- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the list of life’s most stressful events, family breakups and moving home are way up there in the top ten, and one often follows the other, compounding the trauma. This is the situation for eleven-year-old Rain in Catherine Bateson’s Rain May and Captain Daniel, when her mother, Maggie, sells their inner-city house in the aftermath of divorce. They head for the country to turn Grandma’s deceased estate into a dream home. Maggie’s hopes are higher than her daughter’s: she foresees serenity, harmony, and self-sufficiency; Rain expects ‘Boringsville’.

- Book 1 Title: Rain May and Captain Daniel

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $14.95 pb, 138 pp

- Book 2 Title: Too Flash

- Book 2 Biblio: Jukurrpa Books, $17.95 pb, 207 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Jul_2021/51S4824G73L.jpg

Their new life gets off to a shaky start when they discover possums in the roof, mouse droppings in the combustion stove, and that the local shops shut at five o’clock. Salvation for Rain comes in the unexpected form of a precocious young neighbour, Daniel, a fervent Trekkie and an outcast at school. Against all odds they become friends, but Daniel knows that once term starts the exotically named new arrival will be ‘swept up by the tutu and jodphur girls’ and that he will be sidelined again. Rain’s tense access weekends with her father and his shopaholic younger girlfriend leave her, too, feeling excluded. In the meantime, compensations begin to reveal themselves in the country: friendly neighbours, platypuses in the creek, a puppy, more time with her mother.

Giving a fresh kick to this Sea Change narrative are the funny and often poignant extracts from Daniel’s Captain’s Log in full Trekkie mode – the new neighbours on ‘Planet 7’ are ‘colonisers’, his parents are the Counsellor and the Doctor – in addition to Maggie and Rain’s little ‘fridge poems’ that are scattered throughout and that complement the story. (Bateson’s previous titles include two collections of poetry and two Young Adult verse novels.) Bateson is adept at showing the pain of divided loyalties and how children of separated parents learn to filter the information they give to each. She is also on target with her themes of friendship and popularity, so important to this pre-pubescent age group. The ending is not quite as good as the beginning, involving as it does a tragic illness and a sudden dash to hospital in order to create an emotional crisis to which everybody can react admirably. However, the target readership (late primary) will love it. What I admired was the lively writing and good humour, the general absence of sentimentality, and the engaging Captain Daniel.

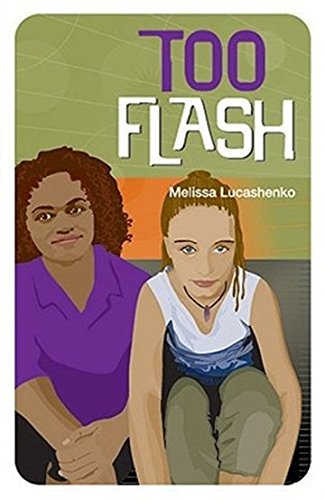

Far from wanting to escape executive stress, Anna, the single mother in Melissa Lucashenko’s Too Flash, welcomes new responsibilities as she climbs the bureaucratic ladder. That this involves a move south to Brisbane doesn’t go down well with her fifteen-year-old daughter Zo, particularly as she has to leave behind the Fefitas, a large and exuberant Tongan clan that has become something of a substitute family to her. Zo, more white than black except in skin colour, never knew her long-dead father, a Cape Murri, and longs for closer ties with her Aboriginal relatives, despite the fear that they might call her ‘halfcaste, yellafella, with no lingo, no culture’.

What Zo lacks in the way of family is compensated for by the affluent lifestyle and bright future she faces thanks to her mother’s job and emphasis on education. In Brisbane she meets Missy, whose chaotic Koori household overflows with extended family and always finds money in short supply. They become friends and Zo discovers what life’s like when you have cops at the door, no food in the fridge, and mildew in the ceilings, while the cheeky, street-smart Missy is not slow to take advantage of Zo’s material benefits. Despite a few prickles, they help each other deal with sexual harassment and racism in various guises, but the difference in their backgrounds eventually drives a wedge between them. Missy lashes out at Zo:

I’m telling ya, you flash blacks got no fucken idea how things really are for Koories … you live in ya uptown dream world with ya white mum, and her good job and ya flash car that starts every time, and all ya bills get paid on time and ya don’t feel sick when ya think about the next lot of bills … and nothing bad ever happens to ya … Money talks and bullshit walks in this world.

Missy sees money as the determining factor, but Lucashenko’s upfront message is that education is the key to advancement. Zo’s daydream is to be a rock singer (once she loses fifty kilos), but, by the end of the book, university and a scholarship to the USA figure in her career plans, while Missy has quit school and found a job ‘flogging teak entertainment units to yuppie brides’, as Zo puts it. The pejorative judgment is only partly softened by the ‘even though we’re different, we can still be friends’ message on the final page.

Zo is an engaging heroine in a novel rich in lively, well-developed characters, and strong female role models: Anna and her departmental head, Terri; Missy’s Aunt Gill who has put herself through TAFE and is researching native title; Ms Levy, the principal with the spiky hair and a reconciliation poster on her office wall; most vividly, the two wise Aboriginal aunties who drag a screaming Zo, Missy and a few other recalcitrants to ‘Kulcha Kamp’ for a spot of bonding in the bush. The humour and energy of the narrative never flag, but these particular chapters are the high point. The television series Survivor pales in comparison.

Lisa Reidy’s striking cover image of the two girls, and the narrative style that mimics colloquial indigenous speech, make its target readership clear. (The Alice Springs-based IAD Press is the publishing arm of the Institute for Aboriginal Development.) Girls of a similar age and background to Zo and Missy will take this book to their hearts, but it’s sure to be enjoyed and welcomed by a much wider readership. Aboriginal words and references abound, but the text is self-explanatory: ‘“Yugam bungoo here,” said Trey mournfully, pulling his pockets inside out to prove it. Missy found two dollars sixty, and Zo chucked in the rest.’

Related largely through the voice and viewpoint of Zo (the occasional lapses into adult perspectives seem unnecessary), and with plenty of musical references, this book will sound terrific on audio. It tackles important and realistic issues that will be familiar to many young indigenous readers, and offers an insider’s perspective on others. It does so without being didactic, moralistic, or provocative, but with empathy, good humour, and a refreshing absence of political correctness. I hope Lucashenko will write again about Zo.

Comments powered by CComment