- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

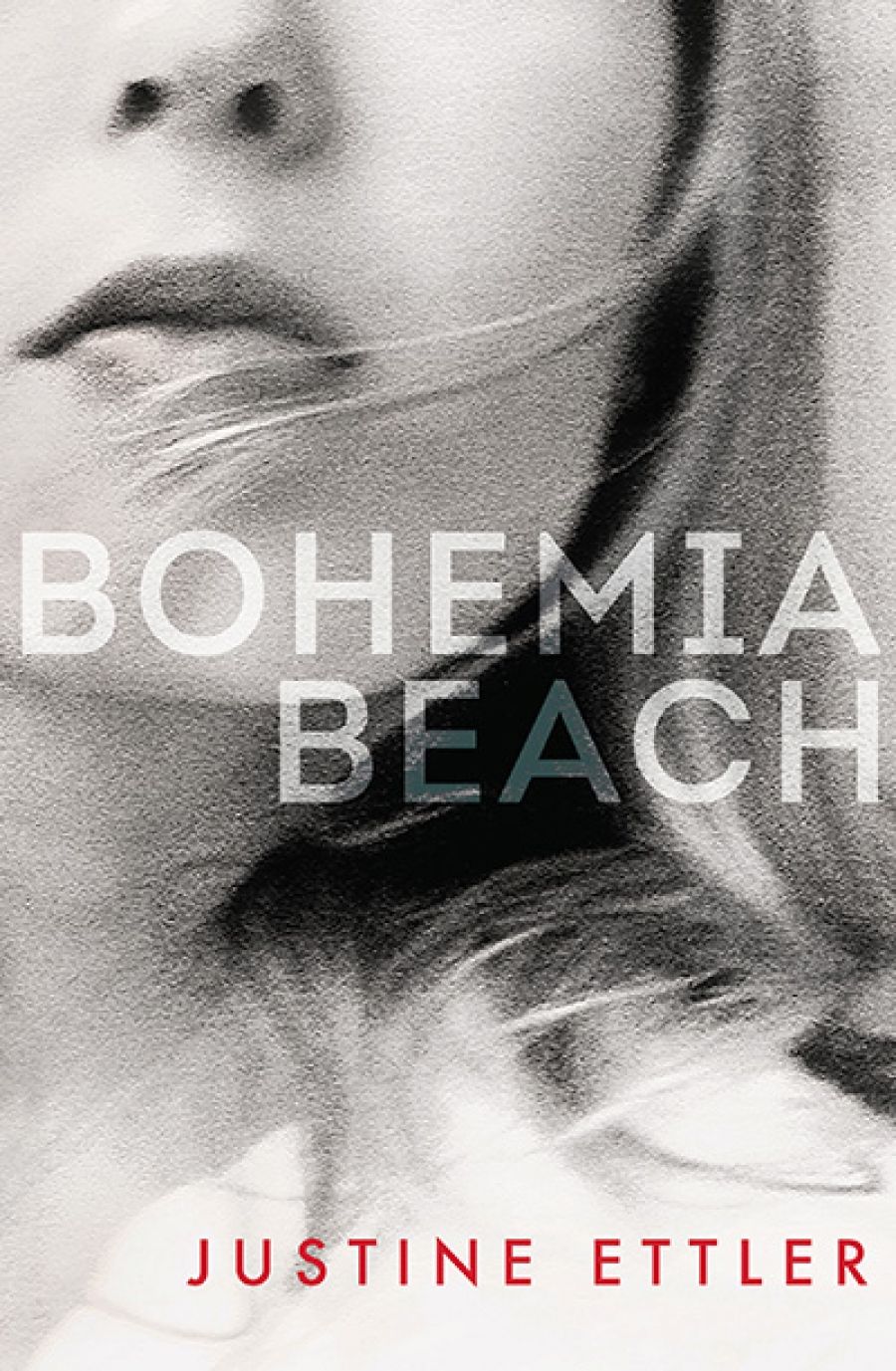

- Custom Article Title: Fiona Wright reviews 'Bohemia Beach' by Justine Ettler

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Bohemia Beach is a highly anticipated novel – the first work by Justine Ettler in twenty years. In many ways, it is a continuation of her oeuvre: a fast-paced, almost madcap tale about a wildly careening woman and the violent men she is drawn to, with obsession and addiction driving much of the narrative and narration ...

