- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Psychology

- Custom Article Title: Nick Haslam reviews 'The Lost Boys: Inside Muzafer Sherif’s Robbers Cave experiment' by Gina Perry

- Custom Highlight Text:

Social psychology has a few iconic experiments that have entered public consciousness. There is the shaken but obliging participant who delivers potentially lethal electric shocks to another person in Stanley Milgram’s obedience research. There are the young Californians who descend into an orgy of brutality and ...

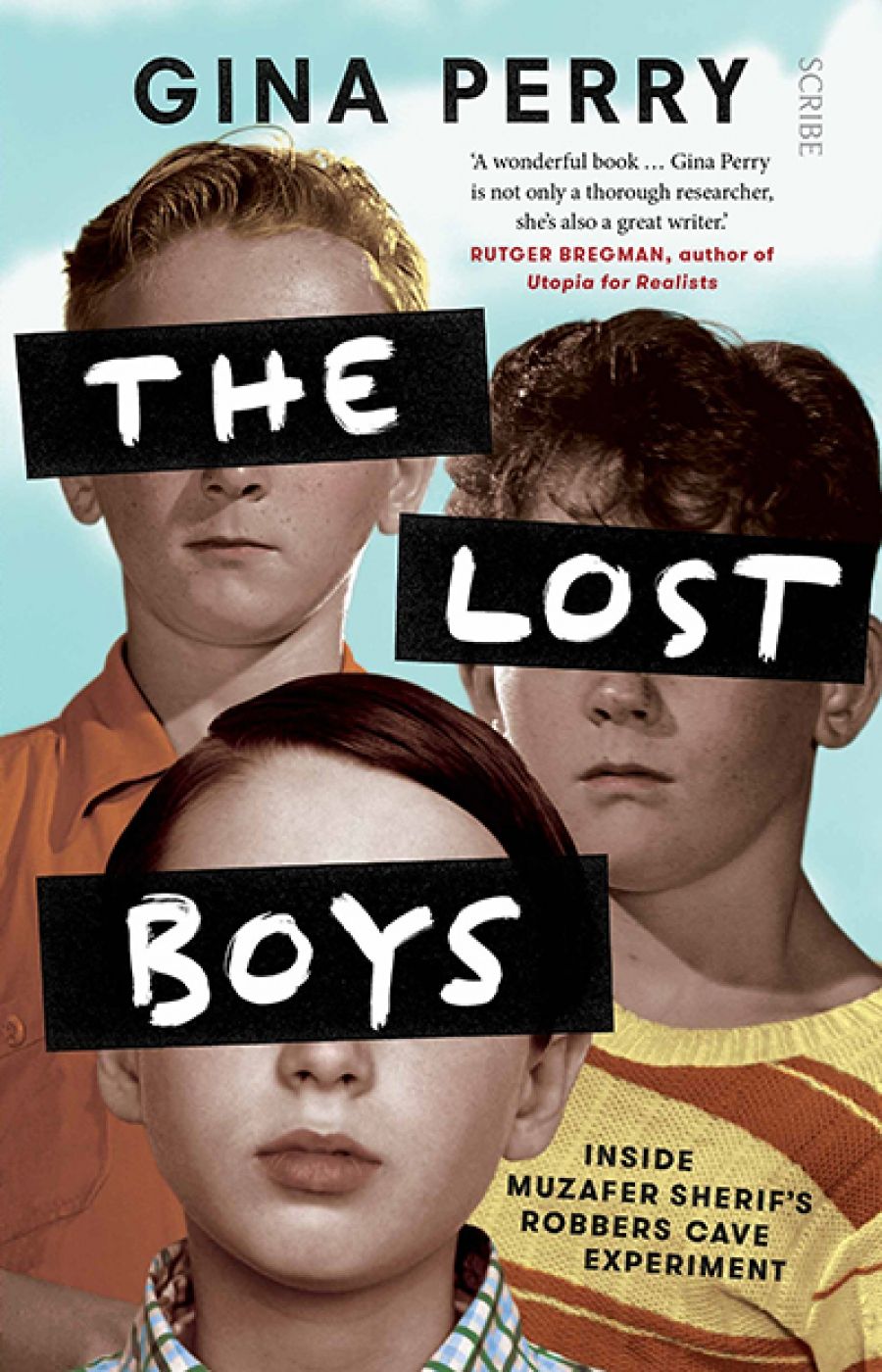

- Book 1 Title: The Lost Boys

- Book 1 Subtitle: Inside Muzafer Sherif’s Robbers Cave experiment

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.99 pb, 400 pp, 9781925322354

In her penetrating book Behind the Shock Machine (2012), Australian psychologist Gina Perry exposed the disturbing underside of Milgram’s obedience research. Her interviews and archival inquiries revealed the harm Milgram did to some of his participants, the ethical shortcomings of his work, and the disturbing discrepancies between how the studies were conducted and how they were presented in the scientific literature. In her new book, The Lost Boys, Perry turns her attention to a line of second-tier research and sounds some similar critical notes. Muzafer Sherif, an increasingly forgotten figure of mid-century American social psychology, comes off only slightly better than Stanley Milgram, and in Perry’s verdict his most famous study has limited value.

