- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

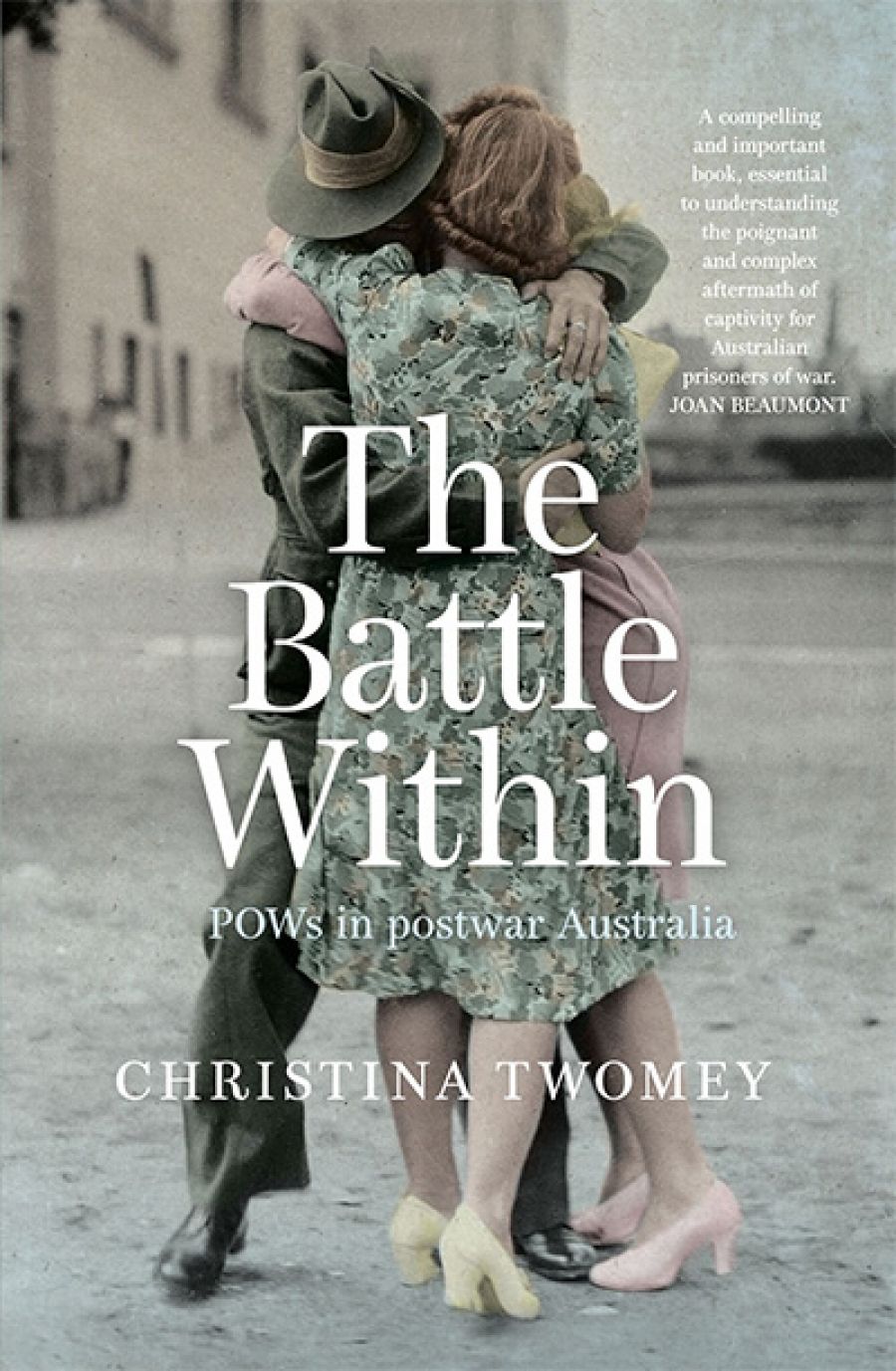

- Custom Article Title: Carolyn Holbrook reviews 'The Battle Within: POWs in postwar Australia' by Christina Twomey

- Custom Highlight Text:

The director of the Australian War Memorial, Brendan Nelson, recently announced plans for a $500 million underground expansion of the memorial. In justifying the expenditure, Nelson claimed that commemoration ‘is an extremely important part of the therapeutic milieu’ for returning soldiers; ‘I’ve particularly learned from the ...

- Book 1 Title: The Battle Within

- Book 1 Subtitle: POWs in postwar Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 320 pp, 9781742235684

It is tempting to see the current veneration of POWs as running along clear rails, from the past to the present. This book suggests that the sidings were many, that the tracks were buckled and warped, and that the burden of this difficult journey fell most heavily on the people with the least social, cultural and economic resources to carry it.

