- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Jake Wilson reviews 'Warner Bros: The Making of an American movie studio' by David Thomson

- Custom Highlight Text:

David Thomson has been an essential writer on film for around half a century, but in certain circles his reputation has long been in decline. The reasons are obvious enough. He writes too much, and sometimes carelessly; he lets his feelings run away with him; an Englishman who followed his dream to the United States ...

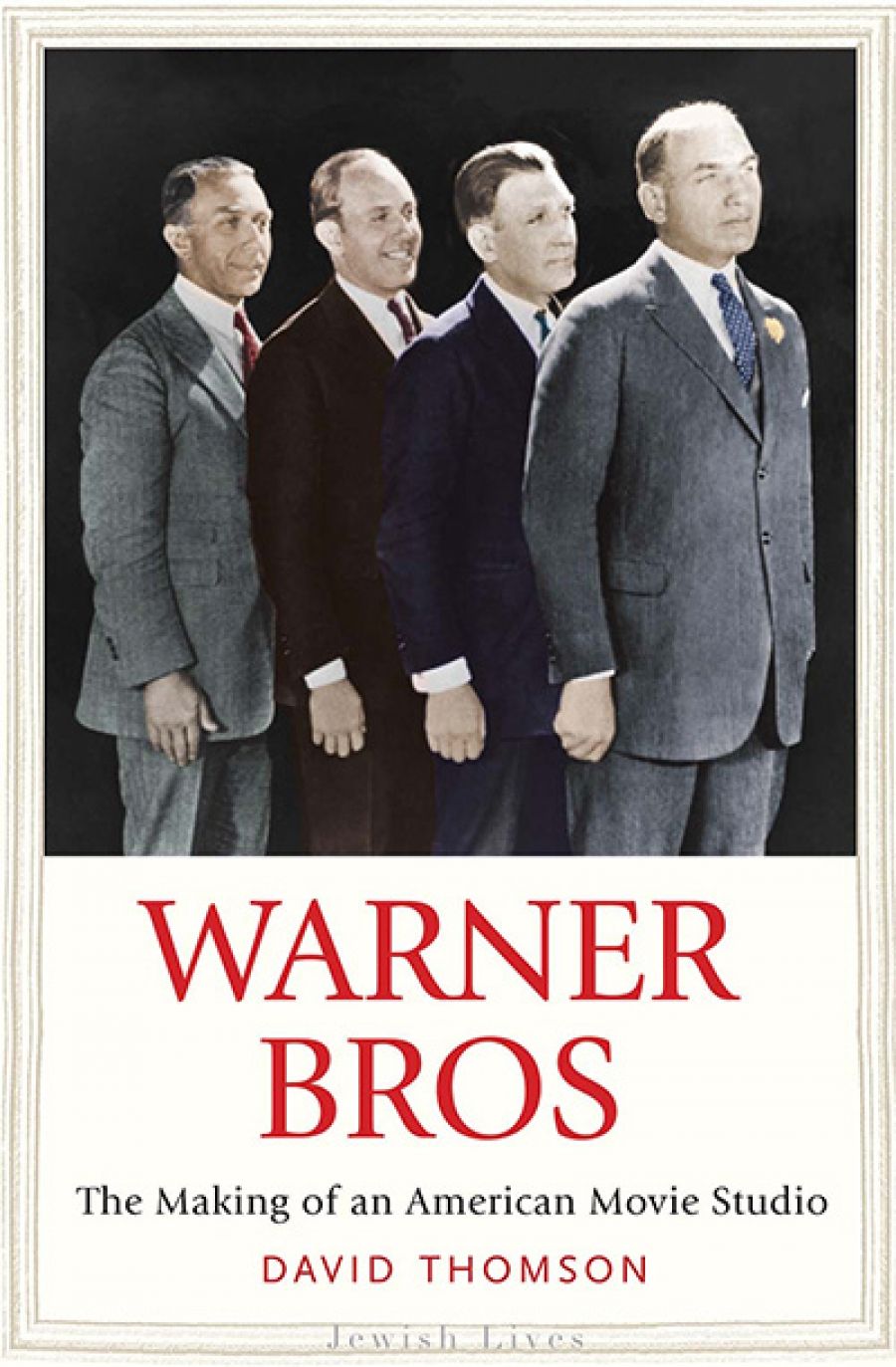

- Book 1 Title: Warner Bros

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Making of an American movie studio

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $39.99 hb, 220 pp, 9780300197600

These weaknesses are by-products of Thomson’s greatest strength, which is that all his work is fuelled by passion: his many books on cinema are the record of a long, one-sided, and often agonised love affair. This includes Warner Bros, misleadingly packaged as the latest in the Jewish Lives series of ‘interpretative biographies’ from Yale University Press. This is far from being a definitive biography of the four immigrant brothers (originally the Wonsals) who founded and gave their name to one of the great Hollywood studios. But it is a fine example of Thomson’s loose, essayistic method, which consists of letting his thoughts wander and seeing what insights turn up.

