- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biology

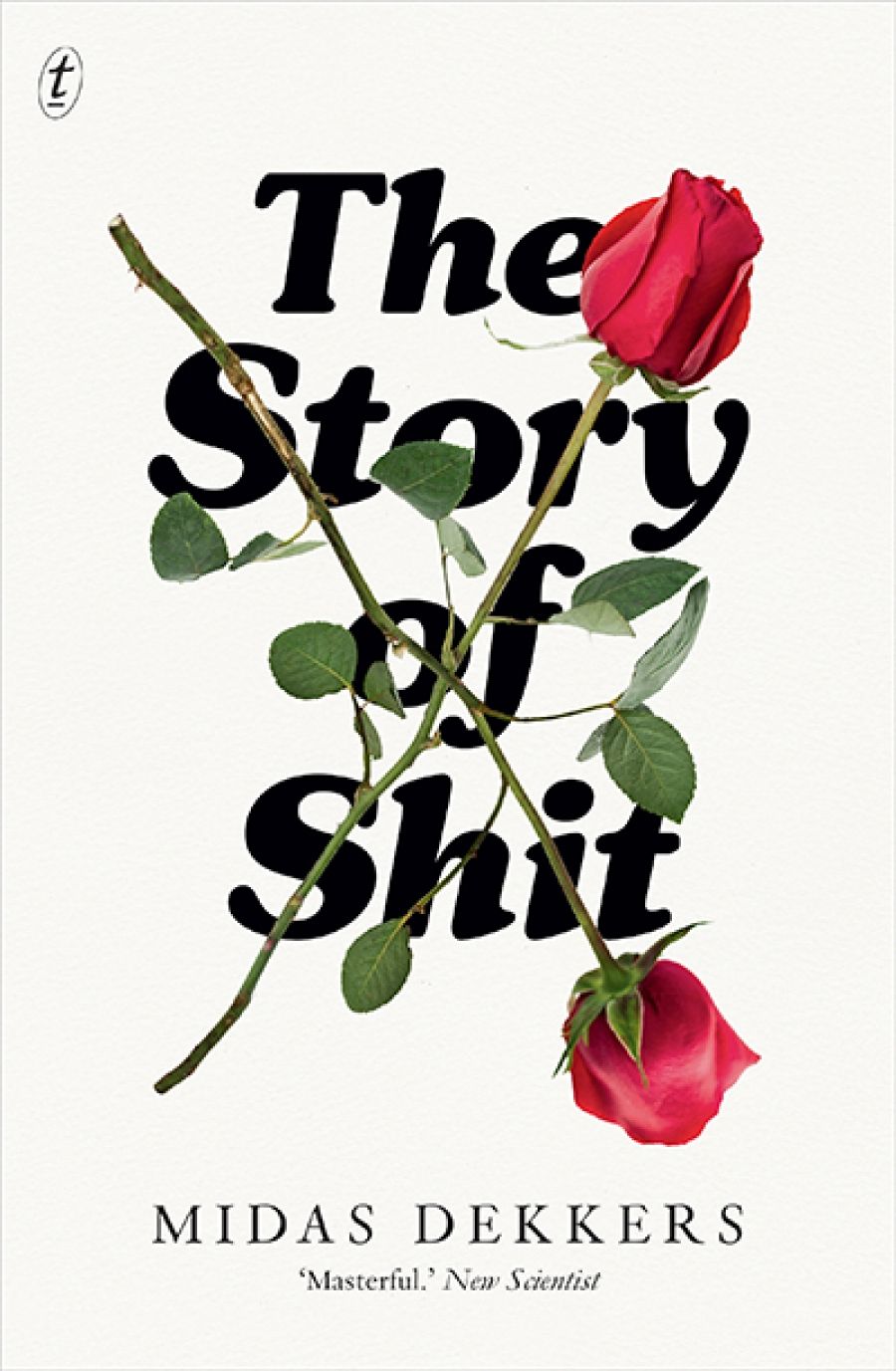

- Custom Article Title: Lauren Fuge reviews 'The Story of Shit' by Midas Dekkers, translated by Nancy Forest-Flier

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘People who write books about shit are regarded with suspicion,’ declares Dutch biologist and writer Midas Dekkers. But like the dung- beetle-worshipping ancient Egyptians before him, Dekkers understands a fundamental truth: ‘The world is round and held together by shit.’ ...