The Battle Within is both an eloquently written, page-turning story about suffering and survival, and a compelling analysis of the changing nature of Australian society in the decades after World War II. In tracing the plight of the returned POWs, Twomey also documents the transformation of the Anzac legend, from a mythology grounded in an ideal of masculinity that prized military prowess and stoicism, to one that allowed for emotional vulnerability and physical frailty. The Battle Within shows how this transformation was made possible by the embrace of ‘trauma culture’ from the 1980s.

More than 30,000 Australians were imprisoned during World War II; nearly three-quarters of those by the Japanese. The death rate among prisoners of Germany and Italy was three per cent. It was thirty-six per cent among those captured by the Japanese; a rate second only to those in Bomber Command who flew air raids over Europe. Whatever joy the emaciated, diseased prisoners of Japan felt upon liberation was soon tempered by their reception in Australia.

Derision of POWs trickled down from the top of the army and the repatriation bureaucracy into the community at large. The head of the army, Thomas Blamey, wrote to his minister, Frank Forde, that ‘surrender … in preference to death is dishonourable’. Thus, any tendency to ‘extol’ the prisoners ‘or give them privileges greater than soldiers who have not surrendered’ must be resisted, lest their behaviour be seen to be condoned. The Repatriation Department was adamant that POWs receive not special treatment for the same reason. Its policy of ‘complete avoidance of any publicity concerning them’ only compounded the resentment and isolation of the former POWs.

Messages about failed masculinity were reinforced by the leaders of the returned POW community, men whose class and rank marked them apart from the bulk of the returned prisoners. Ted Fisher and Albert Coates, both of whom served as doctors in the camps, would not countenance the existence of ‘barbed wire disease’ – the notion that captivity and mistreatment might cause specific forms of psychological illness. Fisher was particularly adamant. He had no truck with ‘sob stuff’, and insisted that the majority of neurosis cases could be explained by gastrointestinal infection. Fisher was cross about the fact that some men suffering from anxiety ‘got to the psychiatrist before stool examination had been reported’.

The POWs themselves were deeply ambivalent about an experience that confounded entrenched principles of gender behaviour. How could they reconcile their nightmares, impotence, and social anxiety with cultural mores that told them their suffering was the result of inherent flaws and moral weakness? Self-hatred and shame sat alongside anger and bitterness about their rejection by the military establishment.

The voices of these ordinary men come to us through the records of the Prisoners of War Trust Fund. The organisation was set up by the Menzies government after the veterans’ campaign for subsistence pay compensation was rejected by an independent panel. It is through their poignant and sometimes desperate appeals for financial assistance that we learn about the difficulties many returned prisoners faced in maintaining intimate relationships, steady employment, and peace of mind.

Australian POWs in Changi Prison, 1944 (photograph by Jack Warner, AWM 043131)

Australian POWs in Changi Prison, 1944 (photograph by Jack Warner, AWM 043131)

By the 1980s, large-scale studies of the health of returned POWs began to show what had long been understood by those who were prepared to listen. Former POWs suffered from psychiatric disorders, most commonly anxiety and depression, at nearly twice the rate of other ex-service personnel. The newfound ability of military and bureaucratic institutions to acknowledge the psychological suffering of POWs can be attributed to a change in the zeitgeist. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was listed in the 1980 edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Crucially, PTSD was triggered by external trauma rather than the innate fragility of those who suffered.

Anzac Legend 1.0, with its emphasis on Australians’ martial prowess, had no place for the martially denuded prisoners of war. Increasingly, the imperial and racial connotations of the traditional Anzac myth were spurned by a society that was shedding its British identity and navigating economically towards Asia. It was only after Anzac divested itself of its imperial, martial, and racial connotations and re-emerged in the 1980s as a mythology of mateship, sacrifice, and suffering, that it could be begin its extraordinary revival. A notable new feature of Anzac 2.0 was the prisoner of war experience, with Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop, a former medical officer on the Thai– Burma Railway and campaigner for POW rights, as the POW poster boy.

In 2015, Christina Twomey gave a talk about the struggle POWs faced to have their plight recognised at a conference that included contemporary veterans and mental health practitioners. After she finished her talk, a veteran of Somalia and East Timor turned to Twomey and said: ‘Nothing’s really changed.’ Twomey’s book documents the failure of the state and society more generally to look after the POWs of World War II. Furthermore, it suggests that the $500 million Brendan Nelson wants to spend on displaying Chinook helicopters and F/A18 hornets in the Australian War Memorial would be better directed to support services that help contemporary veterans as they fight the battle within.

Comments powered by CComment