- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Dredging it up

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

According to Andrew O’Hagan, writing in a recent London Review of Books: ‘If you want to be somebody nowadays, you’d better start by getting in touch with your inner nobody, because nobody likes a somebody who can’t prove they’ve been nobody all along.’ The journey from Nobody-hood to Somebody-hood is central to June Dally-Watkins’s recent autobiography. Indeed, O’Hagan’s pithy insight could almost have been the Sydney socialite and queen of etiquette’s mantra.

- Book 1 Title: The Secrets Behind My Smile

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $39.95 hb, 280 pp

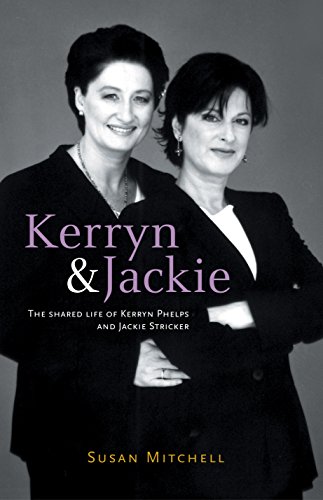

- Book 2 Title: Kerryn and Jackie

- Book 2 Subtitle: The shared life of Kerryn Phelps and Jackie Stricker

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $39.95 hb, 233 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Unfortunately for Dally-Watkins’s sales, however, the author’s experience of being illegitimate is unlikely to impress readers accustomed to tales about Billy Connolly’s childhood abuse or Geri Halliwell’s eating disorder. The difficulties Dally-Watkins faced as a fatherless girl in an Australian country town in the 1930s should not be underestimated. Nevertheless, and despite the reality of this hardship, this experience has little resonance in an era of single mothers. In a cultural context that associates good, or at least entertaining, writing with the self-revelations of the most traumatic or abject subjects, Dally-Watkins’s ‘heartache’ hardly rates.

Moreover, and perhaps more regrettably, the author demonstrates little insight into her suffering. Indeed, in the moments when this threatens to become most interesting, she reverts either to coy admissions (for instance, ‘I had a little post-natal depression’) or a neat narrative that forecloses the possibility of more meaningful self-investigation. This tendency is abundantly clear when, at the end of the book, after talking about the depression that led her to think that ‘life wasn’t worth living’, Dally-Watkins writes: ‘At least I know now that I’m resilient enough to keep smiling.’ Reflecting Dally-Watkins’s failure to deconstruct the very smile she purports to be looking behind, this bizarre statement encapsulates the somewhat paradoxical banality of a book that in the end reveals little other than O’Hagan’s claim that ‘celebrity means nothing now without the notion of suffering’.

This statement also helps to elucidate Susan Mitchell’s biography, Kerryn and Jackie: The shared life of Kerryn Phelps and Jackie Stricker. As a GP, television doctor, Women’s Weekly columnist and head of the Australian Medical Association, Phelps has attracted considerable attention for her lesbian relationship with Jackie Stricker.

When the couple were portrayed on Australian Story alongside Kerryn’s children, Jaime and Carl, they seemed to be a gay version of the Brady Bunch. Mitchell, however, exposes this image of happy functionality as a media myth. Surprisingly, she does this with the full support of Kerryn and Jackie, both of whom are quoted extensively in this ultimately sycophantic account of their lives. The book is clearly meant to be a testament to the couple’s apparent endurance against all odds, which include Phelps’s family. However, Mitchell’s bias is frustrating and raises questions not only about the other side of Kerryn and Jackie’s story, but also about the author’s refusal to employ any of the critical thinking tools of her journalistic trade. Mitchell portrays Phelps and Stricker as suffering for all kinds of reasons. Take Kerryn, for example. In the author’s hands, Phelps’s fairly average childhood becomes the original source of her pain, apparently evidenced in her ‘sad eyes’. Mitchell tells us that Kerryn felt ‘second-best’ once her brother, Peter, was born, and that, during adolescence, she suffered at the hands of a controlling and disciplinarian mother. Though completely unremarkable, both experiences are construed as things Phelps has ‘survived’ rather than simply lived. Consequently, they become crucial components in the narrative of suffering.

Mitchell’s capacity to incorporate all kinds of people and events into this tale of affliction is alarmingly obvious when she describes the difficulties Kerryn faced with her first child. ‘[Jaime] constantly demanded Kerryn’s attention and threw tantrums when she didn’t get her own way. Nothing, it seemed to Kerryn, was ever enough for Jaime.’ Given that Jaime was a toddler at the time and that Kerryn and Jaime (now aged nineteen) have been estranged for several years, this representation of Jaime as a child is particularly troubling.

