- Free Article: Yes

- Contents Category: Memoir

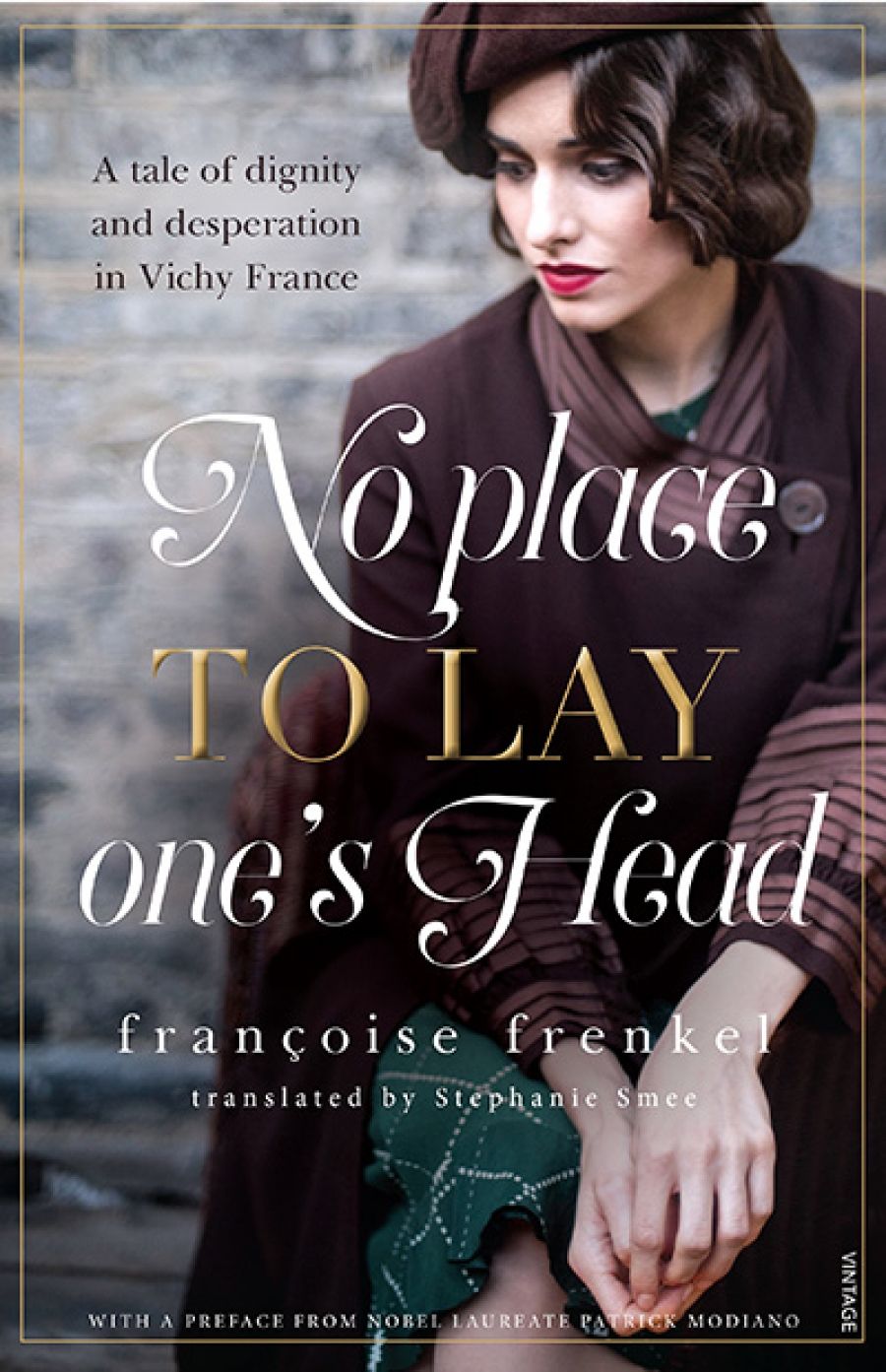

- Custom Article Title: Avril Alba reviews 'No Place to Lay One’s Head' by Françoise Frenkel, translated by Stephanie Smee

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When German forces invaded France on 10 May 1940, the French signed an armistice that facilitated limited French sovereignty in the south, the section of the country not yet overrun by German troops. On 10 July 1940 the French Parliament elected a new, collaborationist regime under former general Philippe Pétain ...

- Book 1 Title: No Place to Lay One’s Head

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $34.99 pp, 299 pp, 9780143784111

Memoirs such as Frenkel’s have become a staple of Holocaust literature. Barely a year goes by without the publication of many such stories. The question then becomes the point of difference. In No Place to Lay One’s Head, the difference lies in its immediacy. Frenkel wrote this absorbing memoir almost immediately after her escape to Switzerland in 1943, when the terrifying and uncertain nature of her ordeal had not been coloured by the passage of time. Too often, distance sanitises such recollections, as the teller understandably views her experience from the vantage point of a life recovered and reconstituted, rather than one so nearly destroyed.

As a result of this proximity, descriptors such as ‘occupation’ and ‘persecution’ are not abstract notions, but rather translate into hundreds of discrete decisions as to how best to anticipate and respond to the effects of each new discriminatory measure. For example, when French nationals and non-nationals of Jewish ‘racial’ origin were compelled to have a ‘J’ for Juif stamped on their papers, Frenkel, along with thousands of other Jewish non-nationals, had to decide whether to follow the order and risk deportation or to go yet again into hiding, leaving herself at the mercy of strangers.

Unflinching in her honesty and refreshingly free of sentimentality, Frenkel recounts the everyday heroism of those who put their own and their family’s lives at risk to help, alongside the acts of complicity, fear, and greed from those who would ultimately betray her. Most poignant are the stories of neither the heroic nor the malevolent, but those of individuals whose ‘ordinariness’ resonates with our own as we ponder how we too, in such extreme and dangerous circumstances, might have acted.

It is her ability to convey the ‘complexity of the ordinary’ that is the most significant contribution of Frenkel’s memoir. Her forensic yet never dispassionate powers of observation, so well conveyed in Stephanie Smee’s spare and elegant translation, allow this complexity to be brought to bear. She does not relieve her readers of history’s burdens but rather presents them with its deeply contradictory and perhaps ultimately unresolvable difficulties. Keenly aware that French is Frenkel’s second language, yet equally cognisant of her fluency in her chosen tongue, Smee’s translation moves seamlessly from the author’s lyrical and descriptive passages (the voice usually deployed when describing her physical surrounds and the characters she encounters), to commentary which borders on a more direct style of reportage (for example, practical matters such as obtaining provisions while under the occupation). Throughout these passages, Frenkel does not exculpate but nor does she condemn. In her judicious retellings she renders intelligible, some seventy years on, the precariousness of life in occupied France.

It is often a mistake to assume that historical narratives transcend their particular time and place, yet to my mind it is impossible to read Frenkel’s memoir without feeling its contemporary resonance; to hear the voices of the hundreds of thousands of Frenkels who today flee over different borders, for different reasons, with the same urgency and confronting the same indifference that Frenkel’s memoir hauntingly conveys. Recognising that these struggles have yet again become commonplace is perhaps the most poignant aspect of reading Frenkel’s memoir, as well as the most important reason that its translation and republication should be undertaken today.

Comments powered by CComment