- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

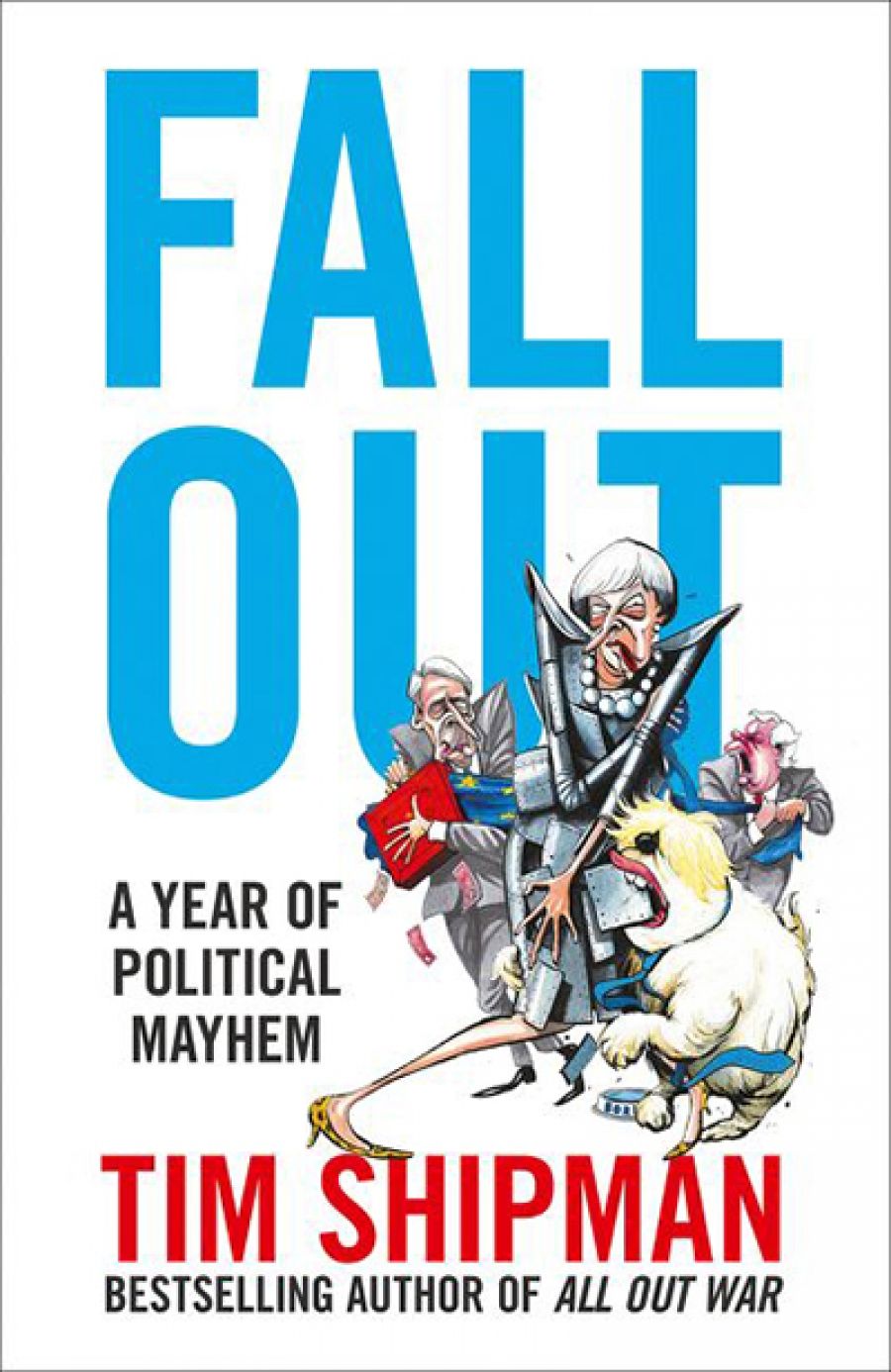

- Custom Article Title: Ross McKibbin reviews 'Fall Out: A year of political mayhem' by Tim Shipman

- Custom Highlight Text:

At present it is virtually impossible to make any confident prediction about the future of British politics, or indeed of the British state. The future lies in a fog where shadowy figures can be discerned but none is readily identifiable. Nothing should surprise us, but it now always does. This has been true since the 2015 ...

- Book 1 Title: Fall Out

- Book 1 Subtitle: A year of political mayhem

- Book 1 Biblio: William Collins, $57.99 hb, 592 pp, 9780008264383

Its result, of course, was also more or less unexpected. The referendum was technically non-binding and had no conditions attached to it. The majority of those who participated simply voted to ‘leave’ the EU. Their decision brought down Cameron’s government and with it all the Conservative Party’s alpha males, including those who desperately wanted to be prime minister. The candidate of the Daily Mail, Theresa May, was bizarrely and unanimously elected Tory leader. Having been a lukewarm remainer, she became a full-blooded leaver. She interpreted the referendum result in the ‘strongest’ possible way – the way the right-wing of the Conservative Party’s MPs and the living fossils who now mostly comprise what is left of the Party’s membership interpreted it. She therefore severely constrained herself in negotiations with the EU and with the remainers within the Conservative party. She knew this and decided that a second general election in two years was one way of freeing herself. This was an understandable decision. May had a huge lead in the polls; Labour was encumbered with an apparently unelectable leader; and a big victory would strengthen her leadership of the Conservative Party, increase in parliament the number of those who wanted a hard Brexit, and allow her to reconstruct her cabinet as she wished. We know, of course, that she, too, unexpectedly failed. In fact, the opinion polls were pretty accurate in their predictions of the Conservative vote, while May did very much better than David Cameron had ever done. What they did not predict – though their raw data did – was the huge surge in the Labour vote. This, in my view, was due to an accidental confluence of political circumstances and little to do with Jeremy Corbyn – though he and his supporters reasonably enough took the credit. To all these events there was a certain weird logic. Things unfolded naturally but with consequences quite the opposite of what was predicted.