As he underlines, the book is called Warner Bros rather than Warner Brothers, leaving us with the somewhat tedious puzzle of whether this is ultimately the story of a family or a studio and to what extent the two stories coincide. Clearly, the significance of Warners as a brand was not determined solely or even primarily by the business-minded brothers, in no sense artists and not too encouraging of open attempts at artistry (they had little use for Ernst Lubitsch, who decamped to Paramount just before the coming of sound). On the other hand, by the early 1930s Warners had established a tough, fast, irreverent house style which was not the property of any single individual: to explain where this came from, it makes sense to begin with the guys at the top.

This is what Thomson does, although his method is always to look for the myth underlying the facts rather than vice versa. Relying more on poetic intuition than research, he homes in on the two brothers central to Warners in its heyday, highlighting their differences as if they were rivals in a melodrama (family feuds, we are reminded, were a popular plot device at Warners, though possibly no more so than elsewhere). The respectably conservative Harry Warner, based in New York, was the company president, but Harry’s younger brother Jack, head of production in Los Angeles, was the real force behind the scenes. Jack is the brother Thomson loves, with his wisecracks, his pencil moustache (predating Errol Flynn’s), and his vulgar confidence about what the public might be persuaded to buy. The book paints him as a borderline crook and unambiguous sexual predator, but also as the dynamic spirit of the studio incarnate. Indeed, for Thomson he appears to personify something essential about the very nature of cinema, as well as about the United States – linked, in both cases, with the drive toward self-reinvention otherwise known as the American Dream.

Sam Warner, Joe Marks, Florence Gilbert, Art Klein, Monty Banks, and Jack Warner 1920 (Exhibitors Herald, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sam Warner, Joe Marks, Florence Gilbert, Art Klein, Monty Banks, and Jack Warner 1920 (Exhibitors Herald, via Wikimedia Commons)

There are moments here when Thomson, who has published a couple of novels, seems on the verge of writing one about the Warners. Perhaps someday he will. Or perhaps he will find inspiration in another pair of brothers, the Weinsteins, whose story in so many ways is the spiritual sequel to this one. Fiction, however, would leave little room for the extended critical riffs that take up a large portion of the book. These show that Thomson still has the nearly unique ability to write about movies in words that have some of the spontaneous magic of the films themselves, and to revivify the reader’s own memories, even when he is discussing something as shopworn as Casablanca (1942). He writes well about Howard Hawks and Busby Berkeley, about Al Jolson and James Cagney, about Rin Tin Tin and Bugs Bunny – and quite magnificently about Bette Davis, the heroine of the book, whose combative personality is seen as both the ultimate challenge to the Warners ethos and its ultimate embodiment (one chapter is titled ‘Bette v. Everyone’).

Jack Warner, 1955 (Wikimedia Commons)Running through the book like a drumbeat is Thomson’s ambivalence about the antisocial energy so abundant in Warners films, and so crucial in general to what cinema has meant to him over all these years. Like the late Pauline Kael, he is fond of the first person plural, but where Kael aimed to draw the reader into agreement, Thomson often gives the impression that he is speaking mainly for himself but is too shy to admit it. ‘We have always wanted to idealise gangsters, and that reveals something reckless in us, something that was catered to by the movies.’ If you say so, buddy. At other moments he turns pious, as if the ghost of Harry were looking over his shoulder: ‘We have long since exhausted the aura of old Hollywood, and there is no reason to romanticise it.’ That might be the least convincing sentence in the book, if the same paragraph did not go on to lament that the ‘romantic attitudes of movies hindered rational thought and social progress’. As if Thomson, in his heart, gave a damn for either.

Jack Warner, 1955 (Wikimedia Commons)Running through the book like a drumbeat is Thomson’s ambivalence about the antisocial energy so abundant in Warners films, and so crucial in general to what cinema has meant to him over all these years. Like the late Pauline Kael, he is fond of the first person plural, but where Kael aimed to draw the reader into agreement, Thomson often gives the impression that he is speaking mainly for himself but is too shy to admit it. ‘We have always wanted to idealise gangsters, and that reveals something reckless in us, something that was catered to by the movies.’ If you say so, buddy. At other moments he turns pious, as if the ghost of Harry were looking over his shoulder: ‘We have long since exhausted the aura of old Hollywood, and there is no reason to romanticise it.’ That might be the least convincing sentence in the book, if the same paragraph did not go on to lament that the ‘romantic attitudes of movies hindered rational thought and social progress’. As if Thomson, in his heart, gave a damn for either.

Comments powered by CComment