- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Dance

- Custom Article Title: Lee Christofis reviews 'Fifty: Half a century of Australian dance theatre' by Maggie Tonkin

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australian Dance Theatre, the nation’s longest continuing modern dance company, was born in 1965, during the so-called Dunstan renaissance of Adelaide. Elizabeth Cameron Dalman, a dancer and teacher influenced by five transformative years in Europe, and Leslie White, a dancer and teacher trained at the Royal Ballet School ...

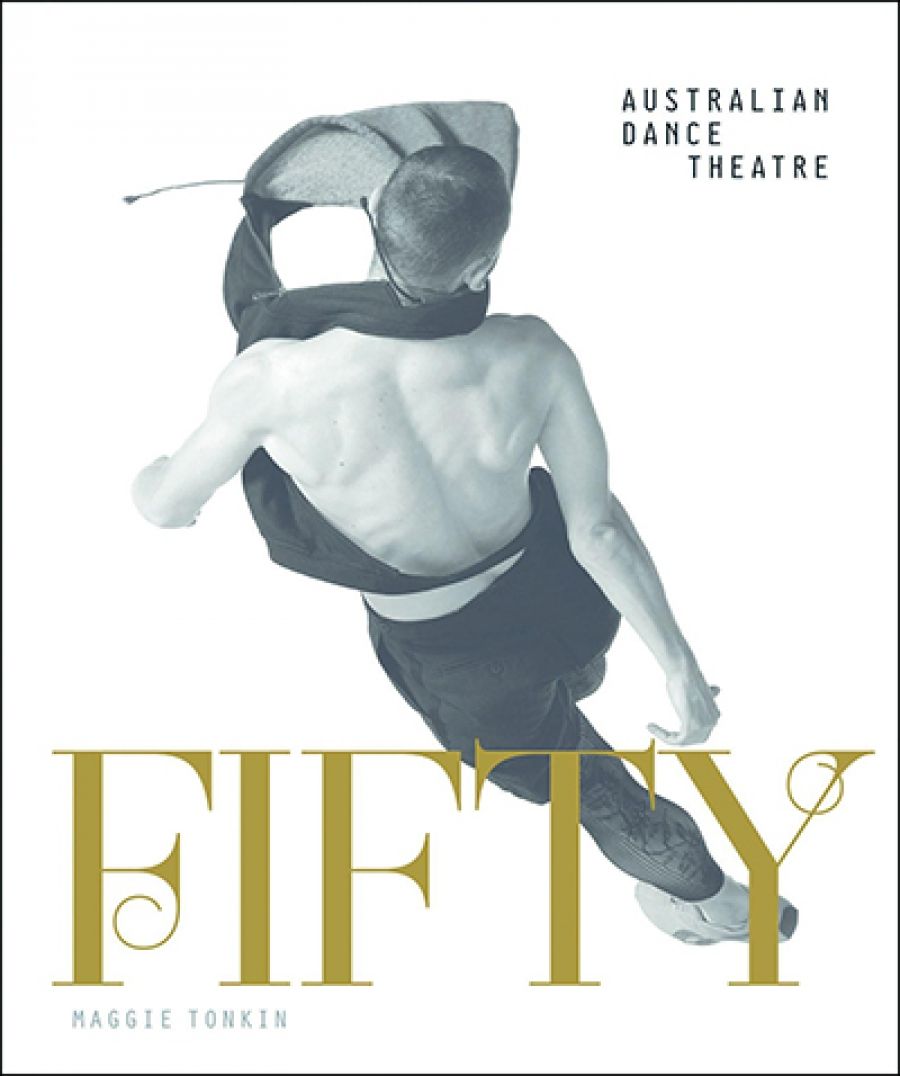

- Book 1 Title: Fifty

- Book 1 Subtitle: Half a century of Australian dance theatre

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $75 hb, 180 pp, 9781743054581

These pressures were a reminder that ADT endured considerable turmoil while it achieved many artistic triumphs at home and abroad. Not least was the sudden termination of four artistic directors in twenty-five years, resembling a tradition, as Tonkin writes in Fifty: Half a century of Australian dance theatre. But ultimately, it is the artists and their achievements that are celebrated here, and Tonkin does so with dignity and humility. Her many interviews makes Fifty an intimate insider’s story, even though the boards’ reflections on past actions do not feature in it, leaving many questions unanswered. One can’t help but wonder what else Tonkin might have explored had Cameron Dalman not written the book’s opening chapter. Luckily, confidentiality conditions do not prevent the large clusters of images from illustrating the company’s development in this most colourful publication.

Initially, Cameron Dalman’s mother, Lady Wilson, was a good committee organiser, which helped support the fledging company’s activities. Small grants emerged, and precious Australia Council money began in 1969. Cameron Dalman’s initial vision was fed by stunning landscapes, Aboriginal rock art, and our complex post-colonial history. Later, the charismatic Columbian-American choreographer Eleo Pomare, an angry James Baldwin of black dance, would inspire her company with dances fuelled by social justice and protests against racism. By 1971, ADT had successfully toured all the capital cities; over the next two years it performed before 58,000 people. By 1975 it had given 173 performances and run a successful education program. But a growing lack of confidence among the board provoked them to import choreographer Jaap Flier from Nederlands Dans Theater to enhance the repertoire; little change resulted. On 11 October 1975, Cameron Dalman and her dancers returned to their dressing rooms after their last show at the Seymour Centre, Sydney, to find dismissal letters from the board. The urge to rebel was quelled by ‘good advice’ and the company folded. Shock and bitterness would last for years, especially as there was little financial reward from that period. Cameron Dalman suggests that the combined decades’ efforts by everyone in the company would be worth around $15,000,000 today.

