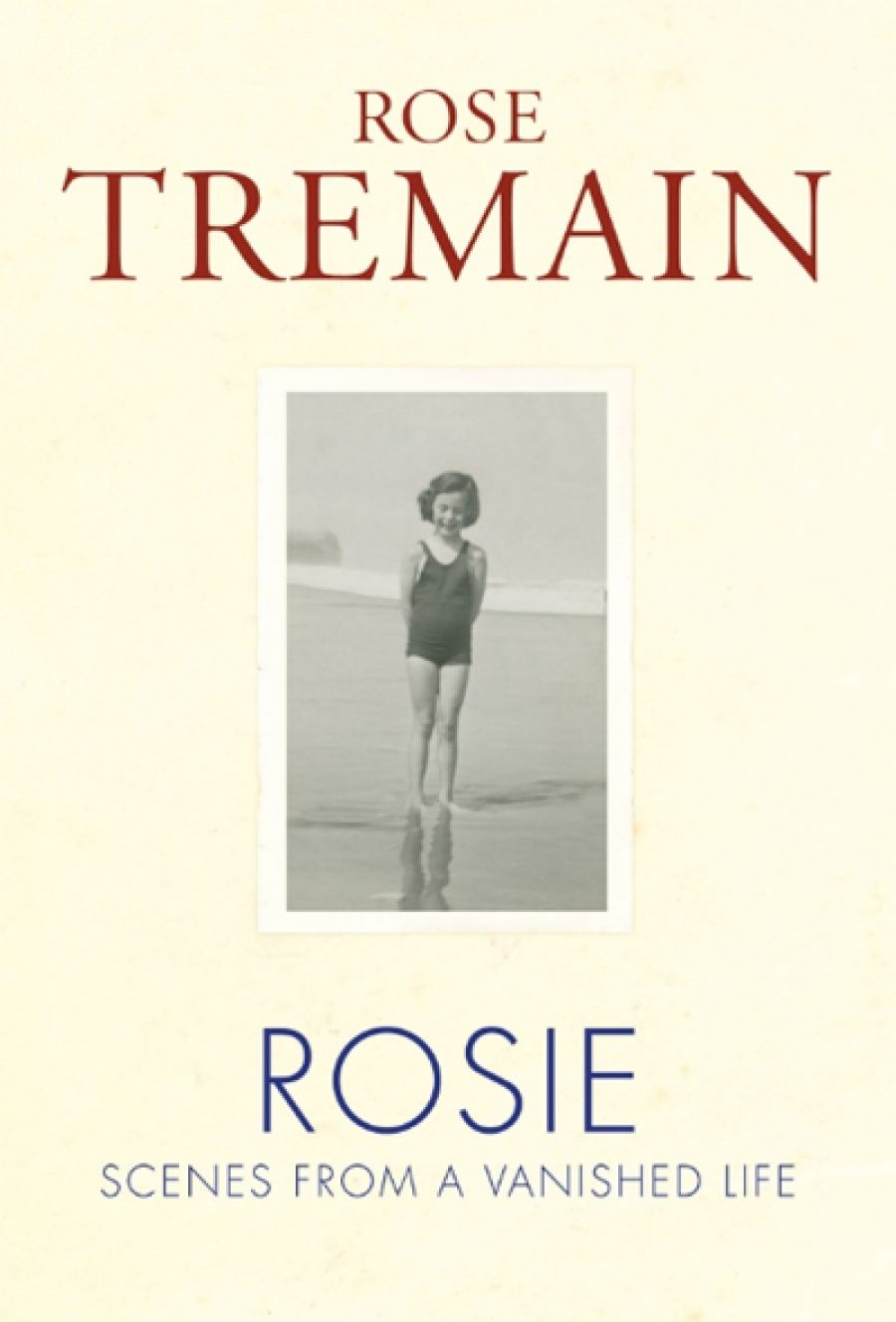

- Book 1 Title: Rosie

- Book 1 Subtitle: Scenes from a vanished life

- Book 1 Biblio: Chatto & Windus, $32.99 hb, 210 pp, 9781784742270

Tremain’s memoir of childhood raises expectations. By comparison, her contemporaries Ian McEwan and Julian Barnes are almost stay-at-homes, digging deeper into the English culture that they know. What has made Tremain such a relentless traveller in alien times and places?

Rosie: Scenes from a vanished life is embedded in ‘Englishness’. The title suggests a wistful, backward look at a world, once intimately known, now lost. Once more, Tremain shows her capacity to surprise. Although the book begins with an ecstatic return to the lost paradise of her grandparents’ house and estate in Hampshire, it becomes an exploration of an unhappy family. It asks King Lear’s question: ‘Is there any cause in nature that makes these hard hearts?’ The memoir is about the lack of maternal love in two generations, and Tremain’s attempt to understand and forgive.