Fall Out is concerned with the year 2016–17 (‘a year of political mayhem’ as the subtitle puts it): roughly speaking from the EU referendum to the general election of 2017 and its immediate political outcome. Tim Shipman, the political editor of the Sunday Times, is perhaps Britain’s best-informed journalist: he is the man all insiders will talk to or leak to, as is apparent from this large and detailed book. In big-picture terms he doesn’t tell us much we didn’t know; and what we don’t know simply cannot now be plausibly guessed at by anyone. But Shipman’s book is very revealing about the processes of government, and does much to undermine whatever confidence we still had in the way Britain is ruled.

At the centre of the story are the ‘spads’, the special advisers (who include press secretaries). They are everywhere: young men and women fascinated with the business of politics, but with little political experience or wider knowledge, for whom what really matters is tomorrow’s opinion polls. They ‘protect’ their ministers; that is, they marginalise them and often usurp their functions. Negotiations between departments are often, in practice, conducted spad to spad. Policy is frequently what the spads think it is, or wish it to be, and they report it as such to the press and their favourite journalists. They act to frustrate the senior civil service who are not regarded as friends.

The arch-spads, who are rather the stars of the book, are the ‘gruesome twosome’, Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, originally May’s advisers who were appointed her joint chiefs of staff when she became prime minister. They were devoted to May and what they took to be her interests. To them she had qualities others had not detected. But they almost infantilised her. As ‘gatekeepers’ they decided whom she should see, and usually only in their presence. On occasion she would absolutely not see a minister or civil servant in their absence. They were not altogether alike. Timothy was more thoughtful and interested in policy, whereas Hill seems to have been not much more than a political bully. But their combined behaviour (and their language) towards ministers and civil servants could be appalling. There is little doubt that even before the election they were widely disliked; and since someone had to be blamed for its comparative failure it was agreed that they were to blame. It was made immediately clear to May that they had to go, and they went. For May, this was probably no real loss. To the extent that she has gained some self-confidence since the election it is possibly because they are not there always to tell her what she should think and how she should behave.

Campaigners from Avaaz demonstrate after UK general elections (Avaaz, via Wikimedia Commons)

Campaigners from Avaaz demonstrate after UK general elections (Avaaz, via Wikimedia Commons)

How far they were responsible for the disappointing election is disputable. Timothy wrote the party manifesto, which was thought to have been hopelessly ill-conceived. But he seems to have believed that the Australian twosome, Lynton Crosby and Mark Textor (who do not come out of this story very well), were equally responsible. It was they who insisted that May rather than the party should be the absolute leading actor in the Tory campaign, a role for which she was not personally suited (as she knew and said so). It was they who also insisted that the utterly banal slogan ‘Strong ‘n’ Stable’ should be central to the government’s rhetoric: a curious echo of the equally vacuous ‘Jobs ‘n’ Growth’ that nearly did for Malcolm Turnbull. Shipman’s revelation of the extent to which the spads had inserted themselves into the business of government without anybody ever really deciding how and why they should has important implications for our political life. In their behaviour they have something in common with the referendums to which British politicians have resorted in the last few years. They are destabilising additions to a system of government, parliament, and civil service, for which these institutions were never designed. Recent evidence suggests that the spads are having the same effect on Australian government, which was equally never designed for them. There is little sign that politicians recognise this or that their reliance on the spads has in any way diminished.

Historians will no doubt make hay with the last eighteen months in British political life. Whether they will adequately explain it is something else. What they must explain is how a traditionally well-functioning and well-ordered state system should have gone so wildly off the rails. They cannot escape the utter recklessness and irresponsibility of the fantasists, xenophobes, and charlatans who have led the campaign to leave the EU; or, indeed, the wilful ignorance of those voters who made no attempt to understand exactly what the EU actually did or what the consequences of leaving it might be. The Brexiteers have never bothered to define exactly what they wanted or what alternatives were realistically available: one reason why the current negotiations with the EU have been so chaotic. For many the vote to leave represented a powerful emotional release which overrode, at least temporarily, any of the claims of economic or political reality. All you need is faith, and faith after all will move mountains. It was rather like the sense of emotional release that overtook the British cabinet in 1956 when it decided to use force to deny Egypt ownership of the Suez Canal. It was an emotional release to all those who found (and now find) the modern world and Britain’s reduced place in it too distressing to bear.

For others in the Parliamentary Conservative Party it is a game. And winning the game is all that matters since games are outside the reality of life. Westminster systems of government, Australia’s included, are very susceptible to game-playing. Indeed, the Anglo-German sociologist Norbert Elias argued that modern sport emerged from the moment in the late eighteenth century when Britain allowed alternation of government according to the rules of a game. That was when the idea of political life as a game of the ins and outs took hold. If you lost a game you lived to play another day; and so on for as long as you wished to play. What the game is about, the serious business that the players ignore is, alas secondary to the game itself and the pleasures of apparently winning.

Comments powered by CComment