- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Slap in the Face from the Border

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At first glance this book looks like a quickie bashed out to take advantage of the looming war in Iraq and to cash in on the coincidence that the author – taking a break from his day job covering wars for the Sydney Morning Herald – happened to be in New York when the towers came down. But to see it in this light would be a disservice. What Paul McGeough has done is to draw on his reporting from Afghanistan, New York, Iraq, Israel, and the occupied territories, in order to give some coherence to the events of the so-called ‘War on Terror’. What we have ended up with is actually a very good rundown of the pre-existing conditions, conflicts and events of the past year and a half in disparate conflict zones. But for their being woven together by the common thread of the US reaction to 9/11, they probably would not have got into print.

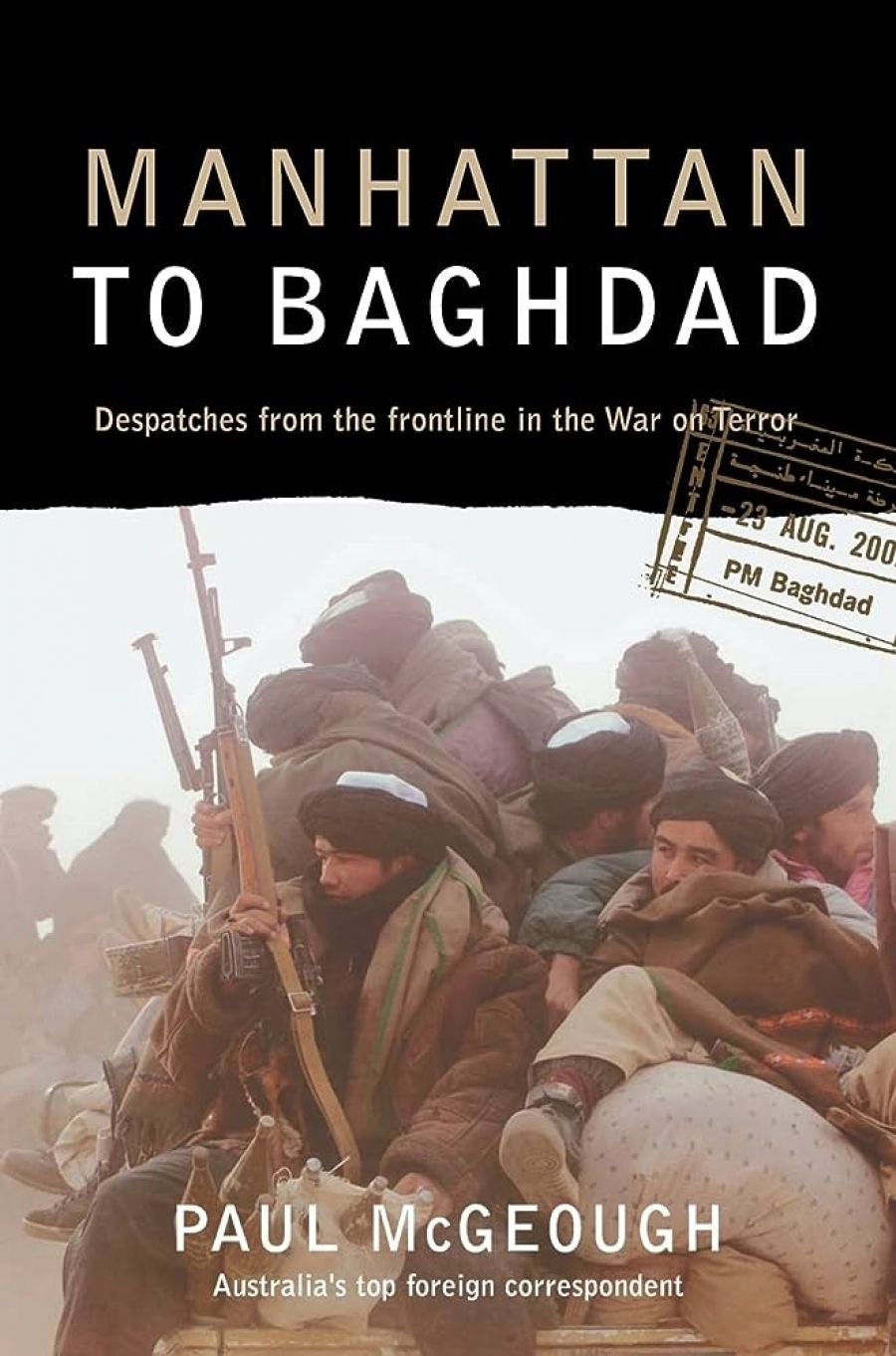

- Book 1 Title: Manhattan to Baghdad

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $29.95 pb, 298 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In Australia ‘people smuggler’ was a loaded term but in the refugee camps it merely equated with the Australian concept of ‘travel agent’; and as far as the administrations of Islamabad and Tehran were concerned, people smuggling was a victimless crime that was way, way down on the list of priorities in a part of the world where ‘desperation’ was about something a lot more serious than which team would win the footy on the weekend.

McGeough records the dire conditions faced by refugees and the frank comments of a UN worker in the camps, who says, apropos Howard’s refugee policy: ‘If I was an Afghan, I wouldn’t want to live in Afghanistan. I’d pull every illegal trick I could to get my family out of this awful place.’ Such straight, basic reporting is needed to open the eyes of the Australian public to what motivates ‘queue jumpers’ to take such risks to get here.

Next McGeough covers the events of 9/11 in Manhattan. He can’t resist telling the reader several times that he has just come from Afghanistan and that the events are connected. He retells the familiar but nonetheless epic story of that day in New York, before heading back to Central Asia to follow the US response attack on Afghanistan. In Uzbekistan, as he waits to get into Afghanistan, we are given the background on the plight of opponents of that country’s authoritarian regime, which is temporarily an ally of the United States for the sole reason that the United States needs its bases to attack Afghanistan. It is one of the ironies of this book that the most valuable material is not directly related to the so-called US war on terror but to those pre-existing conflicts and conditions that the US involvement now brings into the media spotlight.

