- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Joan Fleming reviews 'Domestic Interior' by Fiona Wright and 'The Tiny Museums' by Carolyn Abbs

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The classic lyric preoccupation with interiority, and how internal life touches and changes the outside world, finds expression in two recent collections of poetry: Fiona Wright’s ...

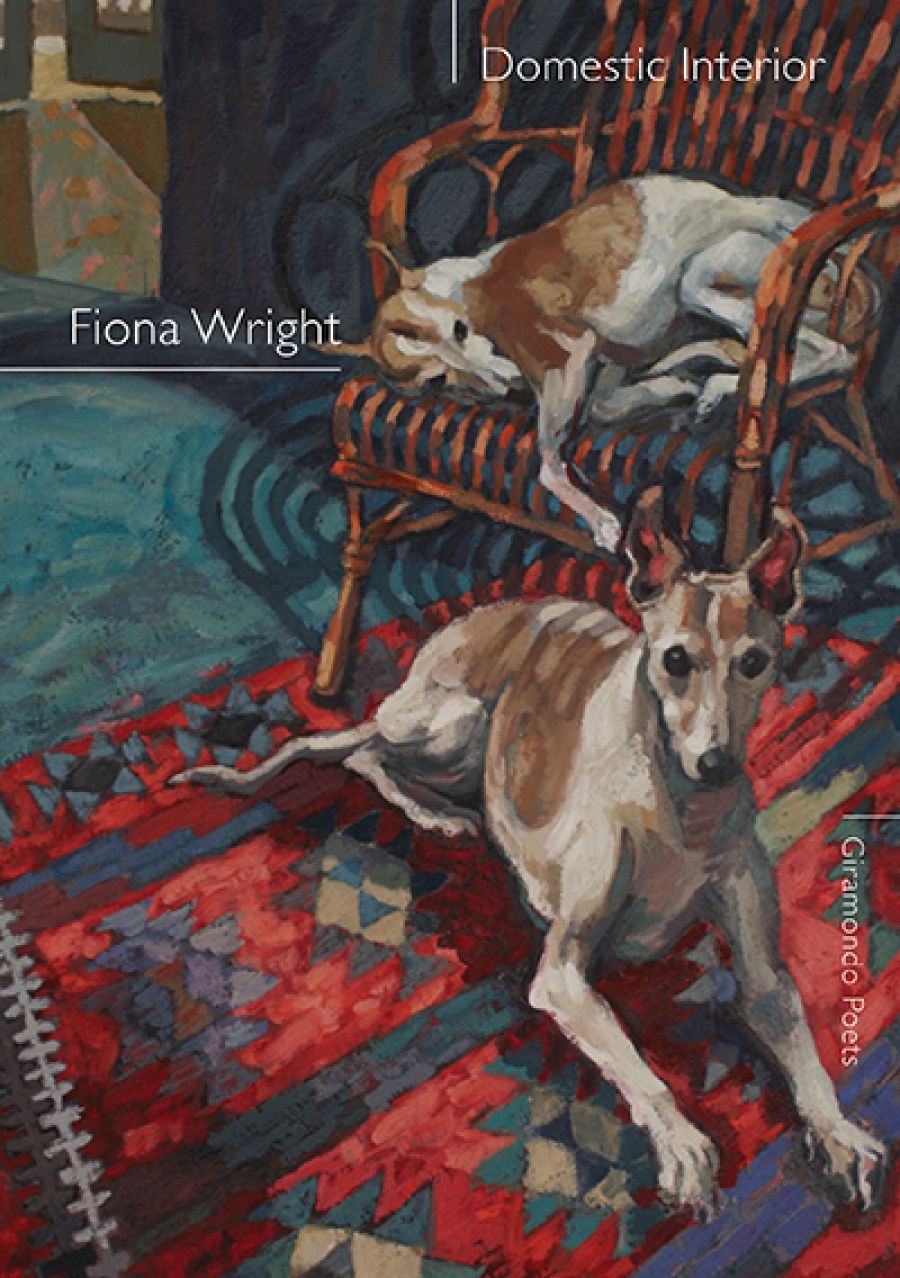

- Book 1 Title: Domestic Interior

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 93 pp, 9781925336566

- Book 2 Title: The Tiny Museums

- Book 2 Biblio: UWAP Poetry, $22.99 pb, 120 pp, 9781742589541

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): ABR_Online_2018/April_2018/The Tiny Museums.jpg

