- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Memory's beautiful mariner

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Memory's beautiful mariner

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

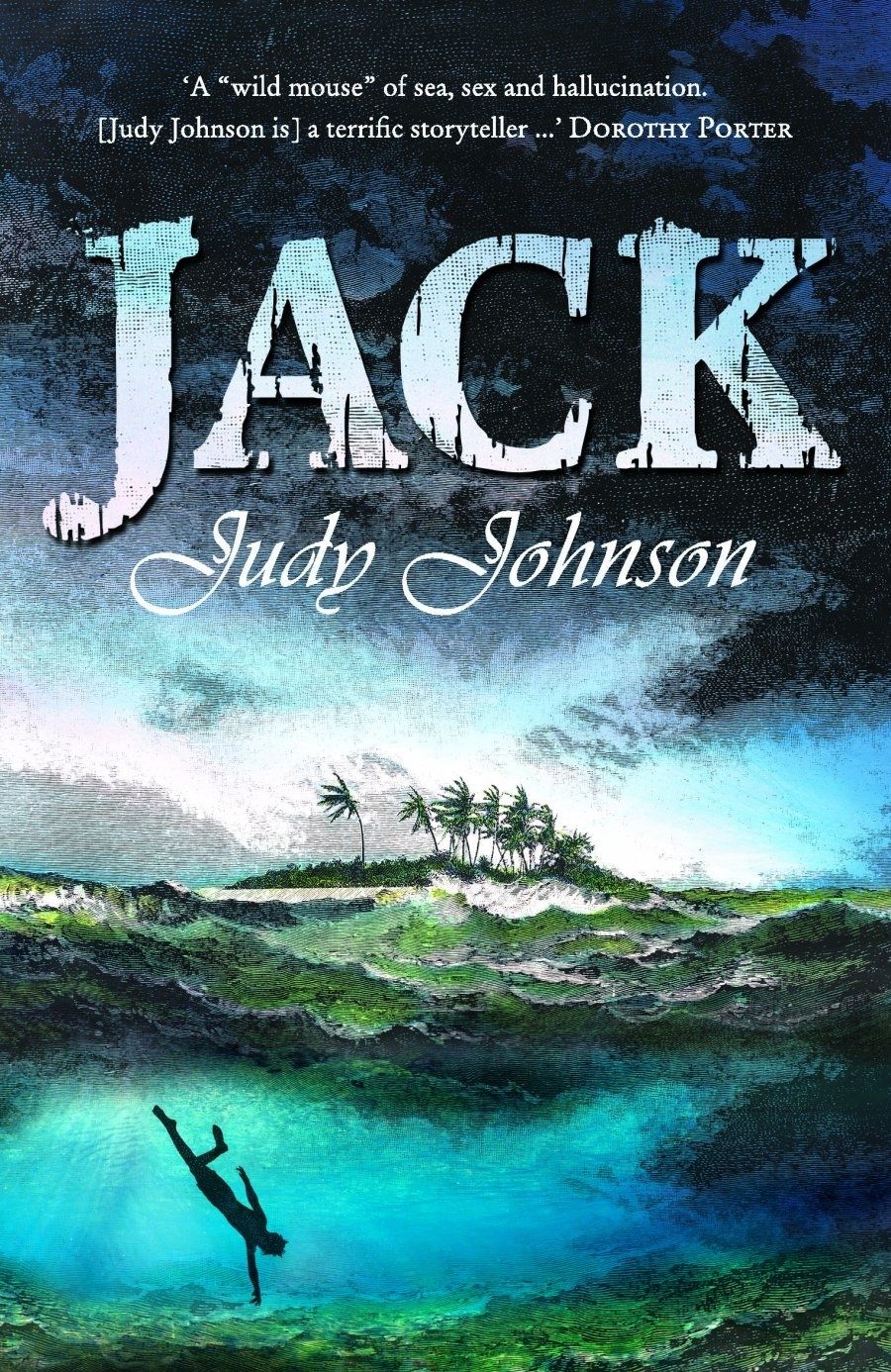

Narrative, historical narrative in particular, figures strongly in these recent books from Judy Johnson – one a new collection of poems, the other a welcome reissue of her verse novel. Jack was first published in 2006 by Pandanus, shortly before that imprint’s demise. It won the 2007 Victorian Premier’s Award for Poetry, and is republished now by Picador. With its lonely, embittered, one-eyed captain, its miscellany of onboard characters and Coral Sea setting, it is not without potentially cliched romantic elements – which the Picador cover, with its Blue Lagoon-like scene and blockbuster typeface, is happy to trade on. But Jack compels.

- Book 1 Title: Jack

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $24.95 pb, 295 pb, 9780330424226

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Navigation

- Book 2 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $19.95 pb, 88 pp, 9780734037565

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

On Thursday Island in 1938, Jack Falconer assembles a crew of Islander, Papuan, Japanese, Chines and Aboriginal men for his claustrophobic pearling lugger. As they move from one Torres Strait pearling ground to another, he antagonises the diver Takemoto, and makes sexually opportunistic overtures to the Islander Georgie. Manipulative and pugilistic, he holds forth with a perverse system of justice. Moreover, he is dogged by feelings of resentment, having lost an eye in a boyhood spat with his brother, then being denied the chance to fight in World War I. That same brother has drowned recently in an incident in which Jack is implicated. His wife also died in dubious circumstances.

One thinks here of another iconic sibling Jack of Australian fiction – that of George Johnston's My Brother Jack ( 1964). Jack Meredith is similarly deprived of the opportunity to fight in war, but whereas he upholds a sense of fairness that has some legitimate moral foundation, Jack Falconer appropriates a version of the Australian fair go to navigate a punitive and destructive passage. So it comes as no surprise, for example, that he chastises Takemoto for wanting to harvest all available pearl shell in disregard of what he claims is the Australian custom to leave some 'for the poor bastard / following behind'. It is clear that Jack's argument has more to do with harnessing cultural difference to a racist end than concern for the well-being Along of others.

