- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

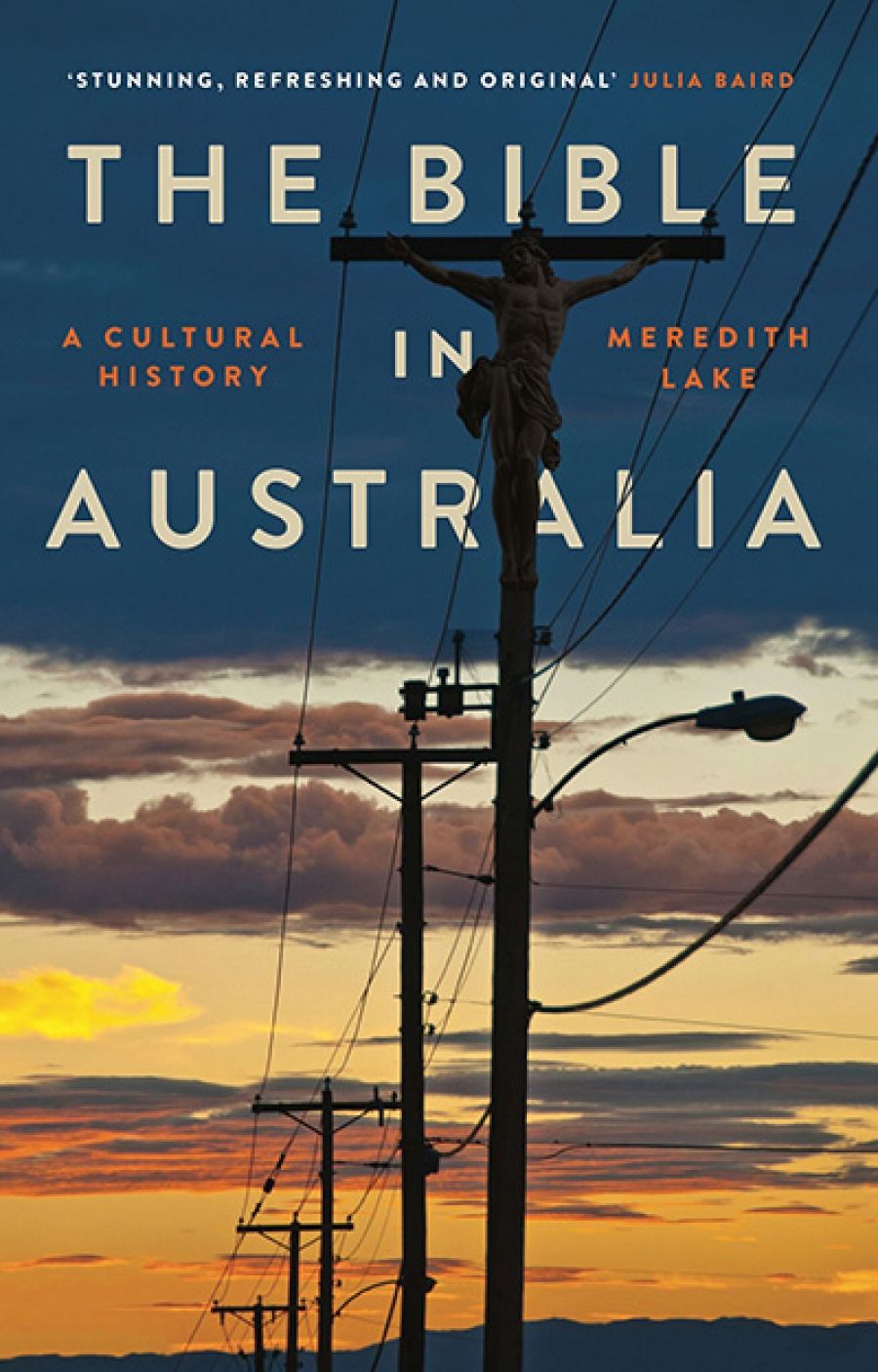

- Custom Article Title: Alan Atkinson reviews 'The Bible in Australia: A cultural history' by Meredith Lake

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Bible in Australia is an unpretentious title for a remarkable book, and yet it is accurate enough. The Bible has been an ever-present aspect of life in Australia for 230 years, but no one has ever thought through its profound importance before. By starting her argument in a place both strange and obvious, Meredith ...

- Book 1 Title: The Bible in Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: A cultural history

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 439 pp, 9781742235714

During the last few decades there have been many indications that First Nation stories might somehow do the same. This was the implication, say, of Bruce Chatwin’s Songlines (1987) and Barry Hill’s Broken Song (2002), and a globally significant outpouring of new Indigenous painting, song, and dance offers such hope. A title such as The Bible in Australia sounds retro, but this book takes the effort further forward, which explains its deep importance now.

Early on, in explaining the Australian impact of the Bible, Lake distinguishes between the ‘globalising Bible’, the ‘cultural Bible’, and the ‘theological Bible’. In fact, these categories overlap a good deal, especially ‘globalising’ and ‘theological’, which merge especially on issues of ethics and sanctity. From generation to generation, ethical issues are well explored, and so is the idea of the Bible as ‘a treasure trove of cultural riches’. Theology, on the other hand, and the Bible’s impact on the Australian intellectual world view, is not one of the book’s particular strengths.

Lake argues that for most of the period of non-Indigenous settlement the Bible has shaped and to some extent driven the Australian experience. So she says, in dealing with the early colonial period: ‘The Bible nourished notions of place and providence that went to the heart of the emotional and psychological history of white settlement in Australia.’ God’s Word, so called, affected common imagination not just directly but also indirectly, through various winding ways and through all degrees of Christian piety. A longer book might have been more precise as to just how this happened, detailing not just result but also process, including the ways in which other cultural traditions were variously interwoven with biblical understanding. With more room, finer distinctions might have been drawn between the influence of the Bible, the influence of Christianity generally and the influence of religion and spirituality in a generic sense. But then, who reads longer books than this, especially on what seems at first to be a specialist topic?