Robbers Cave was a field study, conducted in rural Oklahoma in 1954, that aimed to test Sherif’s theories about the origins and resolution of inter-group conflict. With a team of junior associates, he took twenty-two carefully selected eleven-year-old boys for a summer camp that was organised into three phases. The boys started the camp in two separated groups and spent a few days forming bonds. The groups were then brought together for a series of competitive challenges that became increasingly hostile, inflamed by the research team’s orchestrated provocations. In the final ‘integration’ phase, the tensions were relieved by shared activities that united the groups in cooperation. As it is normally presented in textbooks, the study offered early support for ‘realistic conflict theory’, according to which prejudice is driven by competition over resources, social contact alone – as in multiculturalism – is not sufficient to overcome inter-group frictions, and the pursuit of shared, superordinate goals is the key to reconciliation.

Perry turns a sceptical eye on this uplifting gloss, and tells the story based on interviews with Sherif’s associates and former ‘lost boys’ and a recently released trove of records. Before turning to Robbers Cave itself, she uncovers a nearly identical study that Sherif conducted in 1953 which was aborted and then suppressed when it failed to go to plan. In her reconstruction of Robbers Cave she shows how the group dynamics were engineered by the research team’s interventions, and how the boys’ awareness of being manipulated complicated those dynamics. Perry argues that these interventions make the study a biased attempt to confirm rather than test Sherif’s hypotheses. Similarly, because the researchers functioned as a third group, Sherif was wrong to frame Robbers Cave as a binary study of us versus them.

Perry is decidedly unsympathetic towards Sherif as a person. He was certainly hard to love: temperamental, arrogant, dictatorial, obsessed with his work, and resentful that he had not received the accolades he felt he deserved (a near-universal private grievance among academics). Some of these failings take on a different cast in light of his late-life diagnosis of bipolar disorder and a significant brain injury he suffered as a child in Turkey after being kicked unconscious by a camel. Sherif also faced the heartache of seeing that country erupt in ethnic atrocity as a young man and close its door on him as an older one. He experienced anti-communist persecution in his adopted country, where J. Edgar Hoover set the FBI onto him. Although Perry’s portrait of Sherif is rich in historical detail, it is painted in cool colours.

A still from '5 Minute History Lesson, Episode 3: Robbers Cave', showing some of the boys selected for the Robbers Cave experiment (Cummings Centre for the History of Psychology)

A still from '5 Minute History Lesson, Episode 3: Robbers Cave', showing some of the boys selected for the Robbers Cave experiment (Cummings Centre for the History of Psychology)

Perry’s reading of Sherif’s work is also a little ungenerous and dismissive. She is rightly troubled by the deception and ‘casual cruelty’ of the Robbers Cave study, but these aspects were typical of research with human participants at the time. Principles of research ethics were sketchy, oriented to medical experimentation, and not yet applied in formal reviews. We might wish that Sherif had been more compassionate and enlightened, but it is questionable to apply contemporary standards to work carried out sixty years ago. Equally, Perry sometimes presents Sherif’s ideas as if they were self-evident and his studies as too flimsy and artificial to justify claims of relevance to real-world conflicts, writing off Robbers Cave as ‘a Cold War bedtime story to give people hope in a time of fear’. Although it would indeed be absurd to imagine that the squabbles of pre-teen boys are equivalent to the struggles of nations or ethnic groups, it is not absurd to explore mechanisms of animosity and its alleviation on a small scale.

According to its epigraph, no social science is more autobiographical than psychology, but The Lost Boys never quite settles on how Robbers Cave reveals the truth of Muzafer Sherif. Was it an attempt to wrestle with the convulsive conflicts of his youth, an expression of an immigrant’s feelings of alienation, or the pseudo-scientific project of an ambitious monomaniac? Perry may not have all the answers, but she has written an enthralling exploration of the question.

Comments powered by CComment