- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Seumas Spark reviews 'Australia’s Northern Shield? Papua New Guinea and the defence of Australia since 1880' by Bruce Hunt

- Custom Highlight Text:

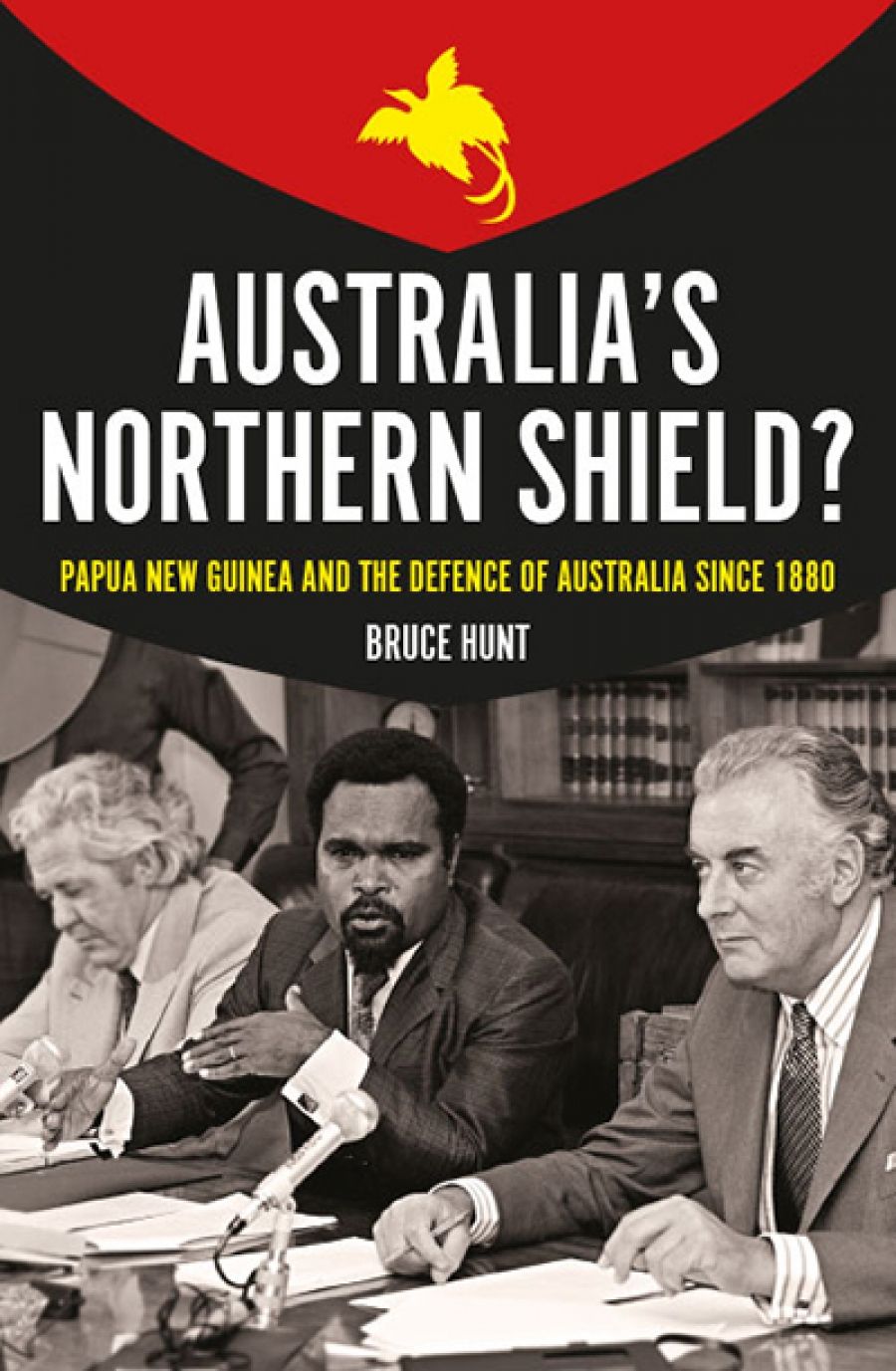

The subtitle of this book is Papua New Guinea and the Defence of Australia since 1880. Michael Somare, first prime minister of Papua New Guinea (PNG), is at the centre of the cover photograph, and the cover design uses red, yellow, and black, the colours of the PNG flag. Yet for much of this book PNG is at the periphery of ...