There are echoes here of Tremain’s finest novel, The Gustav Sonata (2016), in which a ruinous mother–son relationship plays out in wartime Switzerland. Perhaps, too, the bleak marriage in The Colour, or the mutual loss felt by father and daughter in The Road Home carry some emotional freight from Tremain’s early experience.

Rose Tremain was born Rosemary (Rosie) Thomson, the younger of the two daughters of a disgruntled failed playwright, Keith Thomson, and his emotionally brittle wife, Jane. This mismatched pair had a house in upper-class Chelsea in the 1940s and sent their daughters to a private day school near home. As far as Tremain can remember, it was a house without love except for the saving grace of a nanny, Nan, whom she remembers with gratitude as her rescuer. She wished that Nan, ‘the kindest person I’ve ever known’, was her mother. She shared a bedroom with Nan for the first ten years of her life.

Postwar Chelsea didn’t have the fashionable glitter it attained in the 1960s. In Tremain’s memory, it was pleasant but ordinary. Even in the early 1950s, food rationing hadn’t ended; she remembers dull meals of Spam, tinned ravioli, Kraft cheese slices, and lots of bread and jam. Holidays with Jane’s parents in Hampshire were an escape into freedom. Not that the grandparents were loving, but the place itself, Tremain says, was magical in its natural beauty and outdoor freedom. A good cook, and abundant produce grown on the estate, meant lavish meals. Instead of Spam and Kraft cheese in the nursery, the children dined with their grandparents on ‘roast grouse, honey-baked ham, rhubarb syllabubs, treacle puddings, apple pies and cream’. Best of all was the regime of more or less benign neglect. So long as they turned up to meals looking tidy, no one minded what Jo and Rosie did. They climbed trees, rode bicycles through puddles, enjoying the muddy splashing, fed the hens, collected eggs, learned to drive a pony cart.

The first in a series of losses was the death of their grandmother, soon followed by that of their grandfather. The Hampshire paradise vanished. The next to disappear was their father. After some unconvincing stories about his being away somewhere writing a play, Jo and Rosie were told the truth. ‘He had gone away for ever; he didn’t love us anymore.’ The girls heard their mother crying in the night, but she didn’t share her grief. She sent the two of them to boarding school. That meant losing Nan, their one source of love and stability.

Their boarding school had the weird blend of grand surroundings and interior squalor that English upper-class parents thought good for children. Badly fed, allowed only two baths a week, their underwear seldom laundered, ‘we stank like polecats’. While Rosie and Jo were still lost in homesick misery, ‘the grown-ups of the family were playing musical beds’. After two divorces, a new family grouping emerged when Jane married their father’s cousin, who had a son and daughter. Life in London ended abruptly. Nan, who had reappeared briefly, vanished again, an unconsidered victim of the new deal.

The later scenes of Tremain’s memoir continue the theme of loss. Rosie began to enjoy school where a good teacher of literature roused hopes of Oxford. This was not allowed; her mother didn’t want a ‘bluestocking daughter’. Rosie was sent to finishing school in Switzerland, to learn how to be an upper-class wife, or, failing that, a secretary to some powerful man.

This chronicle of losses, in which good things are snatched away without apparent reason, takes Tremain to her nineteenth year. That’s when her resentful compliance ended. She refused to fit into her mother’s pattern, discharged herself from language school in Paris, enrolled at the Sorbonne, and began a liberated student life. Later, she rejected the hated name of ‘Rosie’ and insisted on ‘Rose’.

Rose TremainAll through her narrative of childhood, Tremain searches for the woman whom she refers to as Jane, not ‘my mother’. Pondering the family history, she begins to understand that Jane, too, was emotionally starved. Jane had two brilliant, beloved brothers: one died suddenly at boarding school from a ruptured appendix; the other was killed in the last month of World War II. Jane, the survivor, meant nothing to her parents, who shut her out of their grief.

Rose TremainAll through her narrative of childhood, Tremain searches for the woman whom she refers to as Jane, not ‘my mother’. Pondering the family history, she begins to understand that Jane, too, was emotionally starved. Jane had two brilliant, beloved brothers: one died suddenly at boarding school from a ruptured appendix; the other was killed in the last month of World War II. Jane, the survivor, meant nothing to her parents, who shut her out of their grief.

Tremain believes that, in coming to understand a destructive sequence of maternal failures, she herself has been able to break it. Her relationship with her own daughter is happy, and she has two grandchildren whom she loves. For this restoration of the natural order, she gives full credit to Nan, the one constant protective presence in her early life, her only teacher of love.

There is another story which perhaps Tremain will one day tell. This memoir ends before she began to write, before she married (unhappily, twice), and before biographer Richard Holmes became her life’s companion. The author focuses on the child who struggled to make sense of a bewildering world. The gap between knowledge and understanding is subtly measured. For its emotional range and its deft management of a limited point of view, the memoir recalls Henry James’s What Maisie Knew. ‘What Rosie Knew’ would have been an apt title.

Comments powered by CComment