- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

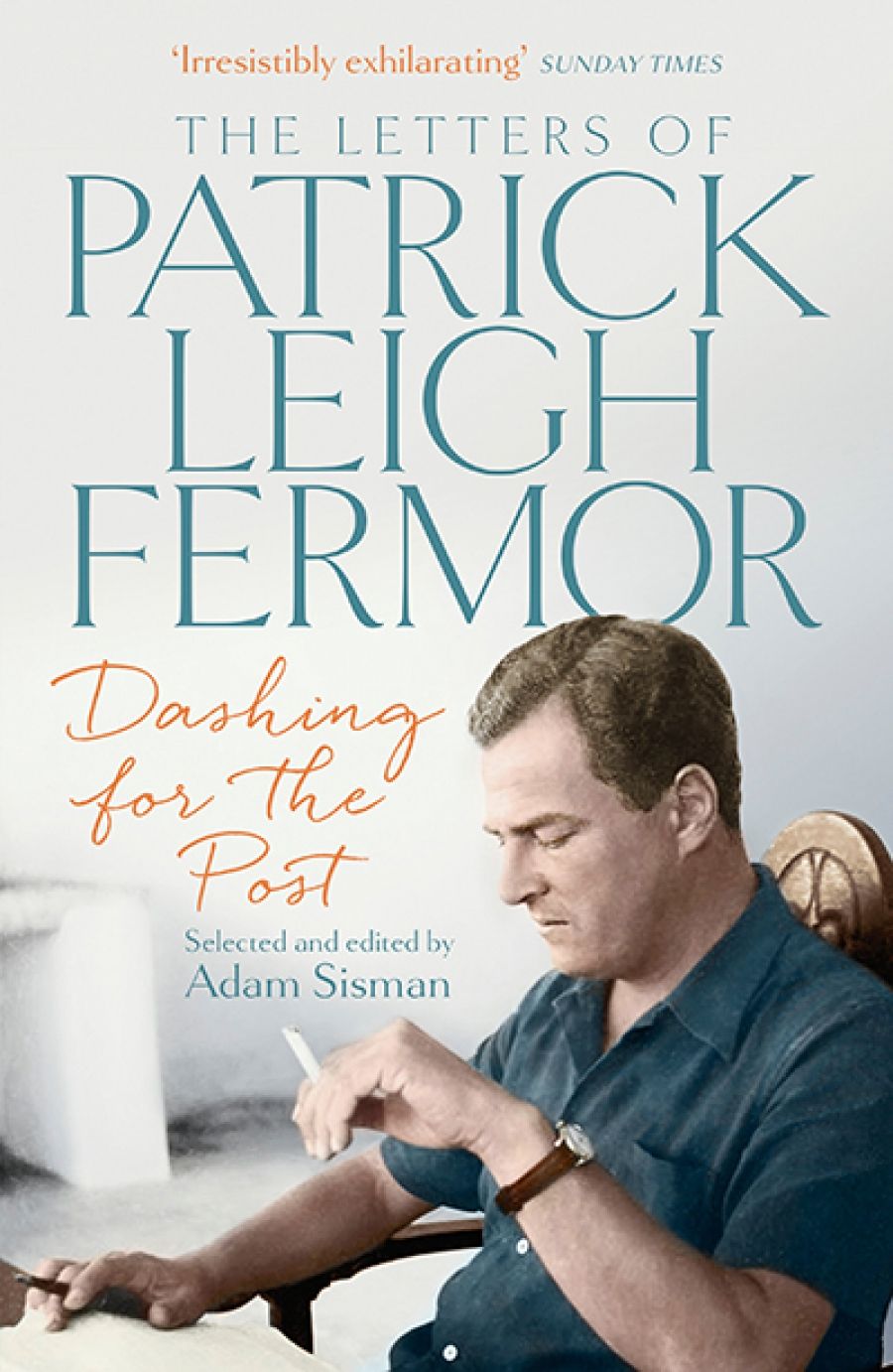

- Custom Article Title: Ian Britain reviews 'Dashing for the Post: The letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor' edited by Adam Sisman

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Absolutely charming – slim, handsome, nice speaking voice and manner, a super-gent’: it might be a line from an old-fashioned dalliance column, but it is from one of the letters published in this volume, and Patrick Leigh Fermor, writing to one of his most regular and lustrous correspondents, Debo Devonshire, youngest of the ...