- Book 1 Title: Bohemia Beach

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 pb, 324 pp, 9781925760002

These names are deliberate references to Wuthering Heights, and there are other characters, in Prague, named after counterparts from Czech writer Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being: Tomas, Franz, and Sabine. Indeed, Cathy also adopts the name Tereza – her middle name – while she is in Prague, in part in homage to this text. This is a technique also at work in Ettler’s first novel, The River Ophelia (1995), whose two main characters bear names drawn from the text that informs its story of sexual obsession and power play, the Marquis de Sade’s novel Justine (1791), which in turn informs the narrative that Ettler superimposes upon it.

It is not hard to see other similarities here too. Cathy, like Justine, is attracted to unkind and uncaring men who treat her badly; both characters rely on a steady supply of drugs to keep their equilibrium, both feel powerless within their own lives, trapped and unable to change. At times, even the narration of both characters is similar – in The River Ophelia, Justine states: ‘What’s wrong with me? […] Nothing can help me […] I’m never going to be happy. I’m never going to believe I can be happy. I’m never going to be in control of my life.’ This sentiment is echoed in Bohemia Beach by Cathy, speaking on the telephone to Nelly, ‘I can’t keep doing this … And it’s always like this … I’ve tried and tried […] But there’s just no point – it always turns out the same.’

Ettler’s gritty, punky aesthetic, one of the strongest characteristics of her earlier works, is also present in Bohemia Beach, but it is complicated here, and made more complex, by frequent irruptions of the Gothic. Often, this is expressed through landscapes, and especially buildings: many of the key events take place within a dilapidated castle, belonging to Tomas’s family, and with a long history of dispossessions and repossession; elsewhere, there is a bedroom with a ‘secret passageway’ and a library full of H. Rider Haggard and M.R. James ghost stories, a Prague nightclub with a hidden room for special guests. But it is an updated kind of Gothic, explicitly, rather than just implicitly, linked to repressed or ‘original’ traumas, be they family secrets, unexpressed for many years, or broader histories affecting the entire nation of the Czech Republic. These two scales of trauma converge on the figure of Odette, Cathy’s mother – a Czech dancer who migrated to London during the communist era, and whose history is one of the central mysteries of the book.

Justine EttlerThese secrets and palpable ambiguities give the book much of its energy – it feels, at times, like a psychological thriller, albeit a remarkably intelligent one – and they also make it an intriguing read. Ettler is interested in the subjective and the irresolute, and also in shaping a female narrator who is both unreliable and often unlikeable – and these are both refreshing and bold choices, and important politically, as well as aesthetically. At times, Cathy’s drunken and self-deluded stream-of-consciousness narration can become overbearing, especially as it is often circular, often fixated on alcohol and men – but this is to be expected, given that these are the two objects of her addictions. Similarly, not all of the dream-states and -scapes that she describes are entirely successful. But Cathy’s voice is strong, and distinctive – frantic but often funny, hurting but holding it together, if only for now.

Justine EttlerThese secrets and palpable ambiguities give the book much of its energy – it feels, at times, like a psychological thriller, albeit a remarkably intelligent one – and they also make it an intriguing read. Ettler is interested in the subjective and the irresolute, and also in shaping a female narrator who is both unreliable and often unlikeable – and these are both refreshing and bold choices, and important politically, as well as aesthetically. At times, Cathy’s drunken and self-deluded stream-of-consciousness narration can become overbearing, especially as it is often circular, often fixated on alcohol and men – but this is to be expected, given that these are the two objects of her addictions. Similarly, not all of the dream-states and -scapes that she describes are entirely successful. But Cathy’s voice is strong, and distinctive – frantic but often funny, hurting but holding it together, if only for now.

Bohemia Beach, an ambitious novel, weaves together different modes and temporalities, and relies on gaps and absences as much as what is openly expressed to draw the reader along. A book of excess as much as it is about excess, it is every bit as raw and gripping as Ettler’s earlier works. Its wildness and energy are refreshingly offbeat, and unique in our contemporary fiction landscape. Ettler’s patient fans will not be disappointed.

Comments powered by CComment