The middle decades of the nineteenth century Lake calls Australia’s ‘great age of the Bible’, all the more important because those who grew up at that time were leaders at all levels during the period of Federation and World War I. This is where Lake’s account works most incisively as a recasting of the national story. By the 1860s, high standards of literacy and a surge in print publication coincided with a remarkable degree of shared religiosity, and as a result by the 1880s, when the question of Federation began to engage the public imagination, ‘levels of biblical literacy were at an historic high’ in Australia. ‘The Bible was a shared point of reference, a part of common life … It readily produced transformative engagement with society and its members.’ In other words, the Bible shaped both questions and answers about Federation. The Old Testament created a sense of Providential direction. The New Testament determined moral purpose, clarifying the ways in which constitutional change might reinforce social justice and ‘the good society’.

Bible found in the Australian bushranger Dan Morgan's camp on 15 September 1863, published London, 1857 (Wikimedia Commons)

Bible found in the Australian bushranger Dan Morgan's camp on 15 September 1863, published London, 1857 (Wikimedia Commons)

So too, ‘[t]he Bible was crucial to the ways Australians experienced the First World War’. It was ‘part of the material, emotional and intellectual lives of many service men and women’ and it ‘informed the ways the legacies of the war played out in Australian culture’, especially in the ceremonies of remembrance. Again, biblical understanding created a pathway through common imagination along which national understanding might travel.

What explains the strengths and limitations of the Bible’s impact, in Australia and elsewhere? What puts the Bible in a particular class of literature, almost in a class of its own? In the end, Lake does not offer an explanation. The American literary critic Harold Bloom, on the other hand, points to the Bible’s literary power, which, as with Shakespeare, Bloom says, seems superhuman because abnormally and endlessly rich. There is a level of human creativity or mental reach, from Homer to Stephen Hawking, which takes the bulk of humanity out of its depth. In pre-modern terms, such work seems to deserve reverence, even worship. Lake’s book illustrates the process well. What Ward saw as scepticism among Australians, may have been more like taciturn bafflement. And then, on the contrary, we have Helen Garner’s response to a first reading, as quoted by Lake: ‘there were passages … that made my hair stand on end – with horror, bliss, and technical awe’.

Again, Lake’s book raises more questions than it can reasonably answer. But surely we do need a larger discussion about the way in which a mere piece of writing enters into the realm of the apparently supernatural. That in turn would depend on our willingness to imagine the supernatural, which is now rather hard to do – a loss of competence as tragic, surely, as the loss of a great language.

Meredith LakeShakespeare’s plays are performed everywhere. Similarly, one of the particular strengths of The Bible in Australia is the open-minded way in which it deals with the uptake of the Bible for various reasons among a wide range of people, not all of them by any means church-governed. Weaving right through The Bible in Australia are questions about the impact of the Bible on Indigenous peoples, and their impact on it. Lake begins with Boorong, a girl who lived with Mary Johnson, wife of the first chaplain, until she went back to nakedness and the bush. Later, her son, Dickey Bennelong, was to be a fervent preacher of Bible lessons. Towards the end we hear of activists (Don Brady, Charles Harris, David Kirk, Anne Pattel-Gray, and others) who used the Bible to shape an Australian version of Black liberation theology in the 1970s, and others (Jarinyanu David Downs, Shirley Purdie, Gurrumul Yunupingu) who made biblical reinterpretations of Indigenous culture, in a merging of legends. Eddie Mabo was likened to Moses among his own people.

Meredith LakeShakespeare’s plays are performed everywhere. Similarly, one of the particular strengths of The Bible in Australia is the open-minded way in which it deals with the uptake of the Bible for various reasons among a wide range of people, not all of them by any means church-governed. Weaving right through The Bible in Australia are questions about the impact of the Bible on Indigenous peoples, and their impact on it. Lake begins with Boorong, a girl who lived with Mary Johnson, wife of the first chaplain, until she went back to nakedness and the bush. Later, her son, Dickey Bennelong, was to be a fervent preacher of Bible lessons. Towards the end we hear of activists (Don Brady, Charles Harris, David Kirk, Anne Pattel-Gray, and others) who used the Bible to shape an Australian version of Black liberation theology in the 1970s, and others (Jarinyanu David Downs, Shirley Purdie, Gurrumul Yunupingu) who made biblical reinterpretations of Indigenous culture, in a merging of legends. Eddie Mabo was likened to Moses among his own people.

The liberating and enlarging power of the Bible is central to Lake’s argument. She writes also of Australian feminist theologians, such as Marie Tulip, who saw it also in that light. The collective character that Ward’s legend attributed to Australians was slow moving, slow talking, and largely reactive. The Anzac story, which overlaps with Ward’s legend, adds to that traits of extreme courage and stoicism. The legend outlined by Lake suggests a national character larger than both and, potentially at least, more pro- active and less predictable. As she shows very well, there is room in her legend for endless variety of usage and interpretation.

The last chapter includes reflections on the Bible in the twenty-first century. Among other things, the digitised, searchable Bible promises new methods of biblical criticism and interpretation. The fifteenth-century printing of the Bible brought about the Protestant Reformation, but it is too soon to tell if these new means of access will have an equivalent impact. Implicit in the end is a conviction that even such mighty changes can hardly exhaust the Bible’s power.

Comments powered by CComment