- Book 1 Title: Australia’s Northern Shield?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Papua New Guinea and the defence of Australia since 1880

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 400 pp, 9781925495409

Australia assumed control of British New Guinea in 1906 and German New Guinea in 1921. In the early twentieth century, Commonwealth governments saw the eastern half of the island of New Guinea as a shield to defend Australia from Japan and hostile European colonial powers. The idea of New Guinea as a shield persisted. During the second prime ministership of Robert Menzies, from 1949 to 1966, the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, as it was known at this time, was seen as a barrier against the spread of communism and Indonesian influence. The Territory was so important to Australian interests that Menzies and his ministers were prepared to commit forces to its defence.

In writing this book, Hunt had access to records of meetings of the federal Cabinet from 1950 to the mid-1970s. These records, known as Cabinet notebooks, have only recently become available, and Hunt, rightly, makes much of them. Of the thirteen chapters in the book, ten cover the period 1949 to 1977. Unearthing new sources is one of the joys of historical research, and the easy part of the historian’s task. The hard part is translating discoveries in the archives into engaging prose that blends narrative detail and analysis in the right measure. This challenge Hunt does not always master. Some of the writing is so detailed that it can be difficult to distinguish how a point made on one page differs from a point made elsewhere. Hunt completed a doctoral thesis on the subject of this book, and parts of Australia’s Northern Shield? carry the stamp of something written with academic examiners in mind.

If detail is a weakness of this book, it is also a strength. In his forensic study of the Cabinet notebooks, Hunt has uncovered gems of information. Menzies thought President Nasser of Egypt was ‘full of himself’ and ‘looking for fresh worlds to conquer’, and he saw President Sukarno of Indonesia as a leader in the same mould: a troublesome nationalist upsetting the order established by the liberal democracies of the West. John Gorton, prime minister from 1968 to 1971, worried about secessionist movements in the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. In Cabinet in 1969 he drew a parallel with the separation of Biafra from Nigeria. Should Australia intervene in the event of civil war in the Territory? The answers offered by members of Gorton’s Cabinet, including Malcolm Fraser, will interest historians of Bougainville in particular.

Most interesting of all is what the Cabinet notebooks reveal about John McEwen, long-serving conservative MP and, from 1958, leader of the Country Party and deputy prime minister. McEwen is best known for his support of Australian primary producers, whose cause he championed as the minister with responsibilities for commerce and trade. Now we know that he was also a perceptive judge of international affairs. In Cabinet he spoke for restraint and diplomacy in Australian–Indonesian relations, arguing that good relationships with Indonesia and other Asian countries were vital if Australia’s future were to be stable and prosperous. Some of his interventions anticipate what Gough Whitlam and Paul Keating would say in later years. As political leaders who supported closer ties between Australia and Asia, McEwen, Whitlam, and Keating make an unlikely trio.

Malcolm Fraser with the former Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea Julius Chan, Melbourne, 1981 (National Library of Australia)

Malcolm Fraser with the former Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea Julius Chan, Melbourne, 1981 (National Library of Australia)

There are various minor errors in this book. For instance, we are told that 2,165 Australians were killed in the Papuan campaign in World War II, and later that the same number died in fighting at Kokoda. The historian Peter Stanley is said to work at the National Museum of Australia, an institution he left several years ago. The name of the British politician Denis Healey is misspelt. All the errors are inconsequential, and of the sort that every author makes in writing thousands of words, but in this book too many have slipped through the drafting and editing stages. Stern editing would have produced a stronger book, and a shorter one.

In the last chapter is a brief summary of the Australia–PNG defence relationship since 1977. Hunt might have offered a comment on a wonderful irony: the deepening economic and political ties between PNG and China. More than fifty years after the end of the Menzies era and fears of reds under beds, a communist power exerts ever more influence in Australia’s former colony. I wonder what ‘Black Jack’ McEwen, sage of Australian–Asian relations, would have made of that.

Comments powered by CComment