Jack is, nevertheless, well read. Along with his bitterness, he carries with him the Bible, Shakespeare, Coleridge and Blake. But it quickly becomes clear that Jack long ago moved from Blakean Innocence to Experience. His deceased wife visits him in dreams. Early in the narrative, her visits are charged with eroticism, but as we learn more of Jack’s past and as his behaviour grows disturbing, her spectral appearances become the prickings of conscious.

Hauntings occur throughout. Jack’s skin itches ‘like the spectre / of all those fish I’ve caught / and wrenched open at the neck / come back to haunt me’. The memory of his dead brother, and the manner of his death, disturb him. Then there is the deep water of the working grounds themselves, at once a ‘Garden of Eden’ but also a place where one confronts oneself (underwater, Jack meets with a large groper missing an eye, and finds the resemblance to himself unflattering) and, almost literally, the ghosts of one’s past. Indeed, Takemoto believes Darnley Deeps, the site of the book’s climax, to be haunted.

Broken into short poems of mostly one or two pages each, Johnson employs a comparatively simple verse style, with occasional rhyme. While Jack's first-person vernacular lacks the tonal elan of her new book, the strong historical narrative provides for a memorable voyage.

In Navigation, we see the world at large – a world of temporal as well as spatial sprawl – brought to bear on the personal. This wider world impinges on, and through metaphor helps articulate, the minutiae of the everyday, as in the opening poem, ‘Archaeologist’:

and now it seems

We are left alone

with this

archaeologist’s brush,

magnifying glass,

and a disclaimer

we should have read

in the beginning –

Navigation is divided into four sections. The first, 'Ties', traverses family, relationships, death, and personal and wider histories. In 'Love Poem', the archaeologist is there again, watching 'from a shadowy corner of the room', and lending, within the parameters of the poem, a literal distance to even the most intimate moments – in this case the physical act of love. Of the poems negotiating death in this strong opening, 'The Owl and the Pussycat and the Dying' is a sad but not maudlin take on the nursery rhyme that effectively appropriates the charm and whimsy of the original, while in poems such as 'Cannas', the 'fibrous blood' of plant roots secrets its way through the body like a cancer, undoing it cell by cell. In other poems, it is childhood that is undone and reassembled by memory.

The next section, 'Whale', comprises two longer poems that evoke the history of whaling – pertinent at a time when Japanese whaling for 'scientific' purposes is again newsworthy. The first poem, 'Whale Songs', is a hymn of praise told from the perspective of the whale. It nevertheless draws from the (human) quotidian (as the whales dive, their tails hover 'like joke-shop rubber eyebrows') and the mythical (the whale song should smell 'faintly of lamb and / persimmons rained on by the evaporating mists of Atlantis). Quietly anti-whaling – ‘Let our skeletons remain unscribbled / by the terrible beauty of scrimshaw’ – this brilliant poem has one marvellous image tumbling after another, but never sells out to Nemoesque cuteness or the easy dramas of Sea World.

'A Whaler's Wife', the second poem in this section, recalls the narrative impetus of Jack. Johnson draws from historical research to tell of Ellen Scott, who in 1886 left from Albany for a whaling journey on the ship of her captain husband. Written in five parts, this longer poem is necessarily aware of its literary precedents. Scott is 'with child', which to the superstitious crew means luck, and Scott feels herself a 'resident albatross'. There is the iconic 'Captain with his looking glass', and when a whale is harpooned, it is a 'Lilliputed Gulliver'. Ellen Scott's concord with the whale is explicit, and as the men dismember the 'slippery colossus', Scott's 'scrolled fruit' of unborn child 'unravels / on a river of blood'. This affecting poem, like so many in this collection, deftly juxtaposes scrimshawlike detail with an oceanic vastness.

The final two sections of the book are 'Reason' and 'Evanescence'. The former deals variously with the logic of the natural world ('Prisoner's Dilemma'), function ('Three Tools' and 'Silence') and justification ('Exhibit' and a sequence, 'The Last Tuniit'). The Tuniit poems again demonstrate Johnson's concerns with conservation, but like her language, they are never overplayed. A lost culture and people are apprehended through a more modern (but nevertheless period) apparatus and perspective, a movie viewed with 'the child in you shipwrecked / in a blinds-drawn classroom'. Western appropriation is summarised simply and tellingly by the Tuniit, the whalers 'not just whaling / for themselves, but for an animal so hungry / it could eat the world'.

The poems in 'Evanescence' skilfully articulate colour, light, air and memory, and their passing. Childhood glimmers in the consciousness of the adult, reprising the subject matter of 'Ties'. The memory of an ageing, unsympathetic neighbour is illustrated pithily: 'Stared at me sometimes with eyes like fried / eggs: but yellow where the white should be' ('The Woman Next Door'). 'Drowning in Air' uses the apparatus of the children's playground to draw the peculiar drowning of an asthma attack: 'each / hand-span of breath bent and stretching / for the next monkey bar in his lungs.' 'The Young Lady Practises Martyrdom' and 'Things to be Grateful For' round off the collection with touches of whimsy, even as they employ Christian symbolism.

In ‘Between the Lines’, Johnson writes: ‘childhood dazzles, bypasses / the naked. Eye’. But Johnson's eye, and ear, have captured more than enough to reward. Memory's snapshots and machinations, its random catalogues of our pasts, lie beautifully revealed.

Comments powered by CComment