Section titles are deceptively direct. ‘A Crack in the Skin: On Illness’ promises a coherent theme, but leaves the reader to divine the circumstances of a body under threat, growing ‘numb’, ‘empty’, bruised, ‘crushed’, and ‘shivering’. Wright writes, ‘It thinks in me, / this shadow’, and later wonders, ‘How did it help us, the sorrow in our marrow?’. Monsters lurk in the ordinary corners of the suburban home, its medicine cabinets and fridges. Menace is penetratingly everywhere. The speaker of the title poem has had to learn ‘to walk bruiseless / to the bathroom in the dark’. Mood is undeniably strong, but is mood enough? Without the context of this sadness, so insisted upon, does it read as merely ennui?

An extra-textual knowledge of Wright’s battle with anorexia, and her time in institutional rehabilitation, brings out further dimensions to the poems. The collection is punctuated by a series of ‘conversation poems’. These are lively, sometimes wretched, and often very funny transcriptions of overheard speech. The ‘Tupperware Sonnets’ are particularly diverting: ‘Don’t they go yuck? I mean, I hate using plastic, but always worry, won’t their sandwiches go yuck? They don’t eat their sandwiches if they go yuck ...’ Wright says the conversation poems are among her favourite in the collection, perhaps because they constitute a break in voice – a break from the poet ‘stewing in [her] own sour air’, as Sylvia Plath’s character Esther put it in The Bell Jar. These instances of comic relief are a respite from the pervasive states of anxiety and unsettlement that run like an underground river beneath the terrain of these poems.

Carolyn Abbs’s collection is more explicitly autobiographical than Wright’s. It follows the arc of a classic memoir, painting scenes of childhood memories, investigating family trauma and secrets, and staging the adult coming to terms with the imprint of the past on the present.

The collection’s best poems are charged with narrative intensity and family drama. The speaker revisits a childhood home where now-unimagin able traumas took place; she remembers a sister with tuberculosis being threatened with quarantine.

The Tiny Museums came highly commended in the 2016 Dorothy Hewett Award for an Unpublished Manuscript. The judges praised the collection as a book that telescopes time: ‘Abbs’ poems … live in the gap between deep time and now … Abbs deftly creates the world of her book through a phenomenological approach. Elegant layers of textures, colours, sounds and movement invite the reader into an experiential sense of this trench between the past and the present.’ A pair of poems at the heart of this book, for example, manage this trick with great skill. The slide into memory, and back into the present, is absolutely liquid:

Outside a shut door I hear a doctor murmur sanatorium

Our mother’s nurse-voice No!

We search through blindness my ring clinks a chrome railing

Old people in parked cars peer through half moons of windscreens

sip thermos tea wait for mist to lift

hush of the shore sanatorium sanatorium No!

The poem on the facing page, titled ‘The Shrine’, similarly glides the speaker and her sister between temporal realities. In some intimately known woods, the speaker sees a girl in a red dress: ‘I can’t tell if it is our mother as a child / or if it is me running towards her.’ This utterly subjective declaration of impossible fact is beautifully managed. It attests to the realness of memory as it lives in the waking present.

However, the adroitness of these examples is not a consistent feature of the collection. Many scene-poems – a grandmother’s dressing table, a father polishing shoes – fail to vibrate without the dramatic charge of a narrative. Abbs’s unpretentious, quiet style has been praised as ‘unsentimental’, but despite the occasional fine turn of phrase – ‘there was a tavern of voices outside’ – the objects described do not seem to hold much more than the plain visual fact of themselves. Epigraphs to the poems – like a line from Simon Armitage: ‘Poetry attempts a dialogue with the departed’ – are overly directional. A writerly tic sees the regular omission of articles, adverbs, and pronouns in otherwise uninflected speech. This does not equal poetic compression.

At 120 pages, the collection is uneven and over-long. This late début exhibits a consistent voice, though there are promising moments of formal experimentation. ‘Piece of Lace’, a prose poem, has staccato punctuation and a rush of single syllable words that aptly deliver an unsettling menace. Such menace is handled less successfully in other poems, where safe rhythms and uncharged language make an ending such as ‘You will never escape / the stench of mud and blood’ feel unearned. A stronger editorial hand might have helped shape Abbs’s talent into a more consistently satisfying collection.

Comments powered by CComment