- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Philippa Hawker reviews '"La Parisienne" in Cinema: Between art and life' by Felicity Chaplin

- Custom Highlight Text:

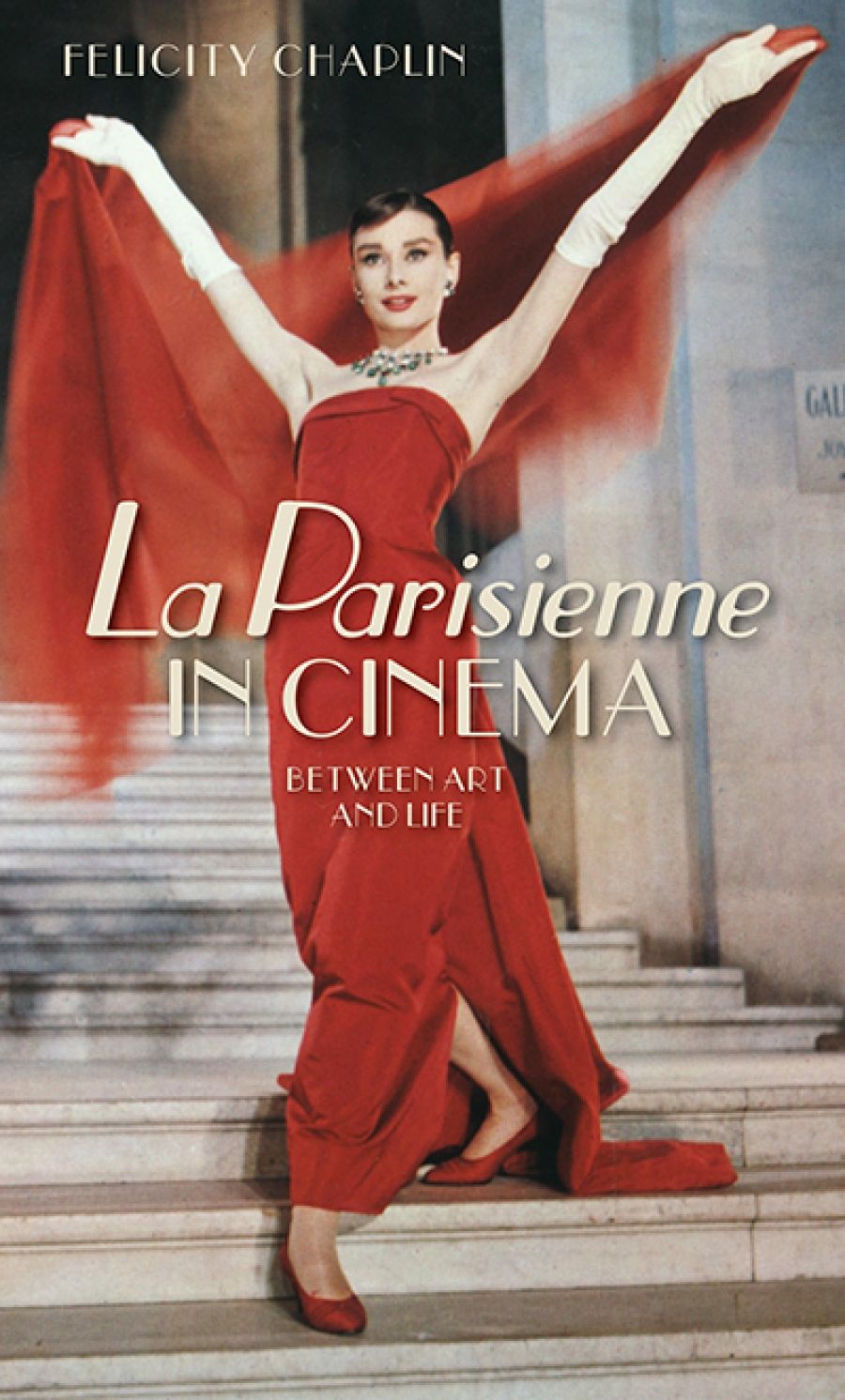

On the cover of Felicity Chaplin’s La Parisienne in Cinema: Between art and life, Audrey Hepburn, arms aloft, reigns triumphant in a strapless scarlet evening gown and organza shawl. This is a scene from Funny Face (1957), in which she plays a shy Greenwich Village bookshop employee transformed into a high-profile ...

