- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Custom Article Title: Patrick McCaughey reviews 'Reason and Lovelessness: Essays, encounters, reviews 1980–2017' by Barry Hill

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Barry Hill’s collection of essays from the last four decades is commanding and impressive. Few could match his range of subjects: from Tagore to John Berger, Lucian Freud to Christina Stead – all, for the most part, carried off with aplomb. He catches the ‘raw’ edge of Freud’s studio – ‘worksite’ as Hill calls it ...

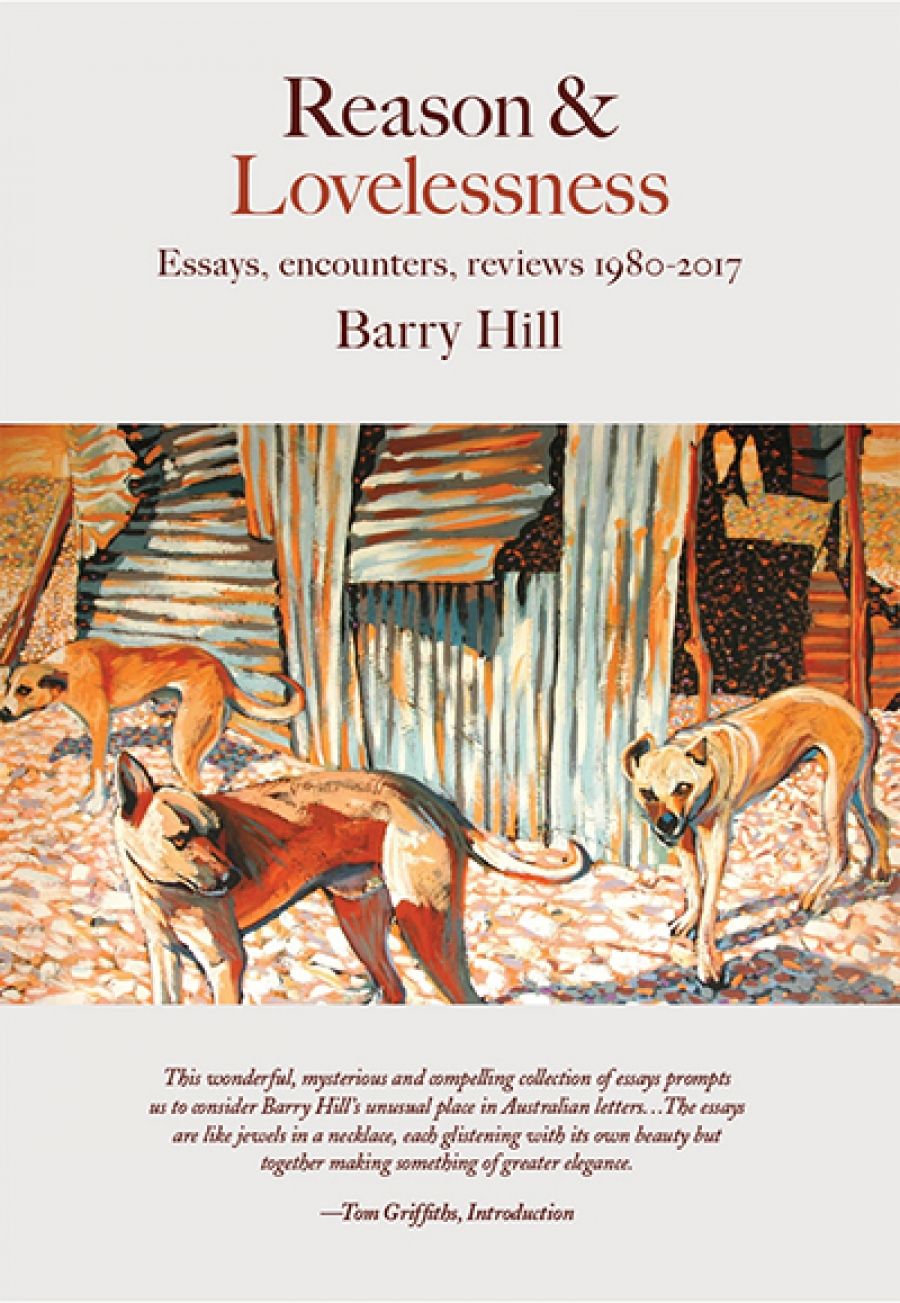

- Book 1 Title: Reason and Lovelessness

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays, encounters, reviews 1980–2017

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.95 pb, 511 pp, 9781925377262

The ballast of this heterogeneous collection lies in the section, Inland. Central Australia is the arena of the never-to-be-reconciled tension and relationship of black and white. Tellingly, it is the ground of Hill’s being as poet and novelist, historian and critic. In a mildly tendentious essay on Baldwin Spencer’s Through Larapinta Land (1896), Hill disputes John Mulvaney’s claim that Spencer’s narration of the Horn Expedition ‘ranks among the few distinguished works of literature in the history of Australian exploration’. Hill, however, ends the piece with the startling and moving, assertion that ‘central Australia [is] at the living heart of our culture’; the place where ‘our connectedness with all living things and places’ is made manifest.