Establishing the notion that Kerryn’s relationship with her daughter was doomed because of Jaime’s supposedly innate contrariness, Mitchell constructs Phelps as having not only survived her parents but also her ‘utterly perverse’ daughter. This portrayal of Jaime seems especially cruel, given her age. As such, it serves as evidence both of Mitchell’s partisanship and the lengths to which she is prepared to go in order to maintain her emphasis on the suffering of her Somebody subjects.

Certainly, Phelps’s broken relationships with her parents, daughter, and ex-husband suggest that her life is not entirely happy. Nevertheless, Mitchell’s simplistic portrayal of the Double Bay couple as the victims of just about everyone around them is not only not credible, but also irresponsible.

As ‘celebrities’, Kerryn and Jackie’s sufferings are supposed to embody the sufferings of us all, or at least all gay and lesbian lovers. In the end, however, Kerryn and Jackie seem less like martyrs than two rather difficult and self-important individuals with nice houses and flashy cars.

In contrast to Kerryn and Jackie, Rose Hancock Porteous is never portrayed as representative. Indeed, her ‘celebrity’ status depends precisely on the fact that she is not so. If Dally-Watkins and Kerryn and Jackie are supposed to represent us all, Hancock Porteous serves as a potent media symbol of all that we are not meant to be or become.

Perhaps more importantly – at least from a publishing perspective – Rose’s outrageous life makes perfect copy. In his ‘unauthorised biography’, journalist Robert Wainwright maximises this potential. Skilfully exploiting the interests of an already established audience – namely the readers of popular women’s magazines – he outlines all the gob-smacking details of the Filipina’s life and four marriages.

Predictably, Rose appears in a less than flattering light. Unlike in Dally-Watkins’s, there is plenty of sludge in Rose’s life to dredge up. Apart from snaring a ‘big fish’ by marrying the elderly millionaire Lang Hancock, Rose is a ‘former’ drug addict with a long and audacious career as a manipulative ‘sexpot’. Her repeated abandonment of her daughter, Johanna – who says that her mother slit her wrists in front of her when Johanna was a child – is presented as further evidence of her depravity. As if all this weren’t enough, there’s Rose’s fantastically tasteless splurges, including her gift to a 79-year-old Hancock of a life-sized mannequin of herself. Wainwright’s portrayal is more rounded and researched than Mitchell’s. For instance, as he comments in the ‘notes on sources’ section at the end of the book, he went to the Philippines to conduct interviews with various family members and friends, many of whom have quite different perspectives from Rose. Wainwright’s tendency to colour his tale with imagined scenarios and scenes is, however, lamentable. He remarks, for instance, that had Rose’s father been at his daughter’s wedding he ‘might have shrunk with embarrassment at the sound of the bridal march – “Suicide is Painless”’. Elsewhere, the author places himself inside the heads of his ‘characters’: for example, ‘Hancock’s mind raced’.

Reflecting the highly porous boundaries between biography and fiction, the book constitutes something of a rejoinder to Drusilla Modjeska’s recent celebration of fluidity and experimentalism in life-writing.

While Rose is compelling in the manner of Who Weekly, the book might have been genuinely meaty had Wainwright sought an answer to the question of Rose’s popularity among a scornful, but amused, Australian public. He comes close to this at times, acknowledging, for instance, Rose’s victory over Gina Rinehart in the battle for public sympathy. Unfortunately, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the author is more concerned with responding to, exploiting, and perpetuating the public’s fascination with Rose’s eccentricity than with analysing it.

In the end, it is Rose who gives us an insight into her popularity. Discussing her arrest for driving under the influence of drugs, Rose declared to a panting press throng: ‘People can look at my life and take lessons from it.’ While Dally-Watkins and Kerryn and Jackie are meant to represent us all, Rose’s statement reminds us that it is she who truly reflects how we want to see ourselves. Laughing at her outrageous antics, we define ourselves in opposition. Providing ‘lessons’ in how not to be, she allows the Nobodies of the world to feel successful and superior. By contrast, and despite their attempts to convince us of their suffering, June’s, Kerryn’s and Jackie’s lives do not speak to us – or allow us to construct ourselves – in the same way.

Comments powered by CComment