- Book 1 Title: 'La Parisienne' in Cinema

- Book 1 Subtitle: Between art and life

- Book 1 Biblio: Manchester University Press (Footprint), $166 hb, 213 pp, 9781526109538

‘La Parisienne’, as Chaplin explains, stands for an image of the city personified by a female figure. In the mid-nineteenth century, this became synonymous with the figure of an urban woman, an emblem of modernity whose mode of dress expressed her identity. She can be both artist and muse. Her class origins are not fixed: she might come from the demi-monde or the bourgeoisie. In context, she can embody sexual openness and experimentation, or refined elegance and restraint.

Chaplin begins with a historical overview that locates the figure in art, fashion, literature, and popular culture, before examining her subject’s cinematic manifestations, an area of study that is surprisingly under-explored. Her Parisienne is not a stereotype but a type, ‘recognisable through certain recurring motifs, yet also constantly being reinvented’.

Chaplin’s embrace is catholic: she includes arthouse films, classics, popular movies, and lesser lights. She cites scores of titles, but focuses on twenty or so: of these, the earliest is Charlie Chaplin’s A Woman In Paris (1923); the most recent is Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris (2011). Many come from the 1950s or early 1960s, a period in which Hollywood was drawn to a certain image of ‘Frenchness’, in which the figure of the Parisienne played a significant part.

In six chapters, Chaplin defines six categories of ‘La Parisienne’, bringing her examples vividly to life. These are distinct but also elastic categories: examples can and do reappear under more than one heading. Some of her film choices emphasise themes that stretch across definitions. In the first chapter, on the muse, three very different films all make use of the Belle Époque as an era to conjure with, as do works in other categories. The section on the ‘Courtesan’, for example, includes Nicole Kidman, as the figure of Satine, in Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! (2001).

Anna Karina (Wikimedia Commons)

Anna Karina (Wikimedia Commons)

Her second chapter, on the ‘Cosmopolite’, reminds us that Paris is not simply a geographical location. Julien Duvivier’s 1937 crime drama Pépé le Moko is set in Algeria, and includes a character known as ‘Gaby the Parisienne’; Jacques Demy’s Model Shop (1969) gives us Anouk Aimée as the embodiment of Paris in Los Angeles; and another Hepburn film, Billy Wilder’s Sabrina (1954), in which her character’s makeover takes place off screen – the fact that she has been in Paris for two years is enough to explain her newfound elegance and desirability.

Chaplin has a chapter entitled ‘Icon of fashion’: self-fashioning is the emphasis, however, rather than couture and style, in this chapter and in others. It makes sense that Jean Seberg – a New Wave American in Paris in Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless) – is in this chapter: her cropped hair, T-shirt and cigarette pants are an enduring look. Yet, as a lover turned betrayer, she also belongs in the next category, ‘Femme Fatale’, alongside figures from classics by Marcel Carné and Jules Dassin. There is also a case for her to be included in the final chapter, ‘Star’. Here, Chaplin summons up images of four Parisiennes in four signature roles. She cuts from one to another, almost as if they are contemporaries in the same movie: Brigitte Bardot, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Anna Karina, and Jeanne Moreau, four actresses who, in different ways, bring elements of their off-screen life and image to their performances on screen. This narrative strategy emphasises a theme: the temporal fluidity of the Parisienne figure, her ability to exist in more than one era, to carry over her qualities from one decade to another, one world to another.

Audrey Hepburn and her pet poodle on the set of Sabrina (Flickr)In the case of Bardot and Karina, their movie work from the 1950s and 1960s has an enduring impact, a quotable visibility in fashion, film, and popular culture. Gainsbourg combines an It Girl cultural status with an appetite for challenging film roles and a music career on the side.

Audrey Hepburn and her pet poodle on the set of Sabrina (Flickr)In the case of Bardot and Karina, their movie work from the 1950s and 1960s has an enduring impact, a quotable visibility in fashion, film, and popular culture. Gainsbourg combines an It Girl cultural status with an appetite for challenging film roles and a music career on the side.

La Parisienne whets the appetite, invites further speculation. Chaplin acknowledges that her work is a starting point, and that there are many ways in which it could be taken further. She mentions Bande de filles (Girlhood ), Céline Sciamma’s 2014 coming-of-age film that focuses on a young black woman (Karidja Touré) intent on making a life beyond the limitations imposed on her. Chaplin’s definition, she says, ‘leaves room for Parisiennes from any number of national or ethnic backgrounds’.

In her deft, dense, intriguing book, Chaplin has delineated an area of research; she has also created a space or set of possibilities for studies that can take her project further, deeper, into more specialised areas or specific forms of critical engagement.

Comments powered by CComment