If you fall short of such a recognition, as Hill believes Baldwin Spencer does, you are seriously at fault. Spencer never mastered Aboriginal languages and, according to Hill, could not distinguish between the tribes. Nevertheless, Spencer’s collection of Aboriginal bark paintings remains one of the cornerstones in the recognition of Aboriginal art as art, not just ethnographic specimens.

In a succession of essays on W.E.H. Stanner, T.G.H. Strehlow, and John Wolseley, among others, Hill outlines his argument of the Centre as anvil and axle of the Australian cultural experience. Strehlow’s Songs of Central Australia (1971) is accorded an honoured place in the recovery of Aboriginal culture for white Australia. No doubt his contrarian reputation as ‘a cranky, mysterious anthropologist’ appealed to Hill. But none shall ’scape whipping. Hill regrets that Strehlow’s version of the Songs ‘[sounds] like Rossetti’ – whether Dante Gabriel or Christina, he does not specify. Heinrich Heine, so familiar to the German Strehlow, might be closer to the mark. Although Hill hails him as ‘Strehlow the Magnificent’, the contrariness cannot be entirely subdued. When Strehlow seeks to place the Songs of the Centre on the same shelf as other collections of ancient poetry, Hebrew or Greek, Old Norse or Old English, Hill finds it ‘laudable enough’, then expostulates: ‘but only after one has repressed the question: why shouldn’t the Australian poetry be on the world map, how could it be anywhere else?’

Barry HillThe biographical essay on John Wolseley, ‘Holding Landscape’, is one of the finest in the collection – intimate, affectionate, uncensorious. Wolseley was born into the Somerset squirearchy on a 300-acre estate, ‘Nettlecombe’. He was the eldest son but his childhood was blighted and tragic. His mother committed suicide when he was a child. His father drank and had to be disestablished from the estate before it went under. ‘My greatest comfort was in the countryside itself, in the valleys and bosomy hills of Nettlecombe.’ Through the agency of Samuel Palmer, the visionary romantic painter and friend of William Blake, and his twentieth-century follower Graham Sutherland, Wolseley found his voice as an artist. Burdened by the responsibilities of running the estate, Wolseley came to Australia in 1976. He took to the landscape immediately: first, the dramatic littoral of the Great Ocean Road; then the dense bush of the Heartbreak Hills in Gippsland. They gave rise to his inspired reportage of the landscape. The paintings were like explorers’ sketches, maps, and diaries. Inevitably, Wolseley ventured into the interior where his engagement was so intense and so sustained that he was adopted by an Aboriginal tribe. As with Barry Hill, so with John Wolseley, ‘Central Australia is at the living heart’ of his enterprise and culture.

Barry HillThe biographical essay on John Wolseley, ‘Holding Landscape’, is one of the finest in the collection – intimate, affectionate, uncensorious. Wolseley was born into the Somerset squirearchy on a 300-acre estate, ‘Nettlecombe’. He was the eldest son but his childhood was blighted and tragic. His mother committed suicide when he was a child. His father drank and had to be disestablished from the estate before it went under. ‘My greatest comfort was in the countryside itself, in the valleys and bosomy hills of Nettlecombe.’ Through the agency of Samuel Palmer, the visionary romantic painter and friend of William Blake, and his twentieth-century follower Graham Sutherland, Wolseley found his voice as an artist. Burdened by the responsibilities of running the estate, Wolseley came to Australia in 1976. He took to the landscape immediately: first, the dramatic littoral of the Great Ocean Road; then the dense bush of the Heartbreak Hills in Gippsland. They gave rise to his inspired reportage of the landscape. The paintings were like explorers’ sketches, maps, and diaries. Inevitably, Wolseley ventured into the interior where his engagement was so intense and so sustained that he was adopted by an Aboriginal tribe. As with Barry Hill, so with John Wolseley, ‘Central Australia is at the living heart’ of his enterprise and culture.

Perceptive and stirring as these essays from the interior are, Hill is equally impressive when he turns to George Orwell, the Ezra Pound of Cathay, and the poetry of D.H. Lawrence. The Orwell essay takes the honours, however, and would make a good introduction to any anthology of his writings. To the conventional wisdom of the transparent prose mirroring Orwell’s moral clarity, ‘clear of cant’, Hill connects it to his contemporaries, to William Empson’s lexical literary criticism. A.J. Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic (1936), and, more surprisingly, to D.W. Winnicott, practising what Hill calls ‘a very English version of psychoanalysis’.

In a book of such high seriousness, one is all the more surprised by the lapses in critical language. We are treated to the banality ‘treasure trove’ more than once, and in a remarkable historical essay on the escaped convict William Buckley, we are told that ‘in our hearts of hearts we know how the Buckley story sits’ – hardly a precise location. His admiration for Tagore passeth all understanding, and his strident self-dramatisation that he once travelled on ‘the albatross of an Australian passport’ puzzles the will.

Comments powered by CComment