- Book 1 Title: Dashing for the Post

- Book 1 Subtitle: The letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor

- Book 1 Biblio: John Murray, $35 pb, 492 pp, 9781473622470

Within the circles of celebrities – social, artistic, intellectual – to which Fermor gained an entrée in the wake of his war hero’s exploits, there were only a few who were not susceptible to his bewitching glamour. Judging from this selection of his letters (admittedly only a tenth or so of the total count), women generally swooned or fawned before him, and so did some of the men, though Somerset Maugham, Maurice Bowra, and Steven Runciman, for varying reasons, failed to be impressed. The letters themselves ooze such charm that it is hard for modern readers to resist without seeming mean-spirited or envious, and they display in casual form the nice writing voice and lightly worn erudition in history and languages that marked Fermor’s much fêted books recounting his travels across Europe and parts of South America.

Yet, cumulatively, the letters also betray the limitations and costs of what Cyril Connolly dubbed ‘the gland of charm’. ‘Comparatively innocuous’ as they might appear to the editor of this volume, there is something creepily compulsive about Fermor’s ingratiations with A-list celebrities and his obsessions with titles and pedigrees. His first long-term girlfriend, a princess of an ancient European line, and his later long-term partner, subsequently his wife, who came of aristocratic stock in England (‘beaucoup de race’, Fermor stresses at one point) emerge as far less snobbish than he. And behind his elaborate mea culpas for lapses in his personal or professional conduct, there is an air of calculation and gush. That is partly how charm works, and to a point it worked well for him in various ways: his publishers were willing to extend their deadlines for him seemingly endlessly, his girlfriends on the side could forgive him when he neglected or abandoned them, his wife (or, at the time, wife-to-be), in order to save him the embarrassment of constantly asking her for money, set him up with a regular income. But indulgence on this scale only encouraged him the more, it appears. He was spoiled in all senses of the word.

The letters are an unrelenting chronicle of self-indulgence in love affairs and gourmandising. It was the women who paid with their hearts for the former; and there was always someone else, whether wife or rich host, to pick up the tab for the banquets and feasts. He enjoyed home cooking, too, though you would never find him in the kitchen. It was canny of a newspaper editor, when commissioning a series of articles from famous authors about the Seven Deadly Sins, to give Fermor the choice of writing on gluttony or lust. He plumped for gluttony, he quipped, ‘because Lust is too serious a matter’. We can’t afford to be too judgmental here; how many of us, given his opportunities, and the prevailing values of his milieu, would have been able to restrain ourselves in either department? Yet, as he knew himself in moments of deeper self-reflection, he ran the risk of appearing more super-operator than super-gent: a ‘shit’ or a ‘rotter’, to use his lingo. And we are entitled to regret the opportunities he missed, as a result of his hedonistic excesses, to give fuller rein to his gifts as a writer.

Patrick Leigh Fermor (Wikimedia Commons)

Patrick Leigh Fermor (Wikimedia Commons)

In truth, given all the distractions and procrastinations, his was not an exiguous productivity rate: eight or so travel books in his lifetime, several of them acclaimed, plus a novel. But he could never settle down to finish his magnum opus, an account of his first ‘trudge’ across Europe in 1933–34 – two volumes had appeared by 1986, and those had to be dragged out of him; a promised third was eventually stitched together by friends after his death at the age of ninety-six in 2011. All they had to work from was a tangle of fragmentary and near-illegible drafts. To the end, and beyond, he remained adept at landing on other people’s feet. And who can know what other books he may have been capable of producing, over a very long life, if not infected with that ‘creamy’ charm pilloried by Evelyn Waugh’s Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited (1945)?: ‘Charm is the great English blight ... It spots and kills anything it touches. It kills love; it kills art ...’

Comments powered by CComment