The hardships of life in Afghanistan with the Northern Alliance, and the difficulties of reporting from such a remote place, are recounted along with some revealing detail about just how well supported a correspondent like McGeough is in the field. He talks of calling his GP in Double Bay on the company satellite phone because he suspects he may have an upset stomach. The deaths of three colleagues in a Taliban ambush is soberly recounted and highlights the risks in this kind of journalism and how easily a manageable situation can become a dangerous one.

Reporting the wave of suicide bomb attacks and the Israeli counter-offensive in Israel and the occupied territories, McGeough delivers some of the best material in the book. But, as one of the victims of the Matza restaurant bombing in Haifa says:

They say the Arabs are crazy but it’s not true. It’s someone who saw the same pain that I saw today, and he did it out of what he saw. They also feel pain. Those who blow themselves up are not terrorists; they are soldiers.

The Arab-Israeli conflict is not part of the war on terror; identifying it as such only plays into the hands of certain politicians. McGeough’s account of the aftermath of the Israeli attack on the Jenin refugee camp describes in vivid detail the destruction wrought by Israeli forces. It also sheds light on why this cycle of conflict has continued from 1948 until now. But this has nothing to do with planes hitting buildings in Manhattan, and it is misleading to link the two, especially if it is only to add an action-packed chapter to your book.

McGeough makes the distinction and his analysis clear in the final chapters on Iraq. As well as detail about dealing with the authorities in Baghdad, we get the frank judgment that countries such as Indonesia, Chechnya, and Palestine are more likely to be breeding grounds for terrorists than Iraq. His last line rings true: ‘But George W. Bush was determined to march on Baghdad. Somehow the president was in the wrong place, fighting the wrong war.’ And somehow this book is not really about the war on terror. It is about what Paul McGeough has been doing since it began, whilst he finished his morning coffee one bright September morning in Manhattan.

Comments powered by CComment