- Book 1 Title: The Story of Shit

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 293 pp, 9781925355178

Seemingly no topic is off-limits. All are treated with Dekkers’ forward personality and brazen prose: he writes as he talks. He revels in using language to shock, playing into the reader’s squeamishness and making them challenge their own disgust. It is delightfully freeing to read ‘shit’ and ‘turd’ freely scattered across every single page, but Dekkers also casually throws in ‘cunt’ or ‘coolie’. On the whole, though, the conversational style is enjoyable, packed with humour and metaphor. In one memorable chapter, the reader is taken on a visceral trip through the ‘black box’ of our body, following food’s journey from mouth to anus. The stomach becomes:

a single station on a long underground line that starts at the throat, dives through the oesophagus … and, after a long and winding ride through the small intestine via the Caterpillar ride of the large intestine … arrives at Anus Station, its final destination. One way only; no return tickets available.

Dekkers does, however, constantly double up on metaphors; in the space of a couple of pages, the stomach is referred to not just as a station, but a ‘warehouse’ and a ‘waiting room’ with ‘snacks available’, a quirk that becomes exhausting when every object is explained multiple times. It should be mentioned that The Story of Shit was translated from the original Dutch by American-born translator Nancy Forest-Flier. Since it is packed with a world of toilet-related slang, this was no trivial feat, but Forest-Flier masterfully keeps Dekkers’ spirited language intact.

The book is also filled with brown-gold nuggets. Over coffee with friends, you can explain that the sought-after Kopi Luwak coffee is actually the poop of Asian civets; or at a dinner party, you may muse about how nineteenth-century Englishman Dean Buckland was known for collecting fossilised turds and showing them off to his guests. Over tea with your grandmother, you can explain that elderly people are often thin because ‘the papillae in the intestines that absorb food get worn out, so that more food is transported unused’. At the beach, you can enthuse about how biologist Richard Martin calculated that ‘all the whales together fart a gigantic 200 billion litres a day’.

The inclusion of so many fascinating gems makes it all the more frustrating when Dekkers wanders off track. His conversational style may be easy to read, but it also produces meandering prose, unrelated stories, and repetitions – as most of us are guilty of in everyday conversation. At one point, for example, Dekkers embarks on a long-winded discussion of the shape, colour, and composition of sausages, only to eventually make the enlightening point that sausages and turds are remarkably similar.

Dekkers also makes bizarre choices, such as when he describes growing up as ‘innocent children’s tissue’ being ‘transformed into a tremendous penis or massive breasts’. Later, he declares that ‘it can be tempting to see your own turd as a living animal’, but laments that ‘what a turd lacks in order to be numbered among nature’s living creatures, besides four legs, is reproduction’. The statement’s utter absurdity makes the humour fall flat.

Midas DekkersThe book is also speckled with unsolicited personal judgements – whether or not to swaddle newborn babies, eat brains, feed your child commercial baby food, or eat a vegetarian diet. Dekkers even has a short tirade about technology: ‘Armed with their mobile phones, people have demanded the right to spout their drivel at the slightest pretext.’ It is frustrating that pages are wasted in this way when a more rigorous edit would have resulted in a book that was a third shorter but more enjoyable for it.

Midas DekkersThe book is also speckled with unsolicited personal judgements – whether or not to swaddle newborn babies, eat brains, feed your child commercial baby food, or eat a vegetarian diet. Dekkers even has a short tirade about technology: ‘Armed with their mobile phones, people have demanded the right to spout their drivel at the slightest pretext.’ It is frustrating that pages are wasted in this way when a more rigorous edit would have resulted in a book that was a third shorter but more enjoyable for it.

Some of this space could have been repurposed for a better cause: science. Since Dekkers is a biologist, I expected a better treatment of the science of shit than what was delivered. Such topics tend to be inserted as throwaway thoughts and jargon pops up without explanation, like the contextless statement that ‘in the small intestine the waste turns yellow from bilirubin’, then ‘bacteria convert it into urobilinogen, which oxidises into stercobilin’. It reads as if Dekkers is rushing to get away from scientific terms, when a mere half a sentence would have explained them perfectly adequately.

As a reader who loves a good footnote, I also found Dekkers’ referencing lacking. Though the appendix is packed with sources, they aren’t linked to his claims throughout the book, which was frustrating in the countless moments I was left staring at a sentence, wondering whether the seemingly outlandish claim was really true.

On the whole, The Story of Shit is an enjoyable romp through culture, science, and history. It reads like a casual and often crude chat with a knowledgeable mate whom you sometimes want to shake when he launches into yet another ten-minute tangent.

Comments powered by CComment