Jonathan Taylor earned his first money tap dancing with his dad in Manchester, England, and later in television, musicals and London’s prestigious Ballet Rambert. After negotiations ADT became a repertory company and built a superb leadership team with Rambert colleagues – American Joe Scoglio, English choreographer and ballet mistress Julie Blaikie, and Taylor’s Dutch wife Ariette, who would run another lucrative education program, Mummy’s Little Darlings. Dancers and choreographers who joined Taylor’s team profited from their combined dance and theatre craft, and challenging works by Christopher Bruce and Norman Morrice in England, and a commissioned piece American modern master, Glen Tetley. Taylor’s ballets, including the sublime Transfigured Night (1980), were well received, and choreographic workshops fleshed out what became a sumptuous array of modern dance, from Bruce’s expressionistic Ghost Dances (1981), protesting the disappearing of Argentinian civilians, to Tetley’s seminal work, Pierrot Lunaire (1962).

Elizabeth Cameron Dalman at Mirramu Creative Arts Centre, Lake George, 1992 (photograph by Ross Gould, National LIbrary of Australia)The end of Victorian joint-funding for ADT in 1984 cut deep across Taylor’s budget and touring. Inevitably, tensions arose over a costly new Philip Glass ballet, presciently titled A Descent into the Maelstrom (1986), and already in the pipeline for Anthony Steel’s imminent Adelaide Festival. Steel and rehearsal director Lenny Westerdijk (a close friend on Taylor’s team) took over and Taylor left with all his ballets, and those lent by his friends. The board had assumed that the rights to the repertoire of sixty-five works, sixteen of them Taylor’s, belonged to ADT, leaving Leigh Warren to start from scratch, but without the older Taylor’s hard-earned know-how, and with a deficit of approximately $90,000.

Elizabeth Cameron Dalman at Mirramu Creative Arts Centre, Lake George, 1992 (photograph by Ross Gould, National LIbrary of Australia)The end of Victorian joint-funding for ADT in 1984 cut deep across Taylor’s budget and touring. Inevitably, tensions arose over a costly new Philip Glass ballet, presciently titled A Descent into the Maelstrom (1986), and already in the pipeline for Anthony Steel’s imminent Adelaide Festival. Steel and rehearsal director Lenny Westerdijk (a close friend on Taylor’s team) took over and Taylor left with all his ballets, and those lent by his friends. The board had assumed that the rights to the repertoire of sixty-five works, sixteen of them Taylor’s, belonged to ADT, leaving Leigh Warren to start from scratch, but without the older Taylor’s hard-earned know-how, and with a deficit of approximately $90,000.

Warren’s trajectory from The Australian Ballet, to The Juilliard School, Ballet Rambert, and Nederlands Dans Theater, prepared him to train his dancers to be versatile and strong enough to take on any style. With a smaller ensemble Warren investigated new territory. His productions were intriguing, ambitious, and, inevitably, uneven. On reflection with Tonkin, Warren felt that by privileging other artists’ work, he had undermined his own choreography. On learning that his contract would be cut short, he went out with a bang – a punk-baroque work Tuttu Wha, an extravagant pageant of dance, celebration, and defiance.

Meryl Tankard, who left The Australian Ballet to join (and be liberated by) Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal in Germany, became even more adventurous on transferring her Canberra company of women to Adelaide, along with a catalogue of striking works. Her biggest successes, the solo Two Feet (1988) and Furioso (1993) her first ADT work for expanded company, were worlds apart. Two Feet meditated on the art of ballet through Tankard’s own experience and that of the once-perfect Giselle, Olga Spessivtseva, a star of the Imperial Russian Ballet. In Furioso, her first Adelaide creation, dancers abseiled up walls, flew wildly around on ropes, and tobogganed across the stage on their bellies. Two Feet won her Australia’s respect; Furioso elevated her position among international presenters, including the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Lyon Opera. Tankard, too, was soon terminated after five years, her apparent sin being to have made ADT successful overseas, the brief she believes she was given.

Meryl Tankard (photograph by Regis Lansac, ACT Heritage Library image 007264 , Canberra Theatre Trust Collection)

Meryl Tankard (photograph by Regis Lansac, ACT Heritage Library image 007264 , Canberra Theatre Trust Collection)

Bill Pengelly, a respected rehearsal director who succeeded Tankard for a year, worked with just ten dancers to create a rewarding, year-long program that might even have landed him the directorship. But Garry Stewart’s more investigative vision of the future earned him the job. Stewart’s directorship reads like a continuation of Tankard’s, with an outstanding international presence and reputation. Entering dance at twenty for a year at The Australian Ballet School, and creating new work alongside Gideon Obarzanek’s Chunky Move, his aesthetic is driven by high-end digital media and explosive energy, scientific collaborations with the arts, from robotic or prosthetic compositions to deconstructing the classics in esoteric ways, but always with thrilling (or alarming) results. However, his potential to tour Australia was curtailed when Made to Move, Playing Australia’s touring program, was axed early in his term, but Europe keeps calling. How his long, productive tenure (already seventeen years) will be evaluated in future remains to be seen.